Who Captures Liverpool Street? A Political Economy of Network Rail & ACME

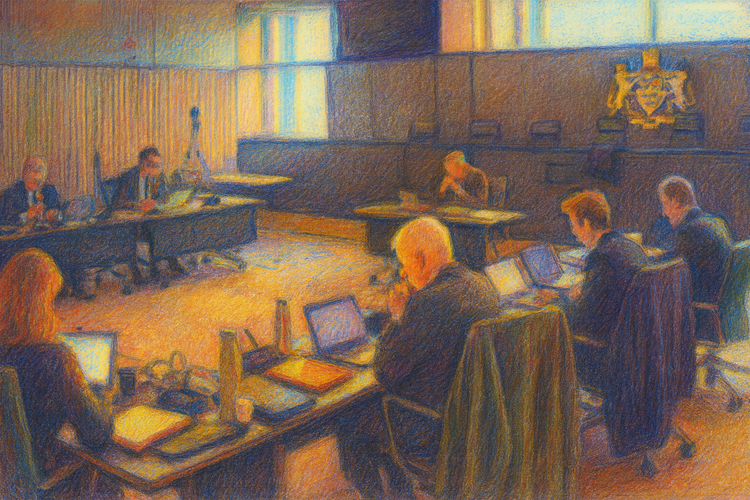

Liverpool Street Station’s redevelopment has now been approved, a 19–3 vote taken under conditions that made “public benefit” feel both decisive and strangely unmeasurable. In our previous report we showed how the hearing’s structure rationed democratic time, how key benefit claims shifted under questioning, and how the central justification, that station improvements require an office-led overbuild, was treated less as a proposition to test than as a constraint to accept. The result was a familiar modern bargain: public infrastructure “rescued” by commercial massing, with heritage harm and airspace capture folded into the price of entry.

This series begins where that article ends: beneath the theatre of planning, at the level of political economy. If “viability” is doing the governing work, narrowing the range of what can even be imagined, then the first civic task is to reconstruct the missing baseline and follow the value flows the committee was not required to see. We examine how Network Rail and ACME’s scheme converts a public transport asset into a development platform; how uncertainty is managed and leverage quietly traded away; and why the absence of a transparent, independently testable “station-first” minimum is not a technical gap but the hinge on which consent is manufactured.

Political Economy Part I

The Managed Uncertainty of “Public Benefit” and the Missing Baseline

They called it a once-in-a-generation upgrade. A gateway befitting a “Global City.” A “one-off opportunity.” But this is the language of inevitability: rhetoric that turns a political choice into a technical fact. The Liverpool Street Station scheme was sold as a necessary public investment that must be privately financed, and therefore must be office-led. Members were asked to accept the demolition of a listed station complex because the alternative, a station-first scheme with a minimum viable baseline, was treated as if it should not exist.

That is the first political economy fact: the baseline is missing by design.

The Newmark planning case states, explicitly, that the proposals were submitted on the basis that the redevelopment would be “entirely self-funded,” with the over-station office development and enhanced retail used to finance station works. The application form confirms the centre of gravity: a new building above 50 Liverpool Street rising to roughly 97.64m and 19 storeys, alongside a scheme cost “Over £100m.”

This is not just a design proposition. It is a financing structure. And financing structures make architecture.

1. The false bind: “accept massing, or accept failure”

The planning statement sets out the familiar sequence: Liverpool Street is “failing” as a station; passenger growth will overwhelm it; without major intervention there will be overcrowding, disruption, even closures. This story is not incidental. It is the moral pressure behind the deal. The scheme offers the City an escape from operational risk, but only by importing a second risk: demolition-led heritage harm, and the long-term transfer of value from public infrastructure into private real estate.

In plain terms: the public is asked to trade a public problem (capacity, accessibility, legibility) for a private solution (commercial development over a national transport asset). The argument is framed as pragmatic, even benevolent. But it is also strategic: once the station’s urgent needs are set on the table, the over-station offices are made to appear not as a choice, but as the only route to rescue.

This is the managed uncertainty of public benefit: the scheme makes the station crisis visible, while keeping the financial alternatives opaque.

2. The absent document: the station-first minimum baseline

A serious public decision requires comparison. Yet the applicant’s case leans on a single central proposition: that the scale of commercial development is linked to funding station works, and that not all feedback can be accommodated for “operational and viability reasons.” The problem is not that viability is mentioned; the problem is that the public is not shown the spectrum of viable options.

What is the smallest intervention that:

- makes the station step-free, coherent, and safe,

- delivers the necessary concourse capacity,

- and preserves the historic fabric to the greatest extent?

That is the baseline. Without it, “viability” becomes a political weapon: a word that closes debate rather than enabling it.

The application lists a long catalogue of station improvements, expanded concourse, additional lifts, escalators, new ticket hall arrangements, new entrances, better wayfinding, and it is perfectly possible to support those aims while refusing the claim that only an 88,013 sqm office deck can deliver them.

The City approved demolition and massing without first being shown what “station-first” looks like at minimum. That is not a small procedural omission; it is the hinge of the entire political economy.

3. Who captures the upside?

Liverpool Street Station is not a generic development plot. It is national infrastructure: a node where public investment, land value, and commuter necessity collide. Over the last generation, Britain has normalised a pattern: state assets and state-enabled land value are treated as a reservoir that can be tapped, packaged, and monetised. The station becomes a platform — literally — for private rent extraction.

The planning case is candid about the scale of the over-station component: circa 88,000 sq m GIA of offices, dressed with “Destination City” flourishes — roof garden, auditorium — the sweeteners that make a commercial envelope sound like civic culture. But the structure remains and the financial documents make it plainer than the rhetoric: station “improvement works” are costed at £419.58m, yet the modelling still reports a deficit even after the commercial components are counted; in the applicant’s own present-day outputs, station retail generates £197.5m of residual value while the office generates £44.2m. The public, then, is offered a constrained uplift, just enough to license the deal, while the market receives what the scheme is truly organised to produce: a new office monument above a national station in one of Europe’s most valuable commercial districts.

The crucial question is not “does the scheme provide benefits?” The question is: who owns the benefits, who controls them, and who takes the long-run surplus generated by building over a national station?

4. The public purse, treated loosely

In principle, a self-funded scheme sounds like fiscal prudence: no taxpayer subsidy, no direct public spending. But “self-funded” does not mean “public value protected.” It can mean the opposite: that the public pays indirectly, through the surrender of irreplaceable heritage, through the permanent dedication of airspace to private commercial use, and through the opportunity cost of not pursuing value capture for the public.

And here the City’s role matters. The planning system is not simply an approvals pipeline; it is the state’s value gate. When the City grants permission for large commercial massing over public infrastructure, it is not just allowing a building; it is allocating a future stream of rent and trading it for an immediate package of works.

By approving without demanding a station-first baseline, the City effectively accepted the applicant’s framing: that the only public interest is a functional station, and the only way to get it is to approve the commercial envelope.

That is an extraordinarily loose posture toward the public purse, not because the City writes a cheque, but because it signs away leverage.

5. The long build, the long lock-in

The phasing tells its own story. The application anticipates enabling works commencing in December 2028, with demolition and construction running from November 2029 to July 2036. This is not a quick fix. It is a multi-cycle urban commitment, during which the City will absorb disruption, risk, and cumulative impacts while the financial logic of the scheme remains embedded.

It is also why baseline matters even more: without an explicitly defined minimum station solution, the City cannot tell whether it has locked itself into necessary harm, or merely profitable harm.

6. What Part I concludes — and what Part II will do

Part I makes one central claim: this decision was staged as a technical inevitability when it was, in fact, a political choice about value, ownership, and the management of public assets. The applicant’s documents establish the logic clearly: station works plus an over-station office development presented as the means of funding them. The missing piece is the comparison that would have allowed the public and Members to evaluate that logic properly: a station-first minimum baseline, and transparent alternatives for paying for the works.

Part II follows the money more directly: the institutional roles and incentives (City of London Corporation, Network Rail, consultants, viability narratives), and the methods by which “public benefit” is asserted, quantified, and insulated from challenge — even as the scheme’s most irreversible costs (heritage demolition and airspace capture) are treated as collateral.

For now, the democratic requirement is no longer a pre-condition; it is a post-approval obligation: the City should publish the station-first minimum baseline that was never put before the public, disclose the viability assumptions relied upon to justify scale, and bind promised station outcomes to enforceable triggers and remedies across the build programme. Without that, “public benefit” remains what it was at the hearing: decisive in tone, and unmeasurable in fact.

Editorial Note

This article forms part of ConserveConnect.News’ ongoing public-interest coverage of the Liverpool Street Station redevelopment and is presented as independent political-economic analysis of the scheme promoted by Network Rail and designed by ACME.

Factual references are drawn from publicly available planning documents and related materials in the public domain, including the submitted application documentation and associated committee records where applicable. Interpretation, critique, and framing are the author’s own, offered in good faith as commentary on matters of significant public interest.

This commentary is published in accordance with the National Union of Journalists’ Code of Conduct and IPSO Editors’ Code principles of accuracy, fairness, and responsible journalism. Where the article refers to individuals or organisations, it does so for the purposes of scrutiny of public decision-making and the governance of public assets, not personal allegation.