Torquay Pavilion and the Duty of Conservation: A Test of National Will

Set against the sweeping backdrop of Tor Bay, the Torquay Pavilion is one of the great survivors of Edwardian seaside architecture—a jewel-box-like civic venue opened in 1912, rich with stained glass, ironwork, and optimism. Designed as a public pleasure pavilion, it once hosted concerts, exhibitions, and events that drew locals and tourists alike. But today, it lies shuttered and decaying, cordoned off after years of neglect and failed redevelopment plans. What should be a proud landmark is now an emblem of systemic failure.

The Pavilion’s plight has not gone unnoticed. In 2025, the Victorian Society included it in its Top Ten Most Endangered Buildings list, calling it "a classic example of a local authority failing in its responsibility to safeguard its own heritage assets." Its inclusion confirms what many in the community have long argued: the Pavilion is not just a local matter—it is a national test of whether we still value our architectural legacy.

This article argues that the conservation movement—professionals, campaigners, institutions, and the public—must come together in support of buildings like the Pavilion. It also offers a blunt warning: inaction is not neutral. It is a decision with lasting consequences. Letting this building die would represent a profound failure of ethics, governance, and civic imagination.

The Pavilion’s Cultural and Architectural Significance

The Torquay Pavilion was designed by Edwardian architect Edward Rogers and opened with great fanfare in 1912. It is richly ornamented in Baroque Revival style, complete with a central copper-domed roof, decorative iron balconies, and a rhythmic series of arched windows that once spilled light into a grand interior hall. It has been described by heritage campaigners as “a visual anchor of the seafront,” and rightly so. Its architecture celebrates public beauty, leisure, and shared space.

Conservation professionals assess such buildings by developing a Statement of Significance, a structured evaluation of a building’s historical, architectural, and communal values. These statements help determine what is worth preserving and how. The Pavilion scores highly on all counts: it is a rare Edwardian civic venue, one of few remaining on the south coast; it carries deep social value to generations of local people; and it forms part of Torbay’s wider seafront character.

Understanding Conservation Ethics: A Duty to Past and Future

Conservation is about more than saving old buildings—it is grounded in a framework of ethical responsibility. This framework includes principles such as honesty (respecting the truth of a building’s history), stewardship (caring for something that is held in trust for future generations), and minimal intervention (avoiding excessive changes that distort heritage value).

When local authorities neglect historic buildings in their care, they breach these ethical duties. As the Building Conservation Directory puts it: “Heritage conservation is fundamentally an ethical enterprise. It requires long-term thinking, humility in the face of history, and a commitment to public value.” To let the Pavilion decay while blaming delays or finances is not simply bureaucratic—it is morally negligent.

A Broader Pattern: Buildings at Risk Across the UK

The Pavilion is one of many buildings in danger. The Buildings at Risk (BaR) Register, maintained by groups such as SAVE Britain’s Heritage and Historic England, records dozens of significant historic sites facing neglect, insensitive development, or decay. Consider the following examples:

- Church of St. George in the East, Tower Hamlets – A rare surviving church designed by Nicholas Hawksmoor. Though rebuilt after WWII, it now suffers from extensive water ingress due to leaking roofs and poor maintenance of the flats added within its walls.

- Shire Hall, Chelmsford – A Grade II*-listed Georgian courthouse that served Essex for over 220 years, now disused since 2012 and facing slow deterioration despite local campaigns for reuse.

- Oasis Leisure Centre, Swindon – An iconic 1970s building with a 45-metre dome, associated with the eponymous band. Despite its architectural significance and cultural value, it faces demolition without clear preservation plans.

- The Lawns, University of Hull – Notable halls of residence built in the 1960s, now under threat despite being emblematic of post-war educational architecture.

- Wythenshawe Hall, Manchester – One of the last timber-framed manor houses in the region, damaged by fire and now struggling for restoration funding.

- Museum of London and Bastion House – A major post-war cultural complex designed by Powell & Moya, now at risk of demolition as part of a City of London redevelopment scheme, sparking national protest.

These buildings differ in style, scale, and use, but they share one thing: a lack of political will to see them properly conserved. They reflect a country drifting away from its own cultural inheritance.

What Can Be Done: Commissioning Care and Planning for Reuse

In heritage practice, the term commissioning care refers to the process of actively planning for the long-term upkeep and sustainable reuse of buildings—rather than waiting for crisis to strike. This involves expert surveys, conservation management plans, and public consultation. When done correctly, it can prevent decline and shape viable future uses.

For the Pavilion, a practical path forward would include:

- Stabilising the structure to halt further deterioration.

- Commissioning a conservation-led masterplan to assess feasible uses—community events, arts programming, mixed cultural-commercial use.

- Applying for emergency funding, including from the National Lottery Heritage Fund and Historic England’s High Streets Heritage Action Zones.

- Reasserting public ownership or bringing in a trust-based structure, ensuring future accountability.

Many towns have shown what’s possible. Margate’s Dreamland, Hastings Pier, and the Piece Hall in Halifax are all successful examples of heritage-led regeneration that create jobs, tourism, and community pride.

Time, Change and Adaptive Reuse

As conservation theorist John Earl has written, time is integral to the life of a building. Historic buildings don’t exist outside of history—they evolve with it. Conservation is not about freezing time but managing change sensitively. This is called adaptive reuse: finding new purposes that respect a building’s character while ensuring relevance.

For the Pavilion, this could mean creating a modern events space within the historic envelope, combining retail, performance, and exhibition functions. The dome, the ironwork, and the façade can all be restored while updating the interior for contemporary use. In the hands of skilled conservation architects, such a transformation is both respectful and economically viable.

Sustainable Conservation: Heritage as Climate Action

Conservation is often overlooked in climate debates, but the built environment is one of the UK’s largest carbon contributors. The demolition and rebuilding of structures waste what’s known as embodied carbon—the energy already invested in the original construction materials and methods.

The Pavilion, by being restored rather than demolished, would retain this embodied carbon. It would also support local trades, traditional crafts, and sustainable urban design. The Building Conservation Directory argues that sustainability must be measured not just in carbon, but in social cohesion, continuity of use, and the durability of traditional materials.

This is heritage conservation as environmental responsibility.

Guardianship and Accountability

The idea of guardianship in conservation refers to the responsibility held not just by owners, but by communities, governments, and professionals. It acknowledges that heritage belongs to everyone—and must be protected for future generations.

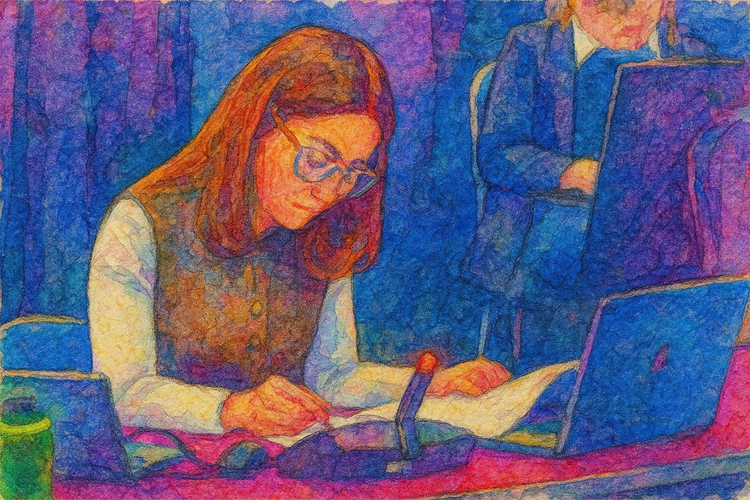

The current situation at Torquay Pavilion is a textbook case of failed guardianship. A local authority granted a long lease to a developer, failed to enforce planning conditions, and allowed an iconic public building to close. This is not just mismanagement—it’s a breach of the public trust.

The Victorian Society’s 2025 Endangered List is a clarion call. Without pressure from national institutions, journalists, conservation professionals, and the public, the Pavilion may continue to languish until restoration becomes impossible.

A Line in the Sand

The Torquay Pavilion is not an isolated case. It is a warning sign. A society that shrugs when a building like this fails is a society that has lost its cultural compass. When we allow places of shared beauty and memory to be discarded, we impoverish not just our towns, but our collective identity.

But the future is not yet written. The Pavilion can still be saved—if the conservation community speaks with one voice, if local and national government step up, and if we commit to a broader culture of care. This means action, not reports. It means funding, not apologies. And above all, it means choosing the future we want: one where our past still has a place in it.

To those with power: your silence is complicity. To the public: your voices matter. And to all of us: this is our moment to stand up for the places that shaped us.