The Ayelsham Inquiry Day Three — The Arithmetic of Clearance: Viability and the Price of Peckham’s Future

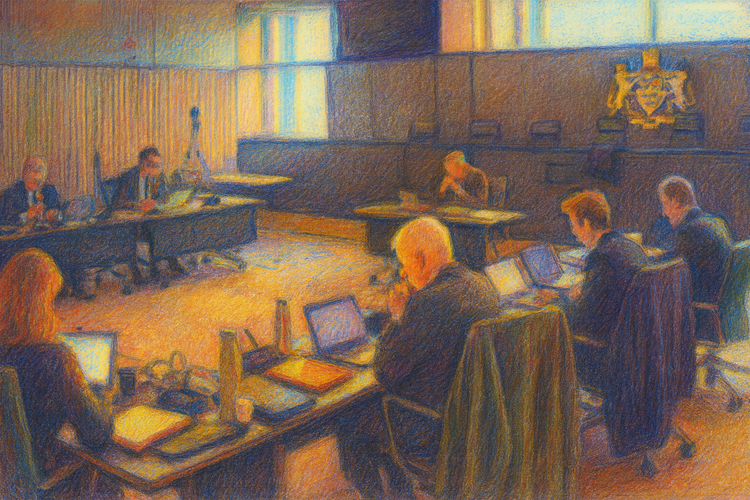

Prelude — The People Around the Table

By the third day of the Aylesham Centre Inquiry, the cast was familiar; what had changed was the script.

We were back in the same near-square, fluorescent-lit room in Southwark Council’s Tooley Street extension. Three walls were lined with desks; the fourth held rows of chairs for the public. The centre of the room was left open, a rectangle of carpet between the people who would decide Peckham’s future and those who would live with the consequences.

At the “front”, facing the room, sat Inspector Martin Shrigley, the state’s appointed listener, with a slim monitor and piles of paper arranged in front of him. To his right, along one wall, the Appellant’s team: Russell Harris KC flanked by Berkeley’s planners, viability consultants, and designers, their laptops open on colour-coded bundles. To the left, mirroring them, the London Borough of Southwark’s team, led by Richard Turney KC, with planning and heritage officers working from heavily annotated hard copies.

Directly opposite the Inspector, on the fourth side of the room, sat Aylesham Community Action (ACA). Their narrow table formed a strip of formal space in front of the public gallery: behind them, in tight rows, the traders, residents, faith leaders, and neighbours who had filled Day One with testimony. At ACA’s end of the table sat Hashi Mohamed, the community’s advocate — physically the furthest institutional figure from the Inspector, and in the Teams recording often outside the main camera frame. Clearly audible; rarely visible.

It is worth noting, without suggesting impropriety, that all three leading advocates in the room — Harris for Berkeley Homes, Turney for Southwark Council, and Mohamed for Aylesham Community Action — are members of the same barristers’ set, Landmark Chambers. At the Planning Bar this is entirely orthodox: each is independently instructed by different solicitors, owes duties to their own client, and operates behind chambers’ internal firewalls. Yet the image is hard to ignore. Three counsel, drawn from a single specialist set, articulate three competing versions of the “public interest”: one anchored in delivery and growth, one in policy integrity, and one in the right of a community to remain. The scene captures something of the contemporary planning state: not a crude conspiracy, but a highly professionalised system in which even conflict is organised through shared institutions.

Across Days One and Two these voices had traced out the moral and political contours of the scheme — need, heritage, regeneration. On Day Three, with the same people in the same seats, the Inquiry turned to the instrument that would decide which version of the future survives contact with the numbers: viability.

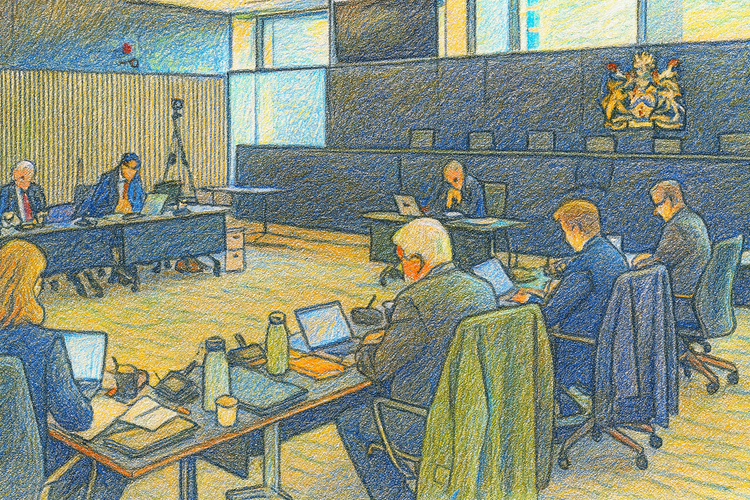

Prologue — The Room Where Numbers Decide

The Inquiry takes place in a near-square rectangular room in Southwark Council’s Tooley Street extension. Three walls are lined with tables; the fourth with rows of chairs for the public. The centre is left open: a neutral rectangle of blue carpet that gives everyone a line of sight to everyone else.

At the “front” of the room, the Inspector’s table faces directly across to ACA and the public behind them. To his right, the Berkeley team; to his left, Southwark. Behind ACA sits the gallery — the people whose lives are described in the documents arrayed around the perimeter.

There is no elevated bench, no jury box, no dramatic lighting. Just fluorescent strips, thin microphones, and a single wall-mounted screen that flickers on occasionally when a document is shared. Most of the time, each party works from its own copy of the bundles — printed, tabbed, annotated.

On Day Three, that quiet arrangement becomes part of the meaning. This is not the spectacle of planning; it is its machinery. Heads bent over spreadsheets. Page numbers called across the room. “Can we all turn to Appendix 1?” “If you look at the sensitivity testing…” The atmosphere is restrained, procedural, almost dull.

In that dullness lies its power. What is being decided here does not look dramatic — but it will determine whether the Aylesham Centre is demolished and rebuilt as a high-yield investment scheme, or remains in any recognisable relationship to the community that has used it for decades.

I. The Arithmetic of Necessity

The day’s centre of gravity is Nicholas Alston, Berkeley’s planning and viability witness. His role is to translate the scheme into numbers that can be presented as fact.

He begins with a line that is repeated often enough to feel like doctrine:

“Twelve per cent affordable housing is not a shortfall but the maximum reasonable contribution at this point in the cycle.”

The phrase carries two important moves. First, it certifies 12% as a ceiling rather than a floor. Second, it displaces responsibility: it is not Berkeley that wants 12%, it is “the cycle” that allows no more.

Russell Harris KC builds around that phrase. Turning to the viability appraisal, he leads Alston through its architecture:

- A profit margin in the region of 20% on cost.

- Finance costs set at conservative (i.e. high) rates.

- Build-cost contingencies layered on top.

- A Benchmark Land Value (BLV) below which “land will not transact”.

Once these elements are accepted as fixed, the rest of the model follows. If the Inspector is asked to respect them, then 12% affordable housing ceases to be a choice. It becomes an outcome.

At this point, Southwark’s counsel, Richard Turney KC, shifts the angle. He reminds the room that the Southwark Plan’s 35% affordable housing benchmark was tested through borough-wide evidence. It is not wishful thinking but a viability-tested policy. To accept 12% as “maximum reasonable” is to accept that viability has quietly re-written the plan.

Turney sums it up in a single sentence:

“The gap here is not physical but financial — an artefact of how return is defined.”

What appears as necessity is, in truth, engineering.

From the ACA table, Hashi Mohamed names the social cost of that engineering:

“You call it deliverability; the community experiences it as withdrawal.”

Withdrawal of affordable homes.

Withdrawal of secure tenure.

Withdrawal of the right to stay.

Aalbers: When Profit Is Fixed and Need Is Flexible

This is exactly the dynamic described by Manuel Aalbers, the scholar of housing financialisation. In a financialised system, he argues, profit is treated as fixed; social need is treated as adjustable. The spreadsheet is not a neutral test. It is a device for ensuring that the developer’s required return is maintained and any shortfall is absorbed by reducing affordable housing or community benefit.

The Aylesham model is a textbook instance. Developer profit is immovable; affordable housing is the variable. The result is presented as “maximum reasonable” — as though the outcome were natural rather than constructed.

II. Profit as Public Good

As the morning progresses, the argument moves from “what is possible” to “what is responsible.”

Harris puts a simple proposition to Alston:

“A development that cannot be funded cannot be delivered, correct?”

“Correct.”

The implication is clear: insisting on more affordable housing is not only unrealistic; it is irresponsible. It risks turning a “deliverable” scheme into one that cannot proceed. Profit, in this telling, is not private gain but a requirement for the public interest.

Turney challenges the inner workings of that claim. He presses Alston on specific assumptions:

- Are the build costs set at the highest plausible level?

- Are finance rates padded beyond what is actually expected?

- Is supermarket re-provision treated as a pure cost, rather than an income-generating asset?

When he asks whether certain figures are not in fact hypothetical, Alston replies that they are “prudent”. Turney asks the obvious follow-up:

“Prudent for whom?”

It is a small question with a large answer. The prudence in this model is prudence for capital: a safety net for investors, not for residents.

From ACA’s side, Mohamed articulates what is at stake:

“When profit is fixed and housing need is flexible, who is the system protecting?”

Christophers: The Rentier Logic in the Room

Here, Brett Christophers’ work on rentier capitalism becomes unavoidable. He argues that the contemporary British state has been refashioned to secure revenue streams to asset-owners, especially landowners and large developers. What appears as “sound viability practice” is, in his analysis, a legal-institutional system designed to ensure that certain forms of income are never put at risk.

In that light, the 20% profit margin in the Aylesham model is not just a business target; it is an entitlement. The viability appraisal treats it as a non-negotiable cost of doing public business. The effect is to shift risk downward: away from the investor and onto the community, whose claims — on housing, tenure, continuity — become the balancing items.

On Day Three, this shift happened quietly, line by line, as the model was walked through. Every time “deliverability” was invoked, what was really being defended was return.

III. The Rentier City: Benchmark Land Value

The next layer of the model is Benchmark Land Value — the figure that sits beneath all others.

Alston defines it in the language of standard practice:

“Benchmark land value represents the price below which the land will not transact.”

On its face, this sounds simply descriptive: an observation about the market. But as Turney’s questions make clear, BLV does something much more consequential.

He puts it to Alston that:

- The BLV is derived from market comparables already uplifted by speculative expectations.

- Those comparables are themselves shaped by the kind of high-yield redevelopment now under consideration.

- Once translated into the viability model, BLV becomes a floor that the scheme may not breach.

In other words, the model assumes the very uplift the Inquiry is meant to scrutinise.

Mohamed presses the same point in plain language:

“The land value you rely on already absorbs the expectation of redevelopment, doesn’t it?”

Alston maintains that the approach reflects “industry guidance”. He does not dispute the logic itself.

Christophers Again: The State as Guarantor

For Christophers, this is the rentier state at work: landowners’ expectations are translated into baselines that public decision-making must respect. Once BLV is treated as sacrosanct, everything that conflicts with it becomes negotiable — including affordable housing and community stability.

The result is that planning does not mediate between landowner interests and public interests. It organises public interests around the landowner’s minimum acceptable return.

IV. Creative Destruction in Numbers

As the afternoon wears on, the conversation circles around a phrase that appears repeatedly in Alston’s evidence: some options “would not come forward”.

Asked about scenarios with higher affordable housing — 20%, say, or more social rent — Alston confirms that such variants would render the scheme “undeliverable” and would “not come forward”.

Behind this apparently neutral language lies the engine that David Harvey has spent a lifetime describing.

For Harvey, capitalism must periodically engage in “creative destruction”: tearing down existing built environments that no longer yield enough return, and replacing them with configurations that can absorb surplus capital. The Aylesham Centre is a textbook candidate: a functioning but low-yield asset in an area now primed for higher-value redevelopment.

The viability model operationalises this logic:

- The existing centre is treated as an “underperforming asset”.

- The current pattern of traders and uses is framed as “inefficient” relative to potential.

- Demolition becomes the precondition for “unlocking” land value.

- Redevelopment at higher densities becomes the solution to capital’s need for a new outlet.

Turney asks whether the model takes account of the social value of the current use — the independent shops, the informal economies, the role of the centre in Peckham’s everyday life.

Alston answers, with disarming simplicity:

“Those are not viability inputs.”

Not viability inputs.

If something is not an input, it will never shape the output.

Its loss can be acknowledged in words, but not in numbers.

Mohamed crystallises the logic:

“If harm can always be outweighed in the balance, then nothing is safe.”

On Day Three, harm is not prevented; it is priced. Once priced, it can be outweighed. Once outweighed, it can be justified. Once justified, it can be enacted.

Harvey would recognise this instantly. It is creative destruction not as metaphor, but as arithmetic.

V. The Closure of Spatial Possibility

By late afternoon, the cumulative effect of the evidence is not simply to justify the Aylesham scheme, but to close off alternatives.

The viability appraisal does more than calculate. It prescribes. In its cells and formulas, it encodes a single future:

- one in which the Aylesham Centre is demolished,

- one in which 867 units are built at a particular density and mix,

- one in which 12% of those units are “affordable”,

- one in which Community Land Trust housing disappears,

- one in which retail floorspace shrinks and is “rationalised”,

- one in which the people currently trading on the site have no protected route back.

There is no column for “retain and retrofit”, no scenario for CLT-led partnership, no modelled option that weighs a different balance of return and social protection. In that sense, the spreadsheet does what Doreen Massey warned of: it reduces a place rich in overlapping “stories-so-far” to a single authorised trajectory.

Loïc Wacquant offers a name for this mode of operation: bureaucratic dispossession. Inequality is enforced not through overt force, but through procedures that look neutral. Here, viability is the key procedure:

- It recognises only that which can be priced.

- It treats investor security as prudence.

- It frames social losses as external to the model.

What is politically contested becomes procedurally settled. What might once have been a debate — about who Peckham is for, what regeneration should mean, how risk and reward should be shared — is converted into a technical dispute over “inputs” and “assumptions”.

By the time the Inspector calls an end to the day’s session, the limits of the imaginable have been quietly reset. The Aylesham Centre has been translated from a living complex of traders, shoppers, congregations and memories into a line of cells in a viability appraisal, and from there into a single question:

Does this scheme meet the required level of return?

Everything else — heritage, equity, belonging — has been relegated to secondary status.

VI. A Brief Guide to the Theory Behind Day Three

The language used in the Inquiry — viability, deliverability, benchmark land value — can sound technical and dry. But as the exchanges on Day Three show, it is saturated with politics. A short theoretical map helps to make this visible:

- David Harvey

Shows how capitalism repeatedly destroys and rebuilds parts of the city to keep capital flowing. Demolition is not a failure of planning but a feature of the system. - Brett Christophers

Explains how the British state now operates as a guarantor of returns to landowners and asset-holders. Benchmark Land Value is a legal form of that guarantee. - Manuel Aalbers

Describes the financialisation of housing. In this system, profit margins are fixed and treated as necessity; social provisions like affordability are treated as flexible extras. - Doreen Massey

Argues that places are multi-layered constellations of histories and futures. Viability flattens them into a single financial horizon — the one compatible with investor expectations. - Loïc Wacquant

Shows how inequality is enforced through bureaucratic devices that appear neutral. Viability assessments are a prime example: they depoliticise dispossession by framing it as a technical result. - Sharon Zukin

Reminds us that institutions which appear apolitical — panels, quangos, appraisals — often serve as the infrastructure of market-led transformation. Viability is such an institution in numeric form.

These thinkers are not a digression from the Inquiry; they are its unwritten glossary. Their work allows us to name what would otherwise remain implicit: that viability is an instrument of clearance and a language in which displacement speaks as “prudence”.

Coda — The Price of the Future

Across the first three days of the Aylesham Inquiry, a pattern has emerged.

- Day One framed regeneration as necessity — a response to crisis, a duty to deliver homes.

- Day Two wrapped that necessity in a moral script — heritage, sensitivity, the rhetoric of “repairing the grain”.

- Day Three exposed the engine — a viability model that translates that moral and political script into a single arithmetic of clearance.

In that arithmetic:

- Profit is fixed; need is flexible.

- Land value is sacrosanct; community value is residual.

- Harm is not prevented; it is priced.

- Displacement is not named; it is assumed.

The question left hanging at the end of Day Three is not a numerical one. It is the one Mohamed implied, and which planning law struggles to express:

If viability decides who may remain in Peckham, what becomes of the idea that planning serves the public interest?

Day Four will turn directly to equalities and displacement. The numbers will remain in the background. The people they implicate will step forward.

Editorial Note

This report is a fair and accurate account of open proceedings at the Aylesham Centre Public Inquiry (Day 3) and is protected by qualified privilege under Schedule 1 of the Defamation Act 1996. Commentary and interpretation reflect the author’s analysis, written in accordance with NUJ and IPSO standards for fair, accurate, and responsible public-interest reporting. Quotations are drawn from the official transcript and submitted Inquiry documents and are reproduced within the context of fair reporting and public record.

Index

Critical theorists referenced

- David Harvey

Harvey, D. (2006) The Limits to Capital (new ed.). London: Verso.

Used in the article for the idea of the “dialectic of creative destruction” – capital periodically demolishes and rebuilds the urban fabric to overcome barriers to accumulation. - Brett Christophers

Christophers, B. (2018) The New Enclosure: The Appropriation of Public Land in Neoliberal Britain. London: Verso.

Christophers, B. (2020) Rentier Capitalism: Who Owns the Economy, and Who Pays for It? London: Verso.

Drawn on for the concept of the rentier state and the way planning and viability work to secure income streams for landowners via mechanisms such as Benchmark Land Value. - Manuel B. Aalbers

Aalbers, M. B. (2016) The Financialization of Housing: A Political Economy Approach. London: Routledge.

Used for the argument that in a financialised housing system profit is fixed and affordability is the adjustable variable, with viability models calibrated to protect investor returns. - Doreen Massey

Massey, D. (2005) For Space. London: Sage.

Cited for the idea of space as a “simultaneity of stories-so-far” and for the critique of how planning and viability close down spatial futures by privileging a single, economised trajectory. - Loïc Wacquant

Wacquant, L. (2009) Punishing the Poor: The Neoliberal Government of Social Insecurity. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Also drawing on later essays on bureaucracy and inequality. Used for the notion of “bureaucratic dispossession” – how neutral-seeming procedures (formats, formulas, protocols) depoliticise and administer displacement. - Sharon Zukin

Zukin, S. (2010) Naked City: The Death and Life of Authentic Urban Places. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Referenced for her analysis of arm’s-length authorities and expert bodies that appear apolitical while enabling market-led transformation, a frame applied here to viability practice and to the institutional setting of the inquiry.

Core inquiry documents and planning sources cited / relied on (Day 3 focus)

(Document numbers follow the Aylesham Centre Core Documents Index, 30 October 2025.)

- AC15 – Aylesham Centre Financial Viability Assessment

CD1 – Planning Application Documents

1.23 AC15 Aylesham Centre Financial Viability Assessment

1.24 AC15.1 Aylesham Centre Financial Viability Assessment Executive Summary

Forms the backbone of the 12% affordable housing claim and the 17–20% profit assumption discussed on Day 3. - Appellant Viability Proofs

8.09 Pascal Levine – Viability Proof of Evidence

8.19 Pascal Levine – Viability Proof of Evidence Summary

8.25 Pascal Levine – Rebuttal Proof on Viability

Technical evidence underpinning the appellant’s viability position and profit / BLV assumptions referred to in the article. - Appellant Planning Proofs (context for viability narrative)

8.07-0 Nicholas Alston – Planning Proof of Evidence

8.17 Nicholas Alston – Planning Proof of Evidence Summary

8.24 Nicholas Alston – Rebuttal Proof on Planning

Used where the article quotes or paraphrases Alston’s characterisation of “maximum reasonable contribution” and deliverability. - ACA Affordable Housing / Viability Evidence

8.16-1 George Venning – Affordable Housing Proof of Evidence (including Summary)

8.16-2 George Venning – Affordable Housing Proof of Evidence Appendices

Drawn on for the critique of viability assumptions (finance costs, debt ratios, treatment of supermarket re-provision) and the reframing of viability as discretionary arithmetic. - Development Plan and Site Allocation (NSP 74)

4.02 The Southwark Plan 2019–2036 (2022)

6.13-1 Peckham and Nunhead Area Action Plan (2014) and associated appendices

(The Aylesham site allocation NSP 74 and its 35% affordable housing benchmark, CLT expectation and circa-850 unit capacity sit within these documents.) - Other referenced core documents (design / local economy context)

2.52 Nimtim Architects, Historic Character Analysis

2.53 Jas Bhalla Architects, Understanding Peckham’s Local Economy (Sept 2023)

Cited in Day 3 exchanges and used in the article to contextualise how local architectural and economic studies described the Aylesham Centre and its impact. - Core procedural material

12.04 Appellant – Opening Statement

12.05 LBS – Opening Statement

12.06 ACA – Opening Statement

Provide the three competing framings of public interest (delivery, policy compliance, community right to remain) that the article tracks across Days 1–3. - Transcript

Aylesham Inquiry Day 3 – Verbatim Transcript (Hearing day file)

Primary source for direct quotations and exchanges reproduced in the article (Alston’s evidence, cross-examination by Harris, Turney, and Mohamed, and references to NSP 74 and the bus station).