The Great Housing Betrayal Already Happened in Brick Lane

When Aditya Chakrabortty exposed how Labour’s leaked housing memo judged success by whether “developers welcome the package strongly on the day,” he gave language to something East Londoners have felt for years. In neighbourhoods such as Brick Lane and Whitechapel, the policy of “developer confidence” has already rewritten the landscape — not only in bricks and leases, but in memory and belonging.

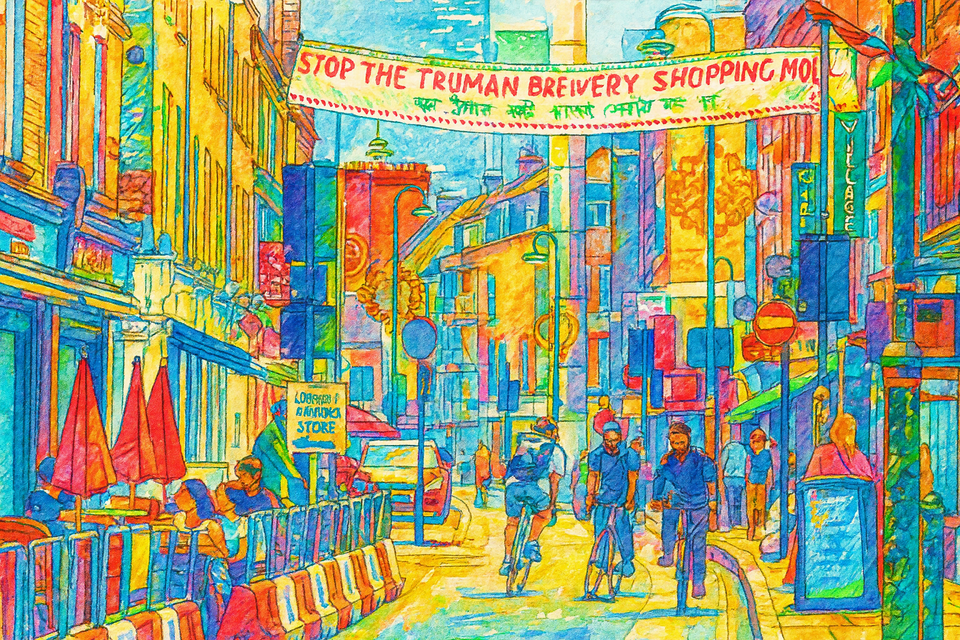

A Street That Defended Itself

Brick Lane’s story is inseparable from struggle. As Kaamil Ahmed reported in The Guardian (23 Aug 2025), the British-Bangladeshi community remembers when the street had to be defended physically from the far right. In the 1970s and 80s, young residents like Mohammed Abdul Sobhan took turns guarding street corners, fending off National Front attacks. “We can come out and stop them,” he recalled, “but they will come back two months later.” This was the architecture of self-defence: the community itself became the wall. The same civic courage that resisted open racism now confronts its financial descendant — the slow violence of economic exclusion. Each era’s aggressor changes its uniform: from the street-fighter to the spreadsheet, but the aim remains constant — to remove working-class life from the city’s centre.

The Two Forms of Continuity

In a living city, two forms of preservation reinforce each other. The first is the continuity of community cultures — the layered histories of work, migration, faith, and everyday exchange that make a district legible to its own residents. The second is the continuity of built fabric and public realm — the streets, workshops, market arcades, and façades that give those cultures physical coherence. To safeguard one without the other is meaningless. When culture is uprooted, architecture becomes hollow décor; when buildings are erased, memory loses its anchor. Together they form the civic commons — the shared inheritance through which citizens recognise themselves in their surroundings.

Raju Vaidyanathan’s 1980s photographs, published by Chitra Ramaswamy in The Guardian (6 Mar 2017), capture this symbiosis perfectly: schoolchildren outside Whitechapel Art Gallery; washing lines strung across Myrdle Street; a mosque that was once a synagogue that was once a Huguenot chapel. They reveal a continuum of adaptation — Huguenot silk-weavers, Jewish tailors, Bengali restaurateurs — all occupying the same modest terraces. Preservation, here, was not nostalgia but the living rhythm of accretion.

Across East London, redevelopment has treated both sides of this coin as expendable. Planning policy has reduced heritage to façade retention and community to marketing language. What is sold as “urban renewal” is, in practice, cultural erasure through capital displacement — a technocratic model in which financial yield substitutes for social purpose.

Brick Lane as Mirror

The Truman Brewery saga is the clearest example. Once a working industrial estate that evolved into a hub of artists, traders, and Bangladeshi businesses, it has been reimagined as a high-spec retail and office campus aimed at global tenants. Over 7,400 objections, cross-community alliances, and two rounds of hearings have not altered the underlying logic: replace social density with capital intensity.

Harriet Sherwood’s Observer report (19 Sept 2021) chronicled the moment when Tower Hamlets first approved the plan — a decision denounced as “a corporate intervention into the heart of a fiercely independent neighbourhood.” MP Apsana Begum warned that rising rents would “drive out” local independents; Fatima Rajina of Nijjor Manush called the scheme “the starting point of commercial redevelopment” that would harm “one of the poorest communities in the country.”

The Runnymede Trust’s Beyond Banglatown report warned that “the future of Bengali Brick Lane looks increasingly uncertain.” Those warnings proved prophetic. In July 2025, Tower Hamlets refused a revised masterplan on grounds of over-development, inadequate affordability, and heritage harm. The developers appealed — the issue now before a public inquiry.

Surrounding projects tell the same story:

- Whitechapel Bell Foundry (2019): Britain’s oldest factory converted into a boutique hotel despite national protest.

- 101–105 Whitechapel High Street Redevelopment (2024): demolition of historic frontage for a 17-storey tower behind a token façade.

- Woodseer Street infill schemes (2021–2023): smaller offices and short-lets gradually eroding the conservation-area grain.

Each replaces lived continuity with branded novelty. Each aligns with the pattern identified in ConserveConnect.News’ “Building New Towns, Letting Old Ones Die”: public neglect followed by speculative “rescue,” culminating in displacement disguised as progress.

Extraction as Policy

In ConserveConnect.News’ “The Billion-Pound Loss: Who Really Profits from London’s Redevelopment Boom”, we documented how billions of pounds in public value vanish annually through discounted land sales, relaxed Section 106 levies, and opaque “viability” accounting. The leaked Labour memo’s pledge to streamline obligations merely codifies that loss. This is not housing policy but financial engineering — an upward redistribution of wealth where community is the collateral. Every waived levy, every “flexibility” clause, represents another extraction of social capital into private balance sheets.

As Cédric Durand argues in Fictitious Capital (2017), financialisation converts future social value into present-day claims; cities become reservoirs of securitised expectation. Brick Lane’s redevelopment is exactly that: a promise of yield pre-sold to investors, redeemable only through the erasure of existing life.

Guy Standing, in The Corruption of Capitalism (2016), names this system the rentier economy — one where wealth flows not from production but from control of scarce assets. In East London the rentier is no longer the absentee landlord of the nineteenth century but the offshore fund monetising heritage through lease premiums and tourist cachet.

And Brett Christophers, in The New Enclosure (2019), traces the deeper genealogy: four decades of privatisation that stripped public land of democratic purpose. The Truman Brewery, sold in 1995 and now ring-fenced by private planning rights, is one small chapter in that national enclosure — the transformation of civic ground into financial territory.

Cultural and Material Consequences

The impact cannot be measured only in square metres. What is being dismantled is an entire ecosystem of interdependence — the Bengali cafés, print studios, vintage shops, and informal economies that sustained Brick Lane’s identity. The same forces that demolish façades also dissolve relationships. To walk those streets today is to sense a kind of civic anaemia: heritage maintained cosmetically while the life it once sheltered is priced out.

This is not nostalgia. It is the recognition that architecture is social infrastructure — that the pattern of streets and the pattern of lives are one and the same. When redevelopment breaks that link, it produces what Jane Jacobs called “a city designed for passing through, not for living in.” The glass and steel that rise in its place are monuments to absence.

A Politics of Replacement

Labour’s leaked memo exposes a governing assumption shared across parties: that growth equals construction and that construction, by definition, equals good. But growth measured in cranes and yields can coexist with decline measured in community. The East End has become the proving ground of a class intervention by architecture — the spatial enforcement of inequality under the guise of regeneration. Every new tower asserts a hierarchy of access: who may dwell, who must commute, who disappears.

Towards an Ethics of Continuity

Reversing this trend requires recognising that the preservation of culture and the preservation of place are not rival priorities but reciprocal duties.

Policy must bind them together through:

- Mandatory cultural-heritage impact assessments alongside environmental ones, treating social continuity as a planning consideration.

- Public ownership or long-lease stewardship of historic assets, ensuring adaptive reuse serves local enterprise rather than speculative resale.

- Transparent viability data and enforceable affordable-space quotas for artists, traders, and residents.

- Protection of informal public space — courtyards, arcades, pavements — where social life reproduces itself outside of consumption.

Such measures would turn “regeneration” from a euphemism for replacement into a framework for repair.

As Vaidyanathan’s photographs remind us, each wave of settlement in Brick Lane — Huguenot, Jewish, Bengali — left something tangible for the next. The moral test of planning is whether the next wave will build without erasing the last.

The Inquiry as Reckoning

As the 2025 Public Inquiry into the Truman Brewery appeal unfolds, it is more than a test of one development. It is a moral inquest into how Britain values its cities. The campaigners of Save Brick Lane argue not merely for conservation but for coherence — the right of a place to remain recognisable to those who made it. If the Inspector upholds that principle, it could mark a turning point: proof that planning can still serve memory as well as money.

Until then, the Great Housing Betrayal that Chakrabortty describes will remain visible in the very skyline — glass against brick, profit against people. To preserve either the buildings or the communities of Brick Lane, we must understand that they are the same structure seen from two sides of the same coin.