Day One: From Brick Lane to Rye Lane

Day One of the Aylesham Centre Inquiry exposed the architecture of London’s new planning economy — where regeneration speaks the language of renewal while operating as a system of financial extraction and class displacement.

Prologue: The Hearing Room and Its Geometry

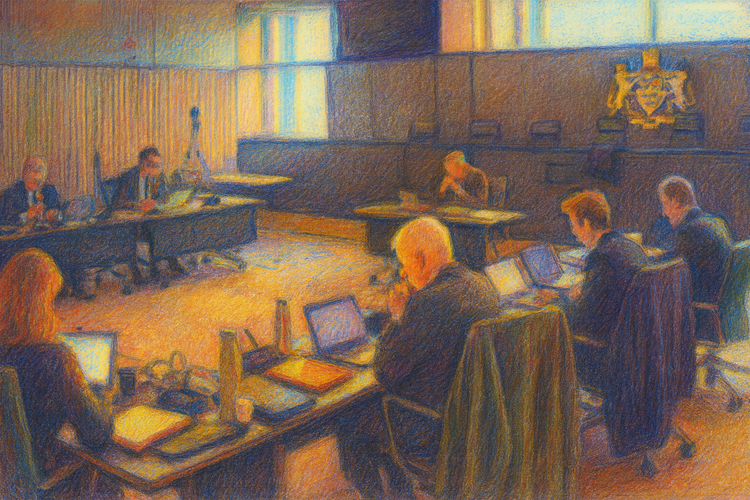

It is just after 9:30 AM on Monday, 27th of October 2025, and an extension room of Southwark Town Hall has been reconfigured for adjudication with four long tables facing one another across a narrow aisle. Microphones glow red; cameras streaming live to Southwark Council's portal. The soundscape is sterile — the hum of electricity, the shuffle of ring binders, the nervous coughs of an audience now part of the record.

At the centre of the room sits Inspector Martin Shrigley, appointed by the Secretary of State to determine Berkeley Homes’ appeal against Southwark Council’s refusal of planning permission for the redevelopment of the Aylesham Centre — a 1980s shopping mall at the heart of Peckham. His authority is procedural, total, and — as he reminds the hall — exercised “in the interests of fairness and openness to all parties.”

To his left, Russell Harris KC, representing Berkeley Homes, coordinates a team of planners, viability consultants, and design witnesses. Laptops open, he glances at the livestream camera before murmuring to his junior. Their documents bear the corporate blue of the Berkeley Group.

To his right, Richard Turney KC speaks quietly with planning officers and heritage advisers from Southwark Council. The Council’s case rests on defending a policy framework already tested for viability: a 35 percent affordable-housing target and a design brief for a mixed-use civic core.

At the far end of the hearing room, almost outside the frame, Hashi Mohamed of the Southwark Law Centre arranges notes on behalf of Aylesham Community Action (ACA) — the Rule 6 Party representing residents, traders, and faith groups.

Behind them, the public gallery fills with a cross-section of Peckham: shopkeepers, campaigners, clergy, local journalists, and councillors Jasmine Ali, David Parton, and John Batteson, each due to address the Inquiry later that day. From the start, the geometry of the room tells its own story. Those who own sit closest to the light; those who represent occupy the middle ground; those who live the consequences are placed at the edge. At 10:07 a.m., the microphones click live.

“We will proceed first with the Appellant’s opening statement,” the Inspector announces.

The choreography of Day One begins.

Prelude: The Rentier City

The Aylesham Centre Inquiry is not simply a test of planning law; it is a demonstration of market power. Behind the civility of the opening session lies a structure of ownership that now defines British urbanism: a small cohort of rentier developers — Berkeley Homes among them — who control not only land but the institutional circuits through which land becomes value.

Here, rentier capitalism is used in the sense developed by Brett Christophers (Rentier Capitalism, 2020; Our Lives in Their Portfolios, 2023), Manuel B. Aalbers (The Financialization of Housing, 2016), Guy Standing (The Corruption of Capitalism, 2016), and David Harvey (A Brief History of Neoliberalism, 2005). In their analysis, wealth no longer derives from production but from ownership — from the legal privileges and monopolies that allow assets to generate rent. Housing, under this logic, ceases to be shelter or social infrastructure; it becomes a financial instrument. Planning policy, far from restraining this process, functions as its enabling mechanism.

To understand who gains and who loses within this system, class must also be mapped. As Erik Olin Wright argued in Classes (1985) and Envisioning Real Utopias (2010), class in late capitalism is determined by one’s position within structures of ownership and control — not only who possesses assets, but who manages and legitimises them. Regeneration materialises this hierarchy in physical form. At one pole stand the rentier elites, owners of capitalised land and its debt instruments; at the other, the working-class residents and traders displaced by redevelopment; between them, a managerial-professional stratum — consultants, planners, and lawyers — whose role is to translate private accumulation into public legitimacy.

The Aylesham Inquiry hearing room makes the class diagram visible in real space: ownership seated nearest the Inspector, governance ranged opposite under fluorescent light, and community placed behind — present, but peripheral.

Theory in Context

Rentier capitalism (Christophers, Aalbers, Standing, Harvey) describes an economy organised around ownership rather than production; class analysis (Wright) explains how that ownership is enforced through layered control. In the Aylesham Inquiry, both frameworks converge: financial power operates through procedural neutrality, while class position determines who may speak and who is heard.

From Brick Lane to Rye Lane

From Brick Lane to Rye Lane, the same pattern repeats. On Day One, behind the language of a “community-led” masterplan stood a development consortium whose reach extended far beyond architecture. Financial institutions, law firms, marketing agencies, and political consultancies moved in coordinated sequence, supported by government frameworks and a growing archive of successful appeals. The public inquiry — ostensibly neutral — functioned as part of that infrastructure, a procedural stage in a larger choreography of legitimacy.

Behind the imagery of civic renewal lies a deeper transformation: the conversion of London’s market-based local economies into a digital-property model of productivity, displacing the restorative urbanism that once bound community, craft, and place.

The Peckham Experiment: An Opening

Every planning inquiry begins with gratitude.

“We believe in building homes… We welcome growth — but it must be the right kind of growth,” declared Cllr Jasmine Ali, her voice carrying across the chamber.

That distinction — the right kind of growth — set the tone for arguments over the future of the Aylesham Centre. What Berkeley Homes called “a transformational brownfield opportunity” the Council and community called “a missed opportunity of historic proportions.”

From the opening hour, the parallels with the Truman Brewery inquiry on Brick Lane were unmistakable: the same vocabulary — heritage-led regeneration, viability-tested affordability, public-realm enhancement — each phrase performing virtue while erasing substance.

Three Versions of the Same City

For the Appellant, represented by Russell Harris KC, Peckham was a “wasteland backland” waiting to be “re-activated.”

“The appeal proposals will remove the monumental, dead-eyed post-modern monoculture … and make full use of the wasteland backland of the site,” he said, promising “867 well-conceived homes across a masterplan of 16 buildings.”

For the Council, Richard Turney KC described a scheme “that falls well short of the aspirations for Peckham,” offering 12 percent affordable housing where 35 percent is policy.

For the community, Hashi Mohamed warned of “a generationally damaging change that will be irreversible,” linking every policy shortfall to human consequence: fewer family homes, lost small shops, and the erasure of Peckham’s “living, multicultural high-street economy.”

Together, these openings revealed a single crisis seen from different altitudes: at the top, a market logic framing viability as necessity; in the middle, municipal realism defending the plan’s integrity; at the ground, a community ethic insisting the plan was meant to defend them.

Heritage as Justification

On Day One, the word heritage circulated through the chamber like a token passed between hands, gathering a different meaning with each exchange. For Berkeley Homes, it was an instrument of persuasion — a language of reassurance designed to make demolition sound like care. Russell Harris KC spoke of a “heritage-led scheme” that would “repair the grain of Rye Lane” and “restore legibility to a tired town centre.” These phrases evoke stewardship and empathy, suggesting the developer as conservator. But when rendered into architectural form, repair translated as demolition; legibility meant the insertion of seven-storey façades whose bulk and repetition mimic — and then overpower — the three-storey rhythm they claim to honour. What was described as re-stitching the urban fabric amounted, in practice, to the replacement of history with its aesthetic echo.

For Southwark Council, heritage was a duty rather than a style. Its opening statement warned that the proposals would “obscure the historic sequence of buildings from which Peckham’s identity derives,” transforming the subtle variety of shopfronts, rooflines, and materials into a single corporate register. The Council’s case positioned heritage as part of the statutory framework — something to be protected, not re-interpreted at will.

For the community, heritage existed not in façades but in continuity: the small traders, congregations, and residents whose daily routines give the street its rhythm. Their appeal was for lived time — a form of memory inscribed in practice rather than design. As Hashi Mohamed put it, Peckham’s heritage “is a living, multicultural high-street economy, not a backdrop for speculative architecture.”

Between these definitions, Cllr Jasmine Ali offered the bridge and the warning:

“Growth must be rooted in community need, respectful of local character.”

Detached from that need, heritage becomes what Dr Anna Minton later called covert exclusion — the use of preservation language to legitimise privatisation. Day One thus reframed heritage as a battleground of ownership: for developers, a tool of branding; for councils, a legal standard; for communities, an assertion of collective memory struggling to remain visible.

Viability as Design Principle

In today’s planning logic, design begins with a spreadsheet. The Aylesham masterplan was no exception. From the moment the Appellant’s slides appeared on the monitors — bar charts in corporate blue, margins of yield and cost — it was clear that aesthetics would follow finance.

“Twelve percent affordable housing represents the maximum reasonable contribution at this point in the cycle,” Russell Harris KC insisted, transforming deficiency into virtue within a sentence. “This is a material public benefit.”

The claim condensed an entire economic model: rising construction costs, cautious investors, and a profitability threshold fixed between seventeen and twenty percent. Richard Turney KC, for the Council, replied sharply:

“The viability assessment must not wag the dog.” He reminded the Inspector that Southwark’s 35 percent target had been tested through plan-making, not invented in abstraction. Re-defining it through proprietary modelling, he argued, “hollows out the plan itself.”

For Aylesham Community Action, the issue went deeper than arithmetic. Their analysis demonstrated how financial assumptions — debt ratios, inflation forecasts, the treatment of supermarket re-provision as cost rather than asset — were calibrated to minimise affordable output. What appeared as mathematical inevitability was, in truth, discretionary arithmetic: policy arbitrage rendered in Excel.

The wider implication was unmistakable. Viability, a term that sounds empirical, now functions as an ideology: a device for translating political choices into technical necessities. Once invoked, dissent appears irrational — who can argue with “what the numbers show”? And yet, as one ACA witness observed, “Every ten homes removed from the affordable quota represents ten families displaced.” In the calculus of deliverability, those families become an immaterial difference — a rounding error in a spreadsheet that measures risk, not consequence.

Public Realm and the Politics of Inclusion

If viability is the engine, public realm is the display window — the visible promise through which financialised development presents itself as civic virtue. Berkeley’s design documents spoke of “open and accessible routes,” “civic squares,” and “active frontages.” On Day One, these phrases sounded benign — the language of generosity — until the witnesses unpacked their meaning.

Dr Anna Minton reminded the Inspector that Peckham’s distinctiveness rests on genuinely public space: the market stalls spilling into pavements, the informal mixing of music, worship, and trade. Her statement warned that the scheme would replace this culture with privately owned public space (POPS) “characterised by uniformed security, defensible architecture, and restrictions on behaviour — including photography, protest, and informal play.”Each of these, she explained, is a mechanism of control disguised as design. What looks like openness often enforces compliance; what appears safe often excludes.

Sarah Goldzweig, representing Latin Elephant, provided empirical weight.

All traders facing displacement, she noted, are from migrant or racialised backgrounds, repeating a pattern seen at Elephant & Castle, where “relocation funds proved insufficient and unfulfilled.” To her, the Aylesham proposals extended a geography of exclusion across South London: the enclosure of public life through the language of design.

In the afternoon session, Rev Dean Pusey, vicar of St Mary Magdalene, shifted the argument from policy to ethics:

“We risk creating a dormitory suburb serving wealthier members in the two epicentres of our capital — the City and Canary Wharf.” He called the project “social engineering by architecture,” a phrase that hung in the air long after he sat down.

Finally, Janine Below, a lifelong resident, voiced what many felt:

“This development will rip out the beating heart of a tight, energetic, culturally diverse community … you wouldn’t know if you were in Lewisham or the Truman Brewery.”

Each of these testimonies re-defined public realm not as an architectural component but as a condition of belonging — the right to remain visible, audible, and present in one’s own city. Day One made clear that where developers imagine activation, residents anticipate exclusion; where design drawings promise openness, lived experience foresees control.

Democracy by Inquiry

The Inquiry promises to hear evidence, but it also performs legitimacy. Its very architecture — the stage-managed order of proceedings, the fixed seating plan, the neutral vocabulary of law — converts civic participation into ritual.

The order of speaking enacts a hierarchy that mirrors the system it claims to scrutinise: the developer first, armed with consultants, graphics, and case law; the council second, equipped with policy references and procedural caution; the community last, constrained by time limits and the polite choreography of deference. To watch the sequence unfold was to see planning hierarchy made visible — the pyramid of capital, governance, and local life stacked in real time.

When Inspector Martin Shrigley interjected,

“Policy weight is not afforded to sentiment,” his tone was patient, factual — a reminder to witnesses that emotion carries no statutory value. Yet in that procedural neutrality lay the quiet violence of the system: only what can be measured counts; only what fits within the template of policy is heard.

What the rules call fairness can feel, to those seated furthest from the microphone, like abstraction masquerading as justice. Testimony rooted in lived experience — the cost of rent, the erosion of space, the loss of community networks — becomes immaterial evidence, untranslatable into planning weight.

And yet, Day One was not without disruption. Moments pierced the surface:

- Dr Anna Minton’s phrase “covert exclusion” landed with academic precision but moral force, recasting urban design as a regime of control.

- Sarah Goldzweig’s recollection of the Elephant & Castle traders drew murmurs from the back rows — a recognition that what was being debated in Peckham had already been lived elsewhere.

- Janine Below’s warning that “you wouldn’t know if you were in Lewisham or the Truman Brewery” broke through the procedural calm; for a second, the chamber sounded like a neighbourhood, not a courtroom.

Each of these interventions was brief, fleeting, yet vital — fissures in the performance through which lived reality entered the record. They reminded everyone that transcripts are not experience but its bureaucratic trace — that democracy, when channelled through inquiry procedure, survives only as an administrative memory of dissent.

The Meaning of Regeneration

By the end of Day One, one word had echoed more than any other: regeneration. It appeared in opening statements, in design proofs, in policy cross-references, and even in the day’s press release from the Appellant’s communications team. But the repetition revealed fracture rather than consensus.

For Russell Harris KC, regeneration meant activation and pace.

“This is a major regenerative opportunity for South London — a chance to transform a redundant site into a vibrant new quarter.” Here, regeneration was performance: a metric of delivery, a promise of scale, a synonym for profit.

For Cllr Jasmine Ali, the same word carried the opposite charge.

“It must be the right kind of growth — rooted in community need, respectful of local character.” Her definition spoke to repair — the slow labour of social reinvestment and stability — against the velocity of speculative capital.

Between these two registers lies the central contradiction of London’s planning politics: regeneration as renewal versus regeneration as yield.

In practice, the numbers told their own story. The share of affordable housing had fallen from 35 to 12 percent; the Community Land Trust tenure, once a condition of allocation, had been deleted; 3,500 square metres of retail floor space — much of it occupied by long-standing independents — would vanish. Yet the scheme’s profit margin remained constant. Regeneration, in this calculus, is no longer a civic ideal but a financial algorithm: the reclassification of extraction as benefit, displacement as progress.

Rev Dean Pusey’s voice cut through that logic with a question that drew silence from the gallery:

“What is being regenerated if the people who made Peckham what it is can no longer afford to live here?”

It was a question the Inspector could not answer; it fell outside material considerations. But it distilled the moral truth of Day One: that the term regeneration has been severed from its social roots and refitted to serve financial architecture. Once a word for collective renewal, it now names the process by which communities are displaced in the name of their own improvement. What began as a promise of inclusion has become the grammar of managed exclusion — the civic dialect of the rentier city.

Epilogue: Brick Lane to Rye Lane

From Shoreditch to Peckham, the geography of regeneration has shifted, but the hierarchy it enforces has not. Day One laid bare a city divided by class and economy: on one side, the working-class and migrant networks of everyday trade and tenancy; on the other, the digitised, financialised property machine that converts neighbourhood life into income streams.

In Erik Olin Wright’s terms, this is the lived structure of class in late capitalism — rentier elites extracting through ownership, a professional-managerial layer legitimising the process, and a dispossessed urban class experiencing “regeneration” as displacement.

For now, the machinery of extraction still writes London’s planning language. Yet resistance — legal, civic, cultural — grows more articulate with every transcript. Peckham is not merely a site; it is a record — a living document of London’s struggle to decide what regeneration, democracy, and class belonging truly mean.

Editorial Note

This report is a fair and accurate account of open proceedings at the Aylesham Centre Public Inquiry (Day 1, Opening Session) and is protected by qualified privilege under Schedule 1 of the Defamation Act 1996. Commentary and interpretation reflect the author’s analysis, written in accordance with NUJ and IPSO standards for fair, accurate, and responsible public-interest reporting.

Quotations are drawn from the public recording and from hearing notes taken by this reporter, and are reproduced within the context of fair reporting and public record.