Final Day — Brick Lane on the Scales: Class, Capital and the Financialised City

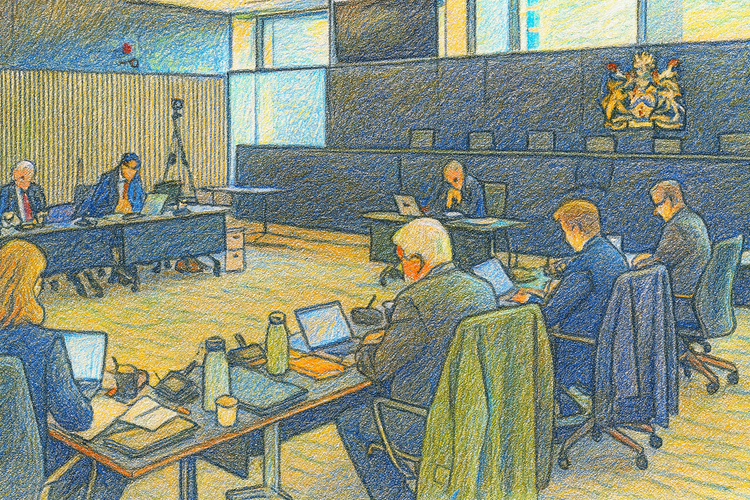

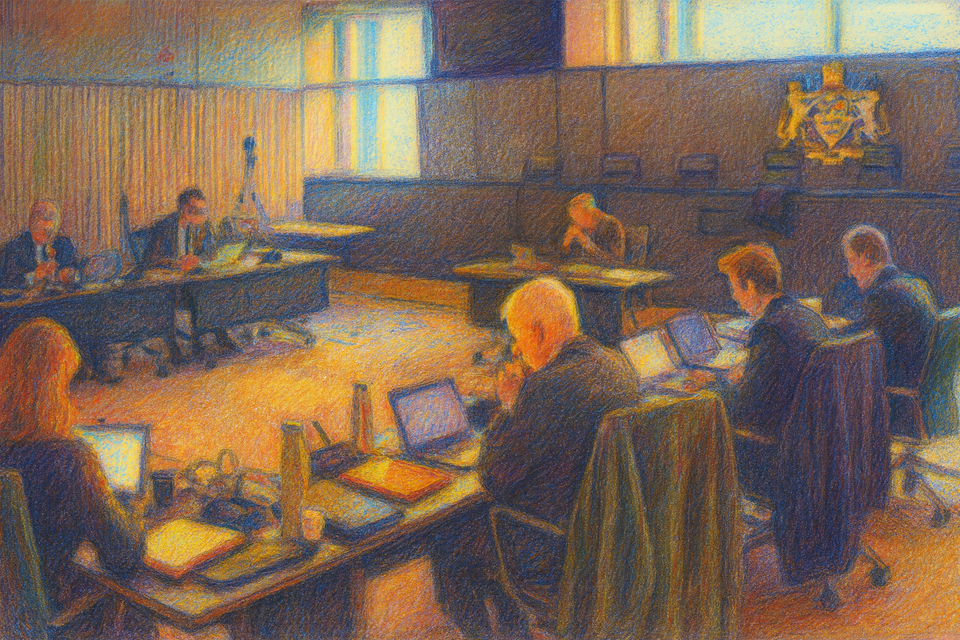

31 October 2025, Tower Hamlets Town Hall. On the last afternoon of the Truman Brewery Inquiry, the microphones were the same, the bundles the same, the cast of characters mostly unchanged. What shifted was the frame. The closing submissions no longer pretended this was only a dispute about façades and floor-to-ceiling heights. In a quiet way, each advocate was forced to say whose side the planning system is on.

Prologue — The Room and the Line of Sight

The new Town Hall chamber in Whitechapel looks like a cross between a courtroom and a trading floor. Long black tables arc in a shallow horseshoe. Laptops glow. Water bottles stand in a neat line next to piles of marked-up proofs. At the far end, beneath the borough crest fixed high on a dark wall, the Inspector sits at a raised desk, looking down the central aisle towards the parties.

On one side, the Truman team: King’s Counsel, juniors, planning consultants, the data-centre specialist. On the other, counsel for Tower Hamlets, flanked by officers whose budgets are being hollowed out while their casework grows. Further along, the Rule 6 table for Save Brick Lane. Behind them, a patchwork public gallery: residents, campaigners, council staff, a few curious observers; some seats empty, some taken, never quite packed and never quite bare. Beyond the chamber, a webcast watched from kitchens and back offices along Brick Lane itself.

The sociologist Loïc Wacquant describes rooms like this as “class theatres”: spaces where the relationships between owners, officials and residents are staged and then translated into law. The choreography in Whitechapel fits the description. On one axis sit those who own ten acres of inner-London soil and want to reprogramme it for offices and servers. On another sit those who live and work in the shadow of that soil and are asking not to be squeezed out. In the middle sits a representative of the state, asked to decide which of these interests constitutes “need”.

I. The Appellant’s Story: Growth Without Biography

For the appellants, Brick Lane is first and foremost an asset. Their closing submissions begin with an ode to the Truman Brewery as a “unique and remarkable place,” lovingly curated over three decades into a creative quarter, and move quickly to the language of optimisation. The London Plan’s designation of the City Fringe as a growth area becomes a mandate to “build on the Estate’s strengths.” The national planning framework’s call to make “effective use of land” becomes a licence to thicken offices and stack a data centre where family flats might otherwise go.

In this story, new SME-orientated offices are not one possible future among others but the natural destiny of the site. The borough’s own Employment Land Review, which records no general shortage of office floorspace and only equivocal evidence for extra SME demand, is acknowledged and then reframed as proof that Truman forms a special micro-market that cannot be served elsewhere. The fact that thousands of residents in the same borough cannot find a habitable room, let alone a studio with polished concrete floors, enters only as background.

The data centre on Grey Eagle Street is treated in the same way. We are told there is an “urgent national need” for new capacity and that this small, 3MW facility is “possibly the best remaining site in the capital” to serve the City’s financial cluster. Recent government decisions on much larger data-centre schemes, where far more capacity was given only “significant” weight, are set to one side. Here, the benefit must be treated as “very substantial.”

The economic geographer Brett Christophers uses the term rentier capitalism for an economy organised around people and institutions who make their money by owning assets and charging others to use them. Land, office blocks, roads, energy networks, data centres: these become engines for rent. Planning and regulation are reshaped to protect their income streams. Looked at through that lens, the Truman data centre ceases to be a neutral piece of infrastructure. It becomes a small power station for future rents, backed by the full authority of the state if permission is granted.

Housing appears as a supporting actor. The forty-four flats in Block J, a mere six of them at social rent, are presented as a meaningful contribution to the housing crisis, but only so long as they do not “dim the bright light” of Truman East’s commercial role. What C. Wright Mills once called the “biography” of the borough’s overcrowded households – their overcrowded rooms, their waiting-list years, their rent hikes – is mentioned, but the real drama unfolds elsewhere, at the level of “structural trends”: the long swing of policy towards offices, servers and curated leisure as the proper uses of central land.

It is a tidy story. It has almost no people in it.

II. The Council’s Story: Plan-Led, and Tugged Between Classes

Tower Hamlets’ closing brings people back in, if somewhat cautiously. Richard Wald KC begins with heritage and townscape. The entire appeal site lies within the Brick Lane and Fournier Street Conservation Area, “one of the most important historic areas in London.” The proposed massing at Truman East, the re-framing of Allen Gardens, and the data centre’s blank facades on Grey Eagle Street together amount, the Council says, to harm of real weight. The statutory duties under sections 66 and 72 of the 1990 Act, which require “special regard” to preservation, are presented as a hard edge that economic aspirations must not cross.

From there he turns to housing. Tower Hamlets has some of the worst overcrowding in England. It carries waiting lists long enough to be measured in decades, not years. Against that reality, to bring forward only forty-four dwellings on a ten-acre site – with acknowledged daylight problems in the social units – is not a marginal disappointment but a structural failure. The development plan expects brownfield land like Truman to shoulder a serious share of that burden. The appellants propose instead to freeze most of it into a commercial campus.

In the work of housing scholar Manuel Aalbers, cities like London have become storage devices for global wealth. Homes and neighbourhoods are turned into financial products; land is priced less by the needs of local residents than by the returns demanded by investors. Local planning policy is one of the few tools left that can push back. In that context, Wald’s submissions can be read as an attempt to wield the same instrument in the opposite direction. The London Plan and Tower Hamlets Local Plan, read as a whole, still contain a faintly social-democratic DNA: language about meeting housing needs, sharing growth, respecting heritage as something more than a brand. The Council’s case is that, on any honest reading, these appeals cut across that DNA, and no amount of invocation of “growth” or “national infrastructure” justifies the breach.

The limits of that attempt are never far away. The borough knows what happens when local preferences collide with central government priorities and the long game of market actors. Perhaps that is why Wald does something unusual for a closing in a planning inquiry. He records the depth of public opposition as a fact in its own right, noting that this has been a “remarkable inquiry” in terms of the number and intensity of objections, and that support for the scheme has come from a relatively narrow set of existing estate tenants, already positioned to benefit from the proposed changes.

Mills argued that the task of social analysis is to “grasp history and biography and the relations between the two.” The Council’s closing is an attempt—within the polite limits of advocacy—to do exactly that: to connect the overcrowding of Banglatown families, the erosion of small traders, and the historic significance of Brick Lane to the way this particular piece of land is being inscribed in national policy.

III. Save Brick Lane’s Story: Biography Refuses to Leave

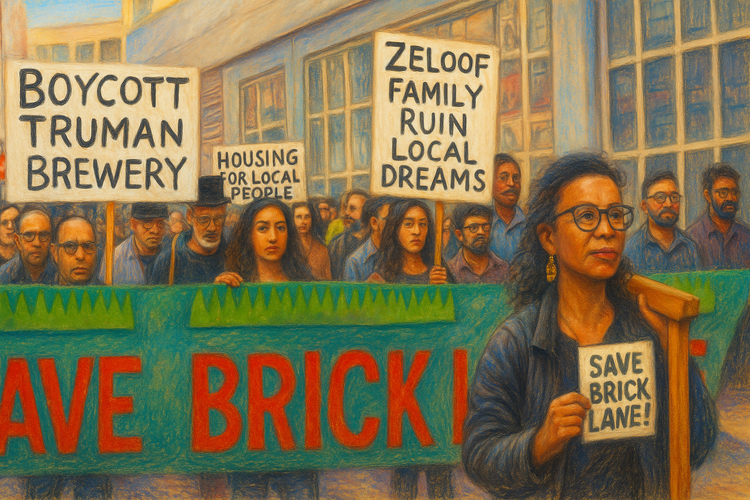

Save Brick Lane’s closing goes further, tying biography and structure directly together. Flora Curtis begins not with paragraph numbers but with the people who filled the public sessions: Bengali families in overcrowded flats, traders with insecure leases, residents who described Brick Lane as “blood and breath,” “the heart of our community,” “the first Banglatown in the West.”

She reminds the Inquiry that Bangladeshi households in Tower Hamlets have far lower average wealth and higher poverty rates than their white British counterparts; that they are more likely to live in overcrowded conditions, more exposed to sudden rent increases or eviction; and that they live disproportionately in the streets that will be most affected if the Truman appeals are allowed. In other words, they stand to lose the most and gain the least from what is proposed.

Wacquant uses the term “relegated spaces” for districts like this: areas where poverty, racialisation and state power are layered together, and where policy often oscillates between neglect and restructuring. In the long history of the East End, Brick Lane has been such a space many times over: for Huguenot weavers, Jewish garment workers, Bengali migrants and, more recently, artists and low-paid service workers. The Truman Brewery scheme, SBL argue, is simply the latest phase: not an intervention for those who live there, but an intervention on the space they occupy.

Curtis then dissects the scheme’s claimed “public benefits.” The jobs, she notes, are overwhelmingly in sectors that already recruit through networks and qualifications that working-class and migrant residents struggle to access. The affordable workspace is designed as office-type space, poorly matched to a local economy of sari shops, grocers and restaurants. The two “community centres” are rooms within a largely privatised estate, offered for thirty hours a week of bookable use rather than as spaces secured permanently for the neighbourhood.

In the language of the American sociologist C. Wright Mills, the distinction between “personal troubles” and “public issues” falls away. Overcrowded flats, shuttered shopfronts and the creeping sense of being unwelcome on your own street are not private misfortunes; they are the everyday face of decisions taken in rooms like the Town Hall chamber, under coats of arms, in the name of “good growth.”

Above all, SBL put a name to what the appeals would do to the land itself. If granted, they would effectively lock the Truman estate out of serious housing use for the lifetime of the new buildings. Ten acres at the heart of the borough would be converted into a permanent commercial and data campus at the moment when the borough most needs sites for social homes.

Aalbers calls this “the financialisation of housing”: the process by which land and buildings are transformed into financial assets, governed by the logic of return rather than shelter. In Brick Lane, that logic does not necessarily produce towers of luxury flats. It can also produce something more perverse: the refusal to build homes on prime land at all, keeping it clear for more profitable offices and server halls.

IV. Financialisation in One Street

Across twelve days of hearing and twenty articles in this series, the same sequence has repeated. First, a historic working-class, migrant district is rebranded as a “creative quarter” or “opportunity area.” Second, its existing fabric is re-described as “underused” or “fractured,” its value measured not in the lives it holds but in the yields it fails to deliver. Third, a technical language of optimisation, viability and infrastructure is deployed to justify a shift from low-rent, socially dense uses to higher-rent, lower-density ones. Finally, the people displaced or priced out by that shift are informed that the process was lawful, their representations were “taken into account,” and that they have been heard even as the decision goes the other way.

The theorists are useful here because they give names to what the Inquiry has made visible.

Christophers’ “rentier capitalism” describes an economy in which the central struggle is over control of assets and the income they generate. Aalbers’ “financialisation of housing” describes how homes and neighbourhoods have been turned into investment vehicles. Wacquant’s work on relegated spaces explains why districts like Brick Lane are often chosen as the stage on which these processes play out: they are close enough to central land values to be worth reworking, and politically marginal enough that their protests can be contained.

C. Wright Mills, writing long before any of them, warned that if we cannot connect what happens in “the very shaping of a man’s life” to what happens “in the larger structure of society,” we are left with either private despair or abstract fatalism. Brick Lane has offered, over these weeks, an object lesson in how to make that connection. The tenants who described mould and overcrowding, the traders who spoke about rising rents and changing clientele, the residents who traced the history of racist attacks and community defence along the street: together they have provided the biographies. The closing submissions have exposed the structure.

Once that connection is made, it becomes harder to treat the Truman appeals as a neutral “national decision” about digital infrastructure. It is, in plain terms, a choice about whether a working-class, largely Bengali district is to be used as a platform for new rent streams, or whether the planning system is willing, for once, to privilege its residents’ right to remain.

V. The Decision Behind the Decision

Formally, the Secretary of State will have to decide:

- whether the appeals accord with the development plan read as a whole;

- whether any heritage harm is outweighed by public benefits;

- whether other material considerations justify departing from local policy.

But beneath those questions lies a more basic choice.

Either the state confirms Brick Lane as another node in the financialised, rentier city – a place where land is programmed to host assets first and communities second – or it interrupts that logic, however modestly, by upholding a refusal that puts housing, heritage and local equality first.

If the appeals are allowed, the message will be clear:

- a scheme that drastically under-delivers housing on a prime site, causes accepted heritage harm and embeds a new infrastructure rent can nonetheless be rebadged as “good growth”;

- local attempts to plan for residential-led, community-oriented development can be overridden when they conflict with owners’ asset strategies;

- consultation and equality analysis that large sections of the community could not meaningfully access is sufficient to legitimate a generational shift in land use.

If the appeals are dismissed, it will not dismantle rentier capitalism in London. But it will mark a rare moment when, in Wacquant’s terms, the state refuses to treat a relegated territory as raw material for another round of restructuring, and instead recognises the claims of those who have held the street through neglect, racism and earlier waves of speculation.

Coda — Names for What Happened Here

It might seem, at first glance, that the books and theories have very little to do with a narrow room in Whitechapel and a set of plans for a brewery site. But they help explain why the case feels so familiar to people who have never heard of them.

When the economic geographer Brett Christophers writes about rentier capitalism, he is describing an economy that many households on Brick Lane already recognise: one in which they pay, month after month, for access to things someone else owns – homes, energy, transport, now data infrastructure – while their own incomes stand still.

When Manuel Aalbers writes about the financialisation of housing, he is describing a city that many tenants already see around them: streets where property is bought and sold like a bank product, where the question is not “who needs this home?” but “what yield can this unit produce?”

When Loïc Wacquant writes about “relegated spaces,” he is describing the feel of places that are always first in line for cuts and last in line for investment, except when their land is suddenly wanted for something else.

And when C. Wright Mills calls for a “sociological imagination,” he is inviting us to do exactly what this Inquiry has forced into the open: to connect the damp flat and the shuttered café to the policy document, the ministerial letter and the developer’s business plan.

You do not have to read any of them to understand the stakes. If you are waiting years for a secure tenancy, if your shop rent goes up while the new places around you cater to people on very different incomes, if you notice that every consultation seems to arrive only after the real decisions have been made, you already know the shape of the argument. The only real question is whether the system that calls itself “plan-led” is willing to know it too.

When the Inspector closed the Inquiry, the gallery emptied in twos and threes. Outside, Brick Lane was still there: fryers hissing, shutters rattling, children weaving between tourists and delivery vans. The ten acres behind the Brewery walls were still inactive, still waiting.

The decision that comes down from Whitehall will be written in the idiom of policies and paragraphs. On the street, it will be read more simply. Did the law side with those who own the land, or with those who live on it? Did it treat Brick Lane as a living neighbourhood, or as another square on a financial map of the city?

The microphones are off. The lives they briefly amplified continue.

Selected publication list for the theorists referenced

Brett Christophers

Christophers, Brett. 2020. Rentier Capitalism: Who Owns the Economy, and Who Pays for It? Verso.

Christophers, Brett. 2018. The New Enclosure: The Appropriation of Public Land in Neoliberal Britain. Verso. (Verso)

Christophers, Brett. 2019. “The Rentierization of the United Kingdom Economy.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space.

Manuel B. Aalbers

Aalbers, Manuel B. 2016. The Financialization of Housing: A Political Economy Approach. Routledge.

Aalbers, Manuel B. (ed.). 2012. Subprime Cities: The Political Economy of Mortgage Markets. Wiley-Blackwell. (Wiley Online Library)

Aalbers, Manuel B. 2008. “The Financialization of Home and the Mortgage Market Crisis.” Competition & Change.

Aalbers, Manuel B., and Brett Christophers. 2014. “Centring Housing in Political Economy.” Housing, Theory and Society 31(4): 373–394.

Loïc Wacquant

Wacquant, Loïc. 2023. Bourdieu in the City: Challenging Urban Theory. Polity Press.

Wacquant, Loïc. 2022. The Invention of the “Underclass”: A Study in the Politics of Knowledge. Polity Press.

Wacquant, Loïc. 2008. Urban Outcasts: A Comparative Sociology of Advanced Marginality. Polity Press. (Polity Books)

Wacquant, Loïc. 2009. Punishing the Poor: The Neoliberal Government of Social Insecurity. Duke University Press. (dukeupress.edu)

Wacquant, Loïc. 2006. Body & Soul: Notebooks of an Apprentice Boxer. Oxford University Press. (Oxford University Press)

C. Wright Mills

Mills, C. Wright. 1959. The Sociological Imagination. Oxford University Press. (Oxford University Press)

Mills, C. Wright. 1956. The Power Elite. Oxford University Press. (Oxford University Press)

Mills, C. Wright. 1951. White Collar: The American Middle Classes. Oxford University Press. (academic.oup.com)

Editorial Note

This report is a fair and accurate account of open proceedings at the Truman Brewery Public Inquiry, based on the official transcripts of 31 October 2025 and the parties’ published closing submissions for the appellants, the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, and the Save Brick Lane Rule 6 party.

Commentary and interpretation reflect the author’s independent analysis in accordance with NUJ and IPSO standards for accuracy, fairness and responsible journalism. This reporting is protected by qualified privilege under Schedule 1 of the Defamation Act 1996.