Liverpool Street Station Redevelopment: A Hearing Designed to Pass, Not to Listen

On 10 February 2026, the City of London Corporation’s Planning Applications Sub-Committee will consider application 25/00494/FULEIA: a phased redevelopment of London Liverpool Street station and surrounding sites, including partial demolition, major alterations to the concourse and structures, and an over-station commercial building reaching 97.67m AOD.

This article sets out first principles of objection: not only what is proposed, but how the City is handling the public hearing—through rules that compress scrutiny into minutes, fragment the civic voice, and treat participation as a procedural event rather than a democratic act.

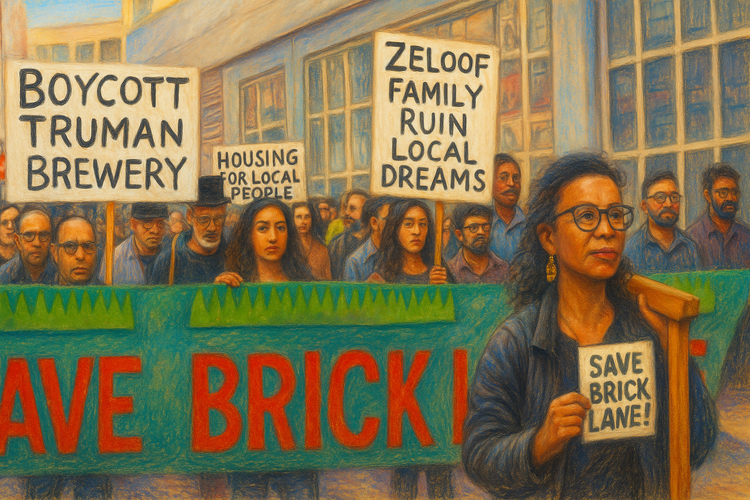

ConserveConnect will publish daily on the Liverpool Street scheme as events unfold. We will track what is said, what is not said, what is treated as “out of scope,” and how planning language—consultation, public benefit, inclusion, “Destination City”—is used to pacify dissent and move a decision to closure. Our reporting will draw explicitly on the critical method developed through our Truman Brewery inquiry coverage and our wider work on London’s redevelopment political economy, including The Billion-Pound Loss: Who Really Profits from London’s Redevelopment Boom?

What follows is the introduction: the frame, the method, and the case against a hearing designed to quickly approve.

Before the hearing: the letter that defines the public’s role

Most members of the public do not encounter planning power in its full institutional form. They meet it in fragments: a consultation website, a glossy rendering, a “have your say” page, a polite email. What makes Liverpool Street unusual is that the City’s own contributor process crystallises the system’s structure in a single document.

On 27 January 2026, the City circulated a contributor letter to people who had already submitted written representations on the Liverpool Street application. It reads like administrative housekeeping: it confirms the committee date, provides instructions, and attaches the public speaking rules. But it also performs something deeper: it defines in advance what the public is allowed to be.

That is why this article begins with the letter. Because the hearing’s limits are not a side detail. They are part of the meaning of the decision.

If planning is meant to mediate conflict in the public interest, then the “public interface” matters. If civic legitimacy matters, then the design of participation matters. If scrutiny matters, then the time granted to scrutiny matters.

And here, the time granted is deliberately small.

I. The sentence that reveals the outcome before the hearing begins

The City’s contributor letter is disarmingly straightforward. It confirms the committee date and states that the Chief Planning Officer will recommend approval. It sets out the speaking rules, the registration deadline, and the boundaries of what the public is permitted to do in the room. (These rules are not accidental; they sit within the City’s published protocols on committee procedure and public speaking.) (democracy.cityoflondon.gov.uk)

That “approval recommended” line is not a technicality. It shapes the psychology of the hearing and the ethics of the process. It tells the public that the administrative trajectory is already set, and that speaking is permitted within a pre-established direction of travel. You can still oppose. You can still put evidence on the record. But you are doing so inside an apparatus whose default setting is “approve,” and whose public interface is rationed to minutes.

This matters because Liverpool Street is not a small scheme. It is a city-scale intervention into a historic interchange and its civic thresholds. It is not simply an architectural proposal; it is a governance moment—one in which a public asset is being reorganised, functionally and symbolically, around a particular model of growth.

If a scheme is consequential, the democratic process should be proportionate. Here, it is the opposite: the greater the scheme, the narrower the public aperture.

II. What is being proposed: remaking the station, then building over it

The application description sets out a phased redevelopment across the station and adjacent sites. In broad terms, it includes partial demolition and extensive alterations to the station, concourse and associated structures; demolition of 50 Liverpool Street; works to Sun Street Passage; remodelling of basements and concourse levels; new circulation elements (lifts, escalators, stairs); reconfigured ticket gates and entrances; new retail and food/drink units; new walkways and public access routes; and major public realm works around Hope Square and Bishopsgate Square. (lamas.org.uk)

Above all of that sits the over-station element: a new building rising to 97.67m AOD, with a commercial programme that includes major office floorspace, terraces, and an auditorium alongside a publicly accessible roof terrace. (lamas.org.uk)

This is where the real politics of the project begins. You can argue endlessly about architectural taste, skyline, or “heritage integration.” But the central fact is more structural: a major public interchange is being remodelled, and above it a substantial commercial development is being installed, with “public access” features folded into an overall destination-and-yield logic.

In modern London, this is a familiar pattern. Public infrastructure is upgraded, “made fit for the future”—and the mechanism used to pay for, justify, or politically stabilise the upgrade is over-site commercial uplift. The station becomes both interchange and platform: a civic threshold and a development base.

The question is not whether stations should ever change. They must. The question is whether change is being steered by public need or by private valuation—and whether the democratic process is strong enough to interrogate that distinction.

III. The hearing rules: a public process compressed into ten minutes

The City’s public-speaking rules are not incidental. They are the constitutional skeleton of this decision.

The City’s published rules governing public speaking at planning meetings set out a tight allocation of time, with objectors and supporters sharing a capped total, and individual speakers constrained to only minutes. (democracy.cityoflondon.gov.uk) In practice, this produces a structure where (a) the public is time-poor by design, (b) the applicant’s case arrives with institutional thickness—reports, presentations, officer framing—and (c) public challenge is compressed into a thin performative strip at the end of a process whose substantive work has already been done elsewhere.

The asymmetry is the point. A system can advertise “public speaking” while ensuring public speech cannot meaningfully alter the decision environment.

Even before we debate the merits, consider what it means to explain—within a few minutes—the implications of:

- demolition and whole-life carbon trade-offs

- station crowding and operational resilience during multi-phase construction

- public realm enclosure and access conditions

- statutory heritage duties and the difference between “retained” and “functionally erased”

- the distribution of value uplift and who benefits

- whether genuine alternatives were properly explored

No serious argument survives in that time unless it is already reduced to slogans.

And once debate is reduced to slogans, it becomes easy to dismiss. “Objectors are emotional.” “Objectors are nostalgic.” “Objectors oppose growth.” “Objectors don’t understand deliverability.” A compressed hearing format helps generate the very caricatures that neutralise opposition.

This is not a neutral procedural choice. It is a method of governance: compress scrutiny until it becomes survivable for the decision.

IV. Consultation, as described by the City: “meaningful engagement” as narrative, not power

The City of London’s planning framework describes engagement as a matter of standards and expectations: how applicants should consult, how communities should be involved, and how consultation should shape proposals. The City’s Developer Engagement Guidance is explicit about the aim: positive and meaningful communication with communities and stakeholders. (City of London) The City’s Statement of Community Involvement similarly sets out how stakeholders will be involved in planning policy and the determination of applications. (City of London)

On paper, this sounds participatory: multi-channel engagement, feedback loops, community involvement, consultation as part of legitimacy.

But the Liverpool Street hearing brings the contradiction into focus:

The more consultation is narrated as essential, the more glaring it becomes when the democratic climax—the committee decision—is structured to make public voice negligible.

This is the core problem with contemporary planning theatre. Consultation is narrated as participatory and inclusive, while decision-making is engineered as narrow and time-starved. The result is a process that can generate a thick archive of engagement while remaining structurally resistant to change.

This contradiction is not unique to Liverpool Street. It is an institutional style: participation as documentation, decision as closure.

Our reporting at Brick Lane named the mechanism clearly: the system allows participation to exist as record while resisting participation as force. In Day Two: The Grammar of Power, we described how procedure and tone can narrow the field of what is speakable until only authorised language remains. (ConserveConnect) Liverpool Street repeats the narrowing—less through courtroom cross-examination, more through time rationing and procedural gating.

V. The hearing as a machine for fragmenting opposition

The ten-minute rule (or any equivalently compressed allocation) does more than shorten speeches. It forces objectors into internal negotiation.

If multiple constituencies oppose the scheme—heritage campaigners, commuters, disability advocates, local workers, nearby residents, conservation bodies, station users, climate groups—then a narrow total allocation means these constituencies must choose which harms are allowed to exist publicly.

That is not coordination; it is triage.

The public’s main resource—time—is rationed; institutional time is not. The applicant’s narrative arrives through volume: documents, diagrams, officer summaries, policy framing, professional witnesses, and the calm authority of a pre-structured report. The public arrives with urgency and a stopwatch.

This is why the format matters. It produces a public record of objection that is necessarily incomplete. And incompleteness is then used to argue that the objection is weak.

At Brick Lane, we described the “grammar of power” as the way authority narrows a conversation to what is procedurally admissible, then treats what remains as the whole truth. (ConserveConnect) At Liverpool Street, the door is closed not by legal counsel, but by the agenda clock.

VI. Planning is not a closed algorithm—and yet the public is treated as if it is

One of the most useful lines from our Brick Lane reporting is also one of the simplest:

Policy provides guidance, not automation.

Modern planning institutions increasingly behave as if planning were an algorithm: input documents, consult stakeholders, tick compliance boxes, balance harms and benefits, output approval with conditions. The process becomes procedural rather than deliberative. It becomes a system that can be “streamlined.”

But planning is not a closed system. It is not meant to deliver certainty to capital; it is meant to mediate conflict in the public interest, with transparency, and with civic legitimacy.

When the public is offered only minutes to oppose a scheme of this magnitude, what is being asserted—implicitly—is that planning is already decided by experts and documents, and that public speech is an accessory. Participation becomes a symbolic gesture: a way to complete the democratic image.

Yet the City’s own engagement rhetoric says the opposite: that engagement improves outcomes and balances needs. (City of London)

So we must ask: which is true in practice? If consultation is essential, why is objection time rationed? If collaboration is real, why does the public not have any reciprocal capacity to interrogate officer framing in real time?

You cannot claim consultation as a virtue while designing decision-making as a narrow funnel. That is not engagement. It is optics.

VII. “Destination City”: the conversion of civic space into yield

Liverpool Street sits within a jurisdiction whose planning philosophy is explicitly tied to maintaining the Square Mile’s position as a global financial centre and expanding its attractiveness as a leisure and cultural destination. The City’s Destination City agenda is framed as a growth strategy—making the City a “magnetic destination” where people choose to live, work, learn, and explore. (City of London)

This matters because it prevents Liverpool Street from being misread as merely a station upgrade. It is a growth project: a reprogramming of public infrastructure and public realm in the service of a particular model of economic identity.

This is where our “Billion-Pound Loss” framework becomes operational. The question is not only whether a scheme is technically plausible or architecturally acceptable. The question is who captures the uplift created by redevelopment; who bears the costs; who loses access, permeability, and human-scale civic space; and how “public benefit” is packaged to stabilise the legitimacy of a fundamentally commercial logic.

At Brick Lane, we described planning consent as a conversion interface: a moment where political consent becomes financial security. In Planning as Alibi, Capital as Client, we wrote about consent as the hinge between urban place and asset value. (ConserveConnect)

Liverpool Street operates differently—transport infrastructure rather than “digital need”—but the grammar is adjacent. Public function becomes the legitimating wrapper for private uplift. Public realm improvements become the narrative of benefit. “Publicly accessible” terraces become symbolic gifts embedded in an overall commercial scheme.

The key question is not whether the scheme includes public benefits. Most large London schemes do. The question is whether those benefits are proportionate, unconditional, and genuinely public—or whether they are fragments offered as civic compensation for an extraction model embedded above.

When “public benefit” is presented in an approval cycle designed to minimise public speech, it stops being benefit and becomes alibi: a rhetorical device used to justify scale and secure consent.

VIII. Procedural barriers are political barriers

Even if the hearing is “open,” the real question is: open to whom?

Procedural gating—deadlines, eligibility rules, registration requirements—selects for those with time, confidence, literacy in planning bureaucracy, and the ability to monitor committee calendars. It filters out many of the very users most impacted: shift workers, disabled travellers, time-poor commuters, non-native English speakers, those unfamiliar with planning procedure, those without the resources to track the process.

In other words: a right can exist on paper, while becoming unusable in life.

Our Brick Lane reporting gave language to this: participation without comprehension is participation denied. (Not because the public is incapable, but because the system is designed around professional fluency and institutional time.) Liverpool Street risks producing the same denial—through timetable and formality rather than courtroom atmosphere.

This is why the “how” of the hearing is not a side story. It is part of the harm.

IX. A hearing that treats the public as noise cannot claim democratic legitimacy

Planning decisions create long-lived outcomes. They shape streets for decades. They affect environmental performance, movement patterns, access, identity, and the distribution of value. In a plan-led system, they also test whether policy is meaningful or merely rhetorical.

When such a decision is structured so that public speech is effectively symbolic, the legitimacy of the decision becomes thin. The hearing becomes a rite, not a forum.

A hearing designed to listen would do at least three things differently:

- Scale speaking time to scheme complexity, rather than forcing opposition into internal triage.

- Allow reciprocal interrogation of key framings—at minimum through structured mechanisms that enable public challenge to officer assumptions, not only officer challenge to public claims.

- Create deliberative time—time for Members to weigh alternatives and trade-offs, not merely to process an agenda.

Instead, current practice tends toward rationing, gating, and asymmetry: the public can be “heard,” but the system cannot be meaningfully tested by the public in the room.

That is why “A Hearing Designed to Pass, Not to Listen” is not rhetoric. It is structural description.

X. The substantive case against the scheme: why Liverpool Street cannot be reduced

This article focuses on process because process is where power hides. But the breadth of substantive objection is precisely why compression is indefensible. Liverpool Street touches multiple domains of public interest that cannot be responsibly reduced to a few minutes.

1) Heritage and continuity: “retained” versus “functionally erased”

Liverpool Street is not a neutral site. It carries built memory, civic identity, and the public meaning of London as a city of layered infrastructure. Heritage harm is rarely only about what is demolished. It is also about the reprogramming of place: whether what remains functions as heritage, or becomes heritage-image—texture retained while the civic logic is rewritten.

National policy is clear that heritage significance, setting, and the public value of the historic environment are material planning considerations, not optional flavour. (GOV.UK) The question is not whether heritage is mentioned in a Design and Access narrative. The question is whether the scheme sustains significance—or turns heritage into commodity.

Our Brick Lane piece Heritage as Commodity warned against “heritage-led” language becoming a pricing mechanism: heritage packaged as lifestyle texture within a premium offer. (ConserveConnect) Liverpool Street must be tested against the same risk: heritage presented as ingredient in a “Destination City” offer, not as a duty.

2) Public realm, access, and enclosure: what does “public” mean in managed space?

“Public realm works” and “publicly accessible” terraces can be genuine civic contributions—or conditional spaces: managed, surveilled, subtly exclusionary. The difference is operational: hours, rules, security practices, behaviours permitted, protest and gathering tolerated, the “feel” of who belongs.

A station is one of the last truly mixed public interiors in London. When you intensify commercial programming and build over it, you risk converting movement into consumption and public life into footfall. Civic permeability becomes tenancy logic.

This is not a moral accusation; it is a pattern. Contemporary development frequently supplies “public access” while changing the meaning of public space—through management regimes that are rarely visible at the approval stage, but decisive in lived reality.

3) Transport function versus commercial uplift: does the station serve movement or monetisation?

Liverpool Street’s core purpose is movement and access. Any scheme must be judged on operational resilience: crowding, circulation, safety, legibility, step-free access, and the lived experience during construction phases.

But the proposal includes major remodelling of entrances, concourses, and circulation elements. (lamas.org.uk) The hard question is whether station function is genuinely improved—or reordered around commercial frontage and development servicing. A few minutes of public speech cannot responsibly test that trade.

4) Climate realism and demolition-led redevelopment: embodied carbon is not a footnote

Demolition is not neutral. It destroys embodied carbon and commits the city to a high-carbon rebuild unless reuse is genuinely prioritised. In London planning, “green” claims too often arrive after demolition is already embedded—performance narratives layered onto a fundamentally extractive material act.

You cannot claim climate seriousness while treating demolition as merely “enabling.” That is not sustainability; it is sequencing rhetoric.

5) The distributional question: who benefits, who pays?

This is the question planning culture often tries to exile because it is political rather than technical. But it is central in a financialised city.

Who captures uplift created by over-station commercial development? Who bears the costs of disruption during construction? Who inherits long-term operational effects? Who gains the “Destination City” benefits—and who is priced out of the city as intensification continues?

Our Brick Lane reporting framed this structurally: public risk underwrites private return, and infrastructure becomes an investable platform. (ConserveConnect) Liverpool Street may be the next test of whether the City can speak honestly about that trade.

XI. Why ConserveConnect is publishing daily

Because the hearing format is narrow, the public record must be widened elsewhere.

If the committee can offer only minutes for all objectors, then the responsibility of public journalism is to create a parallel space where complexity is allowed to exist—where arguments can be made at full scale, where evidence can be read slowly, and where “public benefit” can be tested against distribution and governance rather than asserted as a slogan.

This is what our Brick Lane reporting did: it treated procedure as evidence, and it treated the hearing room as a civic mirror. It did not only report what was said; it reported what the structure of the process allowed to be said.

Liverpool Street demands the same method—perhaps more urgently, because the committee format is faster and less porous than an inquiry.

We will publish daily on:

- the hearing rules and what they do to democratic voice

- the language of “Destination City” and the political economy it encodes (City of London)

- the scheme’s impacts on heritage continuity and civic identity (GOV.UK)

- public realm and access—what “public” means in managed space

- station function and operational consequences during construction

- climate and demolition: embodied carbon and alternatives

- value capture: the distribution of uplift and the pattern of London’s redevelopment boom

This first article is the introduction: the claim that the democratic deficit is not a side story but part of the scheme’s meaning.

XII. The ten-minute city: what the rules reveal about how London is governed

Liverpool Street is a station, yes. But it is also a symbol: of London’s openness, its movement, its public interior. When the decision about its remaking is mediated through minutes of objection, the City reveals something about its governance priorities.

It reveals a preference for efficiency over deliberation, for procedural completion over democratic time. It reveals a belief that the public’s role is to be “consulted” and then processed—heard, but not listened to; documented, but not empowered.

At Brick Lane, our reporting warned that democracy is itself a commons—sustained through participation and eroded when enclosed by private power. Liverpool Street presents the same warning in committee form:

When democratic time is rationed, the city is not merely rebuilt; it is re-owned—socially, politically, and morally.

The hearing will go ahead. The rules are set. The Chief Planning Officer recommends approval. (democracy.cityoflondon.gov.uk)

The task now is to refuse the compression. To keep the argument at full scale. To insist that planning is a civic act, not a clearance mechanism; and that participation is not a ceremonial gesture but the condition of legitimate change.

ConserveConnect will publish daily until this decision, and the system behind it, is fully visible.

Practical links for readers who want to act now

- The City of London’s meeting page for the Planning Applications Sub-Committee (10 February 2026) is here. (democracy.cityoflondon.gov.uk)

- The City’s published rules governing public speaking (Appendix B) can be read here. (democracy.cityoflondon.gov.uk)

- The Victorian Society’s guide—“How to object to the harmful plans…”—sets out a clear, accessible route for submitting objections. (The Victorian Society)

- The City of London planning portal’s documents tab for the scheme can be accessed here. (lamas.org.uk)