The Ayelsham Inquiry Day Four — Maximum Reasonable: Housing Need, Viability and Who Gets to Stay in Peckham

Prologue — Geometry of a Housing Crisis

As the Aylesham Centre Inquiry approaches midway, a pattern has begun to emerge — not all at once, but in distinct movements, each adding a new layer to the story of what “regeneration” now means in Peckham. Day One staged the clash of stories: Berkeley’s “wasteland backland” against the community’s “living, multicultural high-street economy,” with the Council caught in the middle trying to defend a plan that was already a compromise. Day Two put heritage on the stand and showed how guidance designed to restrain harm could be inverted to license it. Day Three pulled back the casing and revealed how those narratives and policies are compressed into a spreadsheet that decides how much of Peckham can survive redevelopment. Day Four returns us to the same room, the same faces, but with a sharper question: what that arithmetic actually means for who gets to live here, and on what terms.

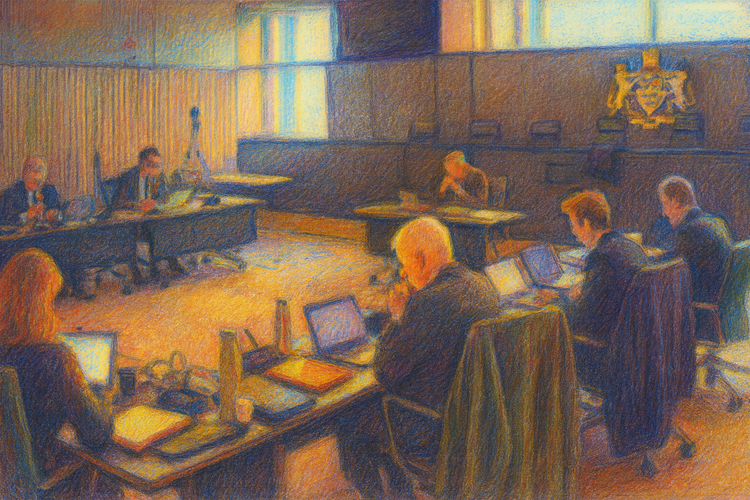

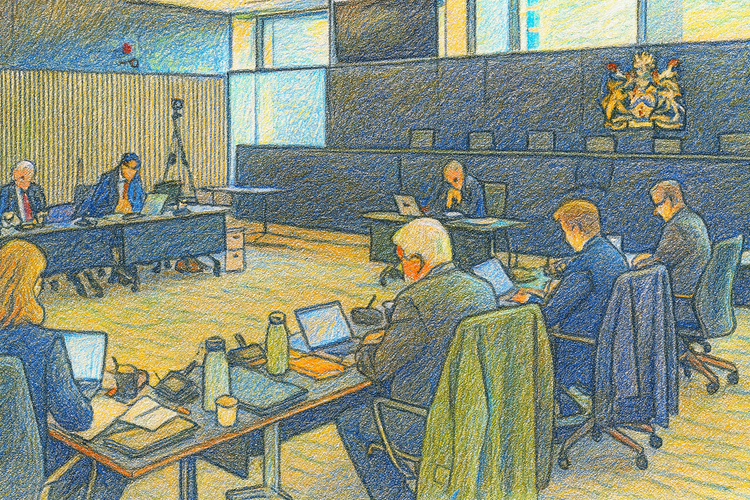

We are back in the near-square chamber of Southwark Council’s Tooley Street extension. Four sides, four lines of sight, four versions of the “public interest.” At the front sits Inspector Martin Shrigley, slightly raised behind a shallow desk, papers and screen angled towards him. To his right, along one wall, the Appellant’s table: Russell Harris KC, flanked by Berkeley Homes’ planning, design, and viability team, working from colour-tabbed bundles and open laptops. To his left, mirroring them, the London Borough of Southwark: Richard Turney KC with planning and heritage officers, the Southwark Plan and its evidence base spread across the desk in front.

Directly opposite the Inspector, on the far side of the room, sits Aylesham Community Action. Their narrow table stands between the inquiry and the public seating: behind them, in close rows, the traders, residents, faith leaders and neighbours who filled Day One with testimony. At the middle of that table is Hashi Mohamed of Southwark Law Centre, ACA’s advocate — physically the furthest institutional figure from the Inspector, but closest to the people in the gallery. In the Video recording he often falls outside the main frame: clearly heard, less often seen.

All three leading advocates – Harris for Berkeley Homes, Turney for Southwark Council, and Mohamed for ACA – are members of Landmark Chambers. In planning circles this is entirely orthodox: each is independently instructed by different solicitors, with strict duties to their own client and internal firewalls governing conflicts. But the optics are instructive. Three counsel from the same specialist set articulate three incompatible versions of the public interest: regeneration as delivery and growth; regeneration as policy integrity; regeneration as the right of an existing community to remain. Even conflict, here, is organised through shared institutions.

Act I — From Heritage Balance to Housing Arithmetic

The day begins in the shadow of the previous sessions. Inspector Shrigley reminds the room that they are “picking up where we left off yesterday” — in the initial cross-examination of Mr Eldridge, the Appellant’s heritage and townscape witness. The conversation is no longer about the Aylesham Centre as a physical object. It is about the way harm is counted, discounted, and ultimately normalised.

Turney’s questioning circles a narrow but crucial point: when Eldridge assessed the impact of the scheme at application stage, he did so using what lawyers now shorthand as the Bramshill/Stonehenge “internal balance” — folding both harm and benefit into a single professional judgment, rather than clearly separating the extent of heritage harm from the later planning balance. Eldridge confirms that this is indeed what he did, and that the conclusion in his Heritage Impact Assessment — that “on balance” there is no harm to the conservation area’s significance — is the same conclusion he advances to the Inquiry.

It is a small exchange on paper, but it exposes the logic that has been running beneath the first three days. If the existing Aylesham Centre is treated as an almost pure detractor and the new scheme as an almost pure improvement, then any loss of original roofline, scale, or grain can be absorbed into the category of “less than substantial harm” or, in Eldridge’s reading, no harm at all. The internal balance becomes a device for pre-authorising demolition: by embedding the planning judgment inside the heritage assessment, the later weighing of “public benefits” over “harm” is quietly short-circuited.

Seen through David Harvey’s lens, this is the cultural front end of creative destruction. Capital needs the existing built environment to appear obsolete — aesthetically, functionally, even morally — so that its replacement can be framed as renewal rather than clearance. Heritage consultants become translators of this necessity: their job, under pressure of policy and precedent, is to demonstrate that what already exists is so compromised that only radical intervention can “repair” it.

By the time Eldridge is released from the witness seat, the script is set. The Aylesham Centre is established in the inquiry’s official language as a “low-quality” post-modern monoculture; the proposed towers are positioned as the legitimate heirs to Rye Lane’s historic grain. The dialectic is complete: one term rendered unworthy, the other endowed with the authority to replace it.

What the morning session quietly accomplishes is a clearing of conceptual space. With the heritage debate compressed into “no harm on balance,” the afternoon is free to focus on what appears, at first, to be a different terrain: housing need, tenure mix, and viability. In reality, it is the same story told in another key — the story of how London’s planning system translates lived places into investment opportunities and then back into the language of public interest.

Act II — “180 Percent of What We Don’t Need”: Venning’s Three Themes

After lunch, the Inquiry returns to order and Mohamed calls George Venning — director of an affordable-housing consultancy and long-term local resident, introduced via a curriculum vitae that bridges professional expertise and lived knowledge of Peckham and Camberwell. Where previous witnesses arrived as representatives of institutions, Venning arrives as something more unsettling: a technician of the very system he is criticising.

Mohamed invites him to set out the “main planks” of his evidence. Venning offers three:

- the misalignment between the housing that is needed and the housing that is being proposed;

- the way viability conventions are being applied to lock in that misalignment; and

- the gap between Berkeley’s internal sense of viability and the “standardised” deficit presented to the planning system.

He begins not with sentiment but with numbers. Drawing on the Southwark Strategic Housing Market Assessment, he explains that the borough’s evidence base identifies an annual requirement of 2,932 homes in total, of which 2,077 are affordable — leaving roughly 850 open-market homes as the implied annual need. When those figures are translated into the Southwark Plan’s housing target and affordable-housing policies, the result is what Councillor Livingston once described as the “golden thread”: a deliberate decision to accept a large oversupply of market housing as the price of securing as much affordable housing as possible.

On Venning’s reading, the Plan effectively envisions delivering around 180 percent of the open-market homes required, while meeting only about 40 percent of affordable need. The community, in other words, has already agreed — through the adoption of the Plan — to tolerate more change, more density, and more speculative investment than it strictly “needs,” in the hope that this will cross-subsidise genuinely affordable homes.

“But on this site,” Venning argues, “that bargain has broken down.” Instead of 35 percent affordable housing, as tested when the site allocation was made, the Aylesham scheme now offers 12 percent by habitable room — 77 homes in total, only 50 of them for social rent. The promised Community Land Trust tenure, designed to experiment away from what he calls “a broken model” of shared ownership that leaves households paying rent on 70–80 percent of their home deep into retirement, has disappeared altogether.

Here the language of Brett Christophers and Manuel Aalbers — rentier capitalism, assetisation, financialisation of housing — comes into view without being named. The scheme’s viability is calculated not against the need profile of Peckham, but against the investment horizon of a PLC whose Land and Development Director has told councillors that Berkeley simply “does not proceed with schemes that it does not consider to be financially viable” on its own internal metrics.

Venning’s point is disarmingly simple: if the development plan already embodies a hard-headed compromise — “a willingness to accept a degree of harm” in return for meaningful affordable housing — then a proposal that delivers far less affordable housing while locking in the same or greater level of harm cannot plausibly be described as plan-compliant. The numbers do not merely fall short; they invert the bargain on which the Plan was sold.

Act III — Molior, Tall Buildings, and the Collapse of “Normal” Demand

The second movement of Venning’s evidence introduces a document that should, in principle, be entirely comfortable for a market-led inquiry: the Molior Q3 2025 report on residential development in London, already in the core documents in its Q2 form and now updated.

He summarises its key finding: across London, in schemes of 20 or more private homes, there were 5,933 new-home sales between Q1 and Q3 of 2025, but “sales to individuals are virtually non-existent” at prices up to £600 per square foot — the level at which “most London owner-occupiers can buy.” In other words, the Molior data describes “a collapse in demand for open-market housing” at precisely the price points that a local Peckham buyer might conceivably afford, while the Aylesham scheme is modelled on assumed sales values of £860 per square foot.

Underneath, a Venn diagram in the report identifies which planning permissions are “most likely to be built.” Height is the problem: Molior suggests that, in current conditions, development below £650 per square foot is generally unprofitable once costs are factored in, and that costs are “incredibly high where buildings are high” — above 18 metres, roughly six storeys. The Aylesham scheme, with its cluster of tall buildings and elevated build costs, lands squarely in this danger zone.

For Venning, the inference is twofold:

- First, that the case for oversupplying market housing as the necessary route to affordable provision is breaking down in real time. Investors are retreating from the very market segment (tall, high-value new build) on which schemes like Aylesham depend.

- Second, that reducing affordable housing from 35 to 12 percent in order to “improve viability” actually worsens the structural problem: it leaves a larger volume of expensive market homes to be absorbed by a shrinking pool of buyers.

This is Harvey’s periodic “switching” of capital into the built environment seen in granular form. When the cycle turns and the returns falter, the system discovers that the city has been remade not for residents but for a class of investors who can quietly withdraw. Peckham is left with the risk — the towers, the debt, the displacement — while the promised benefits evaporate into market sentiment.

Act IV — Plan-Led Worlds and the Politics of Deference

When Venning finishes his direct evidence, Harris stands to cross-examine. He does so not by disputing the Molior graphs or the SHMA percentages — indeed, he accepts much of the descriptive material — but by returning to the language that stabilises the planning system: this is a “plan-led world.”

Harris walks Venning through London Plan policy H5 and the “threshold approach” to affordable housing, then through the Affordable Housing and Viability SPG. If an application does not meet the fast-track threshold, he reminds the Inquiry, the borough’s job is to “scrutinise the viability information” and secure the maximum reasonable amount of affordable housing in line with the methodology. Venning agrees that the London Plan is not out of date and that full weight should be given to it.

From there, Harris turns to the Southwark committee report, which records that when the scheme was first submitted at 35 percent affordable housing, both the developer’s Financial Viability Assessment and the Council’s independent assessor (BPS) agreed that even zero affordable housing would technically be the “maximum viable” position. The current offer of 12 percent thus “exceeds the maximum viable affordable housing.” BPS, Harris stresses, is “no pushover”: a consultant who works only for local authorities and whose professional identity is built on challenging developers’ assumptions.

The point of the cross-examination is not simply to defend the numbers; it is to reassert the authority of process. If the London Plan says H5 is the framework, if the Southwark Plan adopts that framework, if BPS and Berkeley have agreed a deficit of £70 million even at 0 percent affordable housing, then — Harris implies — Venning’s wider critique may be morally compelling but is procedurally irrelevant. The Inspector must decide within the architecture of the policies, not outside it.

Venning does not contest the letter of that architecture; instead, he keeps returning to its consequences. Southwark, he notes, is a borough where the average house price is 12.5 times average income, compared with 8.3 times nationally; where social rented housing accounts for over 40 percent of Peckham’s stock; and where 93 percent of local residents need some form of subsidised housing. In that context, to present an 88-percent private, high-value scheme as the “maximum reasonable contribution” is not neutrality — it is taking sides, even if the system pretends otherwise.

This is where Loïc Wacquant’s work on territorial stigmatisation and Doreen Massey’s insistence that space is “the product of interrelations” become useful. Peckham is not a blank canvas on which London Plan policies are neatly applied; it is a dense web of social relations, survival strategies, and histories of racialised displacement. A “plan-led world” that refuses to see those relations except through ratios and thresholds is not neutral. It is structured to privilege certain kinds of knowledge — financial, legal, technical — and to marginalise others.

By the close of Day Four, the shape of the argument is clear. Heritage has been disciplined into “no harm on balance.” Housing need has been translated into a tradeable variable in a viability model. And the inquiry itself — with its deference to plan-led orthodoxy — has become the stage on which this transformation is narrated as public interest.

Coda — What Counts, and Who Doesn’t

By the close of Day Four, the Inquiry has drawn its own map of what matters.

We have heard that the Aylesham Centre is a “negative element,” that its demolition will “unlock” a major housing opportunity; that 12 percent affordable housing is not a shortfall but the “maximum reasonable contribution”; that benchmark land value and a 20 percent profit margin are prudence, while Community Land Trust housing and local traders are variables; that views from the Bussey rooftop and Peckham Levels can be obscured so long as a different public enjoys a different view from a different terrace; that Peckham has a “distinct feel,” but that the people who give it that feel fall outside the scope of expert evidence.

Across the first four days, a pattern has hardened.

- Day One staged the narratives: regeneration as growth, regeneration as policy, regeneration as survival.

- Day Two showed how heritage policy can be turned inward, its own language used to authorise the harms it was written to prevent.

- Day Three exposed the engine: a viability model that translates moral and political choices into a single arithmetic of clearance.

- Day Four revealed what happens when lived need tries to speak back in that language, and finds itself treated as an interesting but optional commentary.

In David Harvey’s terms, we are watching creative destruction in slow motion: a working urban fabric is reclassified as failure so that its replacement can be sold as cure. Brett Christophers and Manuel Aalbers help name the underlying transaction: planning becomes a delivery mechanism for rentier income streams, housing a vehicle for financial return. Doreen Massey reminds us that what is being closed down is not just a set of buildings but a set of possible futures. Loïc Wacquant shows how all of this is administered through procedures that look neutral — “maximum reasonable,” “plan-led,” “less than substantial harm” — even as they depoliticise dispossession.

The Inquiry is not blind to any of this. It hears about overcrowding in social rented flats, about the impossibility of buying in Peckham on ordinary incomes, about the long waiting lists and the fragility of local businesses. It records those facts in the transcript, then files them under “context.” What carries decisive weight, in the end, are the documents that can be aligned with the apparatus: the London Plan, the Southwark Plan, the Financial Viability Assessment, the expert proofs. The lives described by Venning, Mohamed, and the residents who spoke on Day One hover around the edges of those texts like a watermark.

This is the quiet drama of Day Four. No one says outright that the people who made Peckham what it is are expendable. The planning system never uses that language. Instead, it speaks of “trade-offs,” “balances,” “regeneration,” “optimising capacity.” It talks about numbers that must be hit, deficits that must be closed, benchmarks that must be met. It talks, as Harris did, of a “plan-led world.”

What it rarely acknowledges is that this world is already tilted. The plans themselves are the product of earlier compromises; the viability tests reflect earlier victories for capital over need. By the time a community finds itself in a room like this, the terms on which its future can be argued have already been heavily pre-edited.

And yet, something else is happening in that room as well. Each time Venning forces the Inquiry to sit with the mismatch between what Peckham needs and what Aylesham will deliver; each time Mohamed asks whether “maximum reasonable” means maximum for residents or maximum for Berkeley; each time a resident in the gallery nods or sighs or stares at the floor — the official record thickens with a counter-history. It is not enough, on its own, to bend the outcome. But it is enough to make clear that if this scheme is approved, it is not because there was no alternative. It is because an alternative was ruled out by design.

The days that follow will move on to equalities and displacement, to planning orthodoxy and closing submissions. The engine identified on Day Three will continue to hum quietly in the background. Day Four matters because it shows us who is strapped to it — and what the system is willing to write off as collateral in the name of regeneration.

Editorial Note

This report is a fair and accurate account of open proceedings at the Aylesham Centre Public Inquiry (Day 4) and is protected by qualified privilege under Schedule 1 of the Defamation Act 1996. Commentary and interpretation reflect the author’s analysis, written in accordance with NUJ and IPSO standards for fair, accurate, and responsible public-interest reporting. Quotations are drawn from the official transcript and submitted Inquiry documents and are reproduced within the context of fair reporting and public record.

Index

Critical theorists referenced

- David Harvey, The New Imperialism (Oxford University Press, 2003) – “accumulation by dispossession” and the role of the built environment in cycles of creative destruction.

- Brett Christophers, Rentier Capitalism: Who Owns the Economy, and Who Pays for It? (Verso, 2020) – on housing as an asset class and planning as a delivery vehicle for rentier income streams.

- Manuel B. Aalbers, The Financialization of Housing: A Political Economy Approach (Routledge, 2016) – on viability, risk, and investor-led housing provision.

- Doreen Massey, For Space (Sage, 2005) – on space as the product of interrelations and the closing down of alternative futures.

- Loïc Wacquant, “Territorial Stigmatization in the Age of Advanced Marginality” in Thesis Eleven 91(1), 2007 – on how policy and procedure manage and depoliticise urban inequality.

Key inquiry documents and evidence cited

- Aylesham Inquiry Day 4 – Transcript (Southwark, 31 October 2025) – heritage cross-examination of Lewis Eldridge and affordable housing evidence of George Venning.

- Southwark Strategic Housing Market Assessment (SHMA) – Cobweb Consulting, core document 0623, cited in Venning’s evidence on annual housing need (2,932 homes p.a., of which 2,077 affordable).

- Southwark Local Plan (2022) – housing target of 2,355 homes per annum and 35% borough-wide affordable housing benchmark; basis for Venning’s “180% market / 40% affordable” analysis.

- Molior London Residential Development Q3 2025 Report – market data on sales volumes and price per sq ft in schemes of 20+ private units; cited as evidence of a “collapse in demand” for new-build market housing and the cost implications of tall buildings.

- George Venning, Proof of Evidence for Aylesham Community Action (ACA) – analysis of tenure misalignment, the “golden thread” of Southwark’s housing strategy, and the removal of Community Land Trust homes from the Aylesham scheme.

- BPS Chartered Surveyors – Independent Financial Viability Assessment (for LBS) – core document referenced in cross-examination; concludes that the scheme is not financially viable and “cannot support any affordable housing,” making the 12% offer “above the maximum viable.”

- London Plan (2021), Policy H5 (Threshold Approach to Affordable Housing) – framework for “maximum reasonable” affordable housing and viability scrutiny, referenced repeatedly in Harris’s cross-examination.