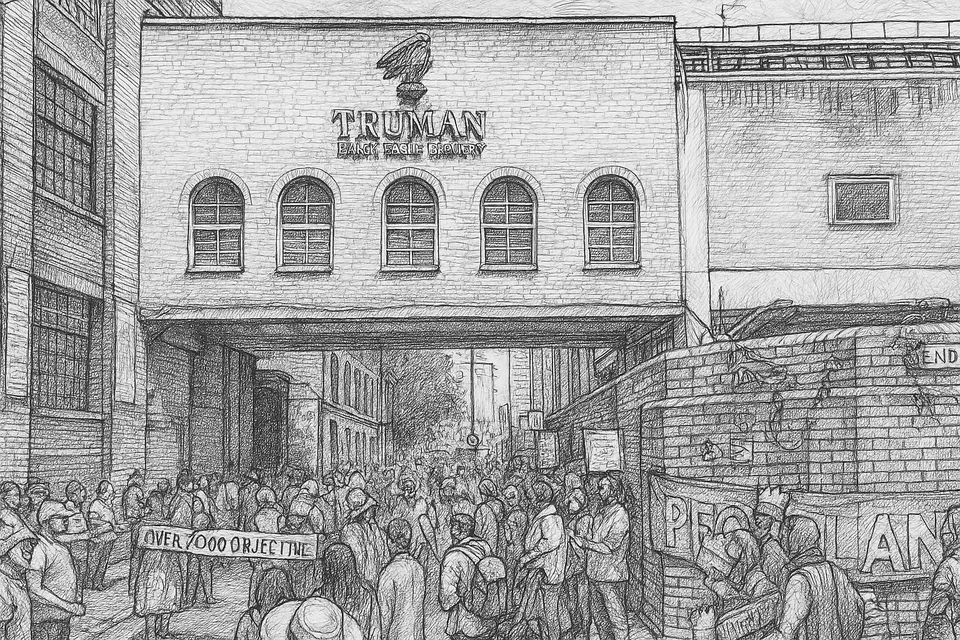

From Heritage to Humanity - Day 6 at the Truman Brewery Inquiry

The sixth day of the Truman Brewery Public Inquiry opened with the conclusion of Michael Dunn’s re-examination and closed with the questioning of Simon Henley, architect of the scheme’s most contested building. Together, their evidence traced the hand-over from policy to plan — from heritage in principle to heritage in form. Counsel for the appellants, Russell Harris KC, sought to prove that the project had been “heritage-led” from its inception. By 1 : 45 p.m., as the microphones clicked off, the phrase had been spoken, tested, and worn thin. What remained was the question that will shadow the Inquiry to its end: what does “heritage-led” really mean, and who gets to define it?

Inside the Room

By ten o’clock the air was thick with paper. Laptops hummed, highlighters uncapped. Behind the pink-topped tables the public benches half-filled with teachers, traders, students, campaigners — the same faces who had followed every day of the hearing. The inquiry’s rhythm was by now familiar: precision first, persuasion later.

No visual presentations were used. All questioning proceeded by reference to printed or digital documents, which participants located individually as each citation was made.

Re-establishing the Timeline

Harris began with the accusation that heritage advice came late. Dunn leaned toward the microphone and disagreed. He confirmed that Kevin Murphy Heritage (KMH) had already been engaged with planning officers well before his own appointment in 2024. Harris explained that documents showed KM Heritage attending early meetings, appearing on agendas, and contributing to view-assessment work with officers Gareth Gwynn and Ewan McGillick.

He then walked the room through the paperwork:

– the Initial Heritage Commentary (June 2023);

– a Pre-Application Presentation (May 2023) listing KM Heritage among the design team.

Heritage, he said, was “embedded from the start.” Dunn agreed.

Reading the Documents

The Initial Heritage Commentary was read aloud from the bundle:

“The aesthetic quality of the area around the site is, however, mixed. The underlying historic grain and the surviving historic buildings … coexist with significant amounts of later development of indifferent or poor quality.”

Asked whether this was judgment or description, Dunn replied: “That is judgment and analysis — well, analysis and judgment, all three really.” The exchange followed Harris’s reading of paragraph 36 verbatim from the report. Harris continued through the document; each phrase was treated as evidence of evaluation rather than mere record. Engagement equalled respect; respect equalled conservation. The reasoning closed neatly back on itself.

The “Founding Principles”

When the May 2023 pre-application document (ID 16) was discussed, its language was disarmingly simple. Four short statements set out what the team called their “founding principles” — a heritage shorthand for reassurance:

- Celebrate surviving brewery fabric.

- Respect the site’s industrial scale.

- Frame public views of the chimney.

- Re-create yards and passages following the historic plan.*

Harris read each principle aloud from the document, pausing after each and asking whether it was “a heritage matter.” “That’s a heritage matter,” Dunn replied. “It is, yes.” Four principles, four confirmations — enough to construct a lineage of care.

Yet the principles themselves were aspirations, not tests. They offered no metrics, no hierarchy of significance. Their power lay in repetition. Spoken aloud, they became the record of intent; written down, they became its proof. Heritage, repeated and acknowledged, became self-validating.

Guidance as Evidence

From the principles, Harris moved to policy. He introduced Historic England’s Good Practice Advice Note 3 (GPA 3) — the national manual for assessing “the setting of heritage assets.” Its five verbs — identify, assess, evaluate, minimise, decide — are recited so often in inquiries that they have become a litany of professional faith.

Dunn delivered them from memory, without hesitation: “Identify, assess, evaluate, minimise, decide.” The Inspector nodded; the shorthand entered the transcript.

Nothing new was added — no site-specific evaluation, no visual evidence — yet the citation itself carried authority. It implied compliance with an invisible procedure.

Harris also referred to the green-boxed section (page 7) of GPA 3 concerning “designed or associative views,” prompting Dunn to explain that none of the identified views of the Truman chimney were of that kind. In the theatre of planning, process often suffices as performance. Here it was the act of recitation — not the outcome — that proved adherence. Guidance, once invoked, did not merely inform the evidence; it became the evidence.

Block J and the Question of Scale

Next came Block J — the building that has haunted the inquiry since the first day’s diagrams. Early drawings showed an eight-storey block rising above the chimney’s shoulder. The March 2024 Quality Review Panel (QRP 2) urged moderation, and the height was reduced to seven storeys by that meeting.

Harris treated the revision as proof of responsiveness. Was this reduction the product of heritage advice? Dunn agreed, adding that the final design aligned with Historic England, the Greater London Authority, and the emerging Local Plan. Agreement was presented as validation — consensus as correctness.

To the untrained ear it sounded like evidence of balance; to those in the gallery it sounded like the flattening of difference. The numbers — eight, then seven — replaced discussion of proportion, shadow, or skyline. “Responsive adjustment” became the phrase of the hour: technical, uncontroversial, and final. The design, once contested, was now archived as reasonable.

The Brewery and Its Afterlife

Harris closed with context. “For decades and centuries it was a brewery,” Dunn said. “That stopped … and there will be new uses and new activities happening on this site.” Continuity was redefined as succession — heritage as the smooth replacement of one economy by another. The Inspector asked whether new uses might erode character. Dunn replied that “change and continuity are both part of heritage.” The phrase settled like a verdict.

At 10 : 55 the Inspector thanked Mr Dunn and confirmed that his evidence was complete. Folders closed, screens refreshed. Moments later Simon Henley, director of Henley Halebrown and author of the scheme’s architectural design, took the witness chair. Where Dunn had spoken the language of policy, Henley spoke the language of construction — proportions, light, and material. The morning shifted from the rhetoric of heritage to the practice of building.

The Architect’s Turn: Simon Henley

Simon Henley’s task was to defend the architecture itself — the proportions, materials, and intent of the scheme now defined by Block J. Where Dunn had spoken the language of policy, Henley would speak the language of practice.

Hugh Flanagan, for Tower Hamlets Council, began quietly. Had any written heritage advice guided the design of Block J before Dunn’s arrival in February 2024? Henley paused. “We don’t provide any expert heritage documentation, no.” Pressed again, he admitted: “That is seemingly correct.” Flanagan clarified that no written expert heritage advice had informed the initial eight-storey design produced in July 2023. The point was simple: the building that now defines the application was drawn before any formal heritage witness entered the process. Flanagan let the silence make the argument.

Height and Context

Flanagan referred to design documents, reading the measurements aloud: surrounding heights between ten and sixteen metres; Block J — twenty-five and a half metres to parapet, twenty-seven to top of plant.

“You’ve called this a nuanced response,” he said. “It is not nuanced to exceed every neighbouring roofline, is it?”

Henley answered carefully: “It’s not purely a question of height. It’s what is seen, how it is experienced from the ground. It’s a judgment — heritage, daylight, sunlight, amenity, quality of homes. All of those together.” Flanagan replied evenly: “Understood. Those are my questions.” The exchange left the contrast intact: numbers versus perception, regulation versus intuition.

From Form to People

When Flanagan concluded his cross-examination, the Inspector invited questions from the other parties. Flora Curtis, counsel for the Rule 6 Party Save Brick Lane, rose to begin. Her tone was measured but unflinching, and her focus diverged sharply from the technical exchange that had just ended. Where the Council’s advocate had tested height, scale, and skyline, Curtis turned to the human dimensions of design — accessibility, equity, and everyday use. Her questions would shift the morning’s lens from architecture as object to architecture as environment.

Inclusive Design and Public Consultation

Flora Curtis, counsel for the Rule 6 Party Save Brick Lane, shifted the morning to a different register — away from heritage and toward people. She opened the bundle at London Plan Policy D5, reading from its requirement on inclusive design.

“Design and Access Statements must include an inclusive-design statement,” she said. “I don’t see one in yours.” Henley looked down. “I think you’re right.”

Curtis then directed him to the Equality Impact Assessment (July 2024).

“This is retrospective,” she said. “An assessment of results, not process.”

“There is no evidence that inclusive design or impacts on persons with protected characteristics were embedded at the earliest stage.” Henley replied: “I think you’re telling me that.”

Turning to the Design and Access Statement, she noted that while it listed consultation events, none recorded any public feedback.

“There’s no evidence here of what residents or community groups said,” she observed. Henley agreed: “That is obviously the case from what I can see.”

Finally, Curtis asked about car-parking and affordable housing. Those fundamentals, Henley said, were “beyond my instruction.”

Her exchange exposed a gap that had run beneath the morning’s technical debate — a design process framed around form and compliance, but silent on inclusion, access, and equity.

Summing Up the Morning

The morning exposed the quiet hand-off between expertise and authorship. Mr Dunn confirmed that heritage advice existed in outline before design began; Mr Henley confirmed that no written guidance shaped his early drawings. Heritage had been present in conversation but absent in command.

What followed was a design carried forward by inherited assumptions — height, car-free status, limited affordable housing — constraints presented as givens rather than as choices. Responsibility dispersed across consultants until no single hand could be said to lead.

Procedure as Proof

Where Dunn recited the language of policy, Henley narrated the logic of process. Each spoke fluently in the dialect of compliance. Every citation of a plan, a review panel, a policy clause acted as its own evidence. The question “What is heritage?” was displaced by “Was heritage consulted?” The appearance of consultation replaced the substance of influence. In this culture of procedure, method became both cause and consequence — a system that proves itself by repetition.

The Missing Dimensions

Flora Curtis’s questioning revealed the unspoken absences: inclusion, access, equity. London Plan Policy D5 requires designers to address the experience of London’s diverse population, yet the scheme had no inclusive-design statement. Its equality assessment arrived after the design was fixed.

The Design and Access Statement listed consultation events but none involving the public. Within a process that celebrates engagement, those most affected were never recorded as participants. The drawing began where dialogue ended.

Heritage as Alibi

By early afternoon, “heritage-led” had hardened into a procedural defence. Dunn supplied the authority of heritage; Henley supplied the authority of architecture. Together they formed a single rationale: the scheme was responsive.

But responsiveness, as the day revealed, can mean reaction without responsibility — a posture rather than a principle. At 1 : 45 p.m. the microphones clicked off; at 2 : 30 p.m., the Inquiry would hear from the appellant’s witness on the Data Centre. The morning closed not with resolution but with substitution: heritage invoked to explain process, and process standing in for judgment.

Editorial Note

This report is a fair and accurate account of open proceedings at the Truman Brewery Public Inquiry (Day 6, Morning Session) and is protected by qualified privilege under Schedule 1 of the Defamation Act 1996. Commentary reflects the author’s analysis in line with NUJ and IPSO standards.