Day 9 – Light, Language and the Right to Remain

Brick Lane Inquiry, Morning Session – Tower Hamlets Town Hall

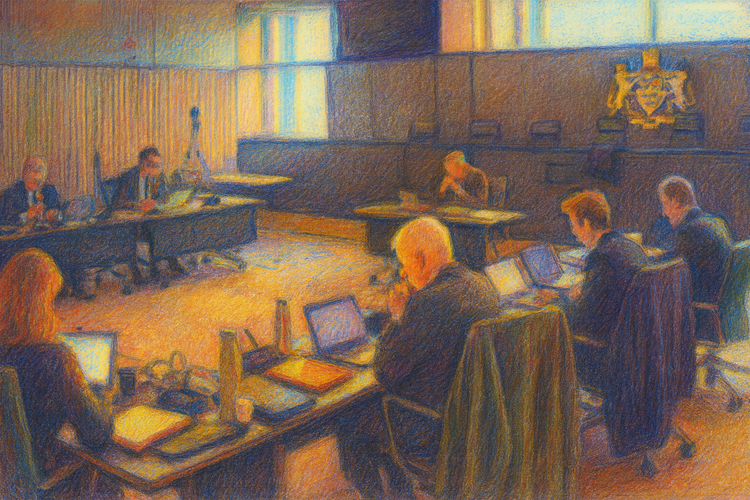

By the ninth morning of the Truman Brewery Public Inquiry, the room had changed but the fault-lines had not. The hearing had moved from the purple raked seats of the Brady Arts Centre to the high-ceilinged chamber of Tower Hamlets Town Hall, the borough crest watching over a horseshoe of desks and glowing laptop screens.

The layout, though, was eerily familiar. To the Inspector’s right sat the Appellant’s team; to his left, counsel and officers for the London Borough of Tower Hamlets; opposite him, at the far side, the Rule 6 Party Save Brick Lane. Behind them, in the gallery, residents, campaigners and observers watched as one more day of evidence tried to decide the future of a ten-acre site that has long been part of their lives.

In earlier reports in this series, we followed how the Inquiry turned on design and policy: the “architecture of justification” built around Block A, the windowless data centre on Grey Eagle Street; the struggle over “heritage-led” regeneration; the emergence of rentier capitalism as the invisible client. Day 9 brought something different back into focus: the basic conditions of inhabiting a city — light, language, memory, the right to stay put.

I. Michael Ball (Just Space): Daylight, Allen Gardens and the Weight of Harm

The morning opened not with a planner or developer, but with Michael Ball, speaking on behalf of Just Space, a long-standing network of community organisations that intervenes in London planning when policy drifts away from lived reality.

“I don’t live anywhere near here,” he began, “I live in Lambeth, but I have come representing Just Space.” His evidence, he stressed, was independent: he had advised Save Brick Lane on how to present technical material but was not part of their Rule 6 case. His subject was daylight — not as a specialist consultant, but as someone who had “secured the services of the BRE on three occasions” in previous inquiries where access to light had become a deciding issue.

Ball’s starting point was deceptively simple: in the Statement of Common Ground, the main parties agree that daylight and sunlight are “acceptable”, even while acknowledging “significant failures” in the social rented homes. That paradox, he suggested, mirrored other London cases such as 8 Albert Embankment, a called-in inquiry where both council and developer had signed off the metrics — only for the Inspector and Secretary of State to give “very significant weight” to the resulting gloom in affordable housing and to refuse permission in part on that basis.

Ball then walked the Inquiry through the policy hierarchy. London Plan D6 requires development to provide “sufficient daylight and sunlight” to new and surrounding homes; the Housing Design SPG and Local Plan policies, including Tower Hamlets’ D.DH8, pull those principles down to borough level. Crucially, the Local Plan does not treat BRE guidance as optional: it refers explicitly to it as the “most current guidance” for assessing daylight.

From there, he turned to the Environmental Statement’s own numbers. Forty-five per cent of assessed windows around the masterplan site currently receive at least 27% vertical sky component (VSC) — a surprisingly high level for such a dense inner-city area. In the Environmental Statement’s Woodseer Street consent scenario, that figure falls to 39.5%. The headline might sound technical; the lived effect is not. Where VSC falls below 27%, the BRE’s own summary warns that rooms become progressively harder to light: between 15–27% “special measures” such as larger windows are needed; below 15% “it is very difficult to provide adequate daylight”; below 5% it is “often impossible.”

At 20 Calvin Street, the ES itself concedes a “direct, permanent, long-term adverse effect” on daylight, classed as “moderate adverse.” Ball unpacked what “moderate” means in this context: any loss above 20% is “significant and noticeable”; 20–30% is labelled “minor adverse”, 30–40% “moderate”, and above 40% “major”. “Moderate” here is a technical bucket, not a reassurance. In plain language, half the rooms modelled in one of the scenarios would experience losses beyond BRE guidelines.

The heart of his evidence, though, lay not in Calvin Street but McGlashon House, the slab of social housing that faces the proposed massing across private gardens and trees. Under the appeal scheme, 132 of its 271 windows would fail the BRE test; 120 would be left with VSC below 15%, which the guidance describes as “pretty gloomy”. The Environmental Statement calls this impact “moderate adverse” and moves on. Ball did not:

“This is a block of affordable housing. The tenants do not choose to live here. They cannot trade off benefits of living here against very gloomy living conditions. Material reductions in daylight should not be set aside lightly. Significant weight should be attached to the harm caused to the occupiers of this building.”

He tied the point back to the Albert Embankment decision, where the Secretary of State agreed that residents in nearby affordable blocks would experience an “unacceptable increase in gloominess” and attached “very significant weight” to that harm. The message for Brick Lane was clear: when the people most affected have no housing choice, daylight is not a marginal comfort factor; it is part of the minimum conditions of urban citizenship.

The same logic governed his analysis of Allen Gardens, the small park that sits north of the Truman site. Tower Hamlets’ Open Space Strategy records borough-wide open space at 0.89 hectares per thousand residents — already below the 1.2 ha standard — and identifies Spitalfields and Banglatown ward at just 0.3 ha per thousand, one of the most deficient in the borough. In that context, Ball argued, BRE and London Plan guidance on overshadowing are not technical niceties but a safeguard for the only local green space.

Looking at the Appellant’s December shadow diagrams, he noted that the winter sun-paths across Allen Gardens literally run off the page: the modelling sheet ends before the full length of the shadow is shown. What it does show is that “all of that part of Allen Gardens directly to the north [of the site] is in shadow, permanent shadow throughout the winter.” This, he reminded the Inspector, is contrary to GLA Housing Design Standard B9.5, which says spaces designed for frequent use — including sitting and play areas — should receive direct sunlight through the day, particularly in winter.

Ball did not ask for refusal on daylight alone. “This is an issue of weight,” he said. “I’m not suggesting that the scheme should be refused on the issues of daylight, but… there needs to be considered weighting of the daylight problems with this scheme.” In a hearing already saturated with metrics, his evidence did something quietly radical: it reframed daylight as a question of distributive justice. Whose windows are allowed to go dark so that a speculative data-centre campus can rise?

From there, the morning shifted from quantified light to articulated experience.

II. Stephen Watts – Language, Memory, and the “Rich Rich Culture”

Next came Stephen Watts, poet, archivist and long-time resident of the East End.

“I’m a poet,” he said simply. “That position was precisely where… I have performed my poetry, where some of the great poets of Bangladesh… have performed their poetry… That is what place means.”

Watts spoke less about bricks and massing and more about continuity. Brick Lane, he said, is “a vibrant, astonishing place… a place of rich continuum of language and languages.” If you stand on the street and think how many tongues have been spoken there over centuries — “even in the course of the past ten years” — you begin to grasp what is at stake when redevelopment treats the area as a blank slate.

He traced a lineage of writers who crossed Cheshire Street and Allen Gardens into Brick Lane — Avram Stencl, Rachel Lichtenstein, Emmanuel Litvinoff, Iain Sinclair, Shamim Azad, Milton Rahman — before recalling that his first poem about the area was written “in the aftermath of the murder of Altab Ali in the late nineteen-seventies.” Had Ali not been murdered, Watts reflected, “he would have been of an age of those elders who you heard last Tuesday” — a reminder that the anti-racist struggles of Whitechapel are not heritage motifs but living memory.

Watts concluded with a quiet rebuke to the week of technical evidence:

“For all the important things that have been said… there have been an almost oblivious absence of statements, namings, and what I’ve just talked about… Brick Lane is a rich rich culture and it’s also a place of astonishing struggle.”

Where earlier days had seen heritage reduced to façade lines and view cones, here it appeared as a lattice of language, struggle and solidarity. The question was no longer whether the scheme was “heritage-led,” but whether it could even see the heritage it was about to overwrite.

III. “This Isn’t Just About Urban Planning” – Suad Chantouki and Walaa Abdelbaky

If Watts restored memory to the record, Suad Chantouki restored politics.

“Good morning, everyone,” she began. “This isn’t just about urban planning — it’s about who gets to shape our community and who gets left behind.”

Brick Lane, she reminded the Inquiry, “isn’t just a place on a map; it’s a living history. Generations of migrants have built families, opened businesses, and turned this corner of London into a symbol of resilience and community. The Huguenots, Jewish tailors, Bangladeshi workers — each wave of settlement has added a new chapter to this story. But that story is now being rewritten — and not by us.”

Her own housing situation illustrated the stakes: six adults crowded into a small flat, constantly negotiating space, air, sleep. Another resident, Walaa Abdelbaky, described living with a husband who suffers asthma attacks in a mould-tainted home:

“When he has an attack he needs to breathe fresh air, but the whole house is mouldy and we need to go outside… We haven’t space to put our books or to study… We can stay three of us in the hall and two of us in the bedroom… If my husband is feeling any problem in the night… I want fresh air for him. But… my child is sleeping. I can’t open the door. I haven’t the space. We have to go out into the street.”

Her conclusion was as direct as any planner’s recommendation:

“If you want to change Brick Lane and make all of Brick Lane shops, I’ll be happy, it’s all right. But before that, please, give me a house. Just this.”

In a hearing where the Appellant’s case hinges on the notion that the data centre and new offices are a “public benefit”, these statements quietly inverted the calculus. The benefit foregone was not speculative tech employment but habitable space to live.

IV. “We Stayed” – Councillor Suluk Ahmed and the Right to Remain

The morning’s political spine came from Councillor Suluk Ahmed, representing Spitalfields and Banglatown ward.

“My name is Councillor Suluk Ahmed, and I am proud to represent Spitalfields and Bangla Town Ward,” he began. “Most importantly, I am a resident of the Brick Lane area — the very heart of our community.”

He traced a family history that paralleled the street’s modern era. His father, Shamuz Ali, “a tailor by profession, chose in the early 1960s to set up his leather garments manufacturing business here in Brick Lane… I have spent nearly 50 years of my life here… I have six children also living with me.”

The community, he reminded the Inquiry, had not arrived into comfort:

“We suffered racism from many directions: from neighbours, the police, schools, colleges, and on the streets. But despite all of that, we stayed. We worked hard. We contributed to the area’s growth, and we helped make Brick Lane and its surroundings the vibrant, diverse, and cultural place it is today.”

Now, after decades of struggle, “we deserve better housing and the opportunity to continue living side by side — in peace and dignity.” The implication was clear: a scheme that intensifies commercial pressure while delivering almost no social housing is not regeneration but amnesia.

V. The Generational Voice – Mikael and Jahed Ahmed

The session also heard from younger voices carrying the burden of continuity.

One statement, read by Mikael Ahmed, described Brick Lane through the experience of his autistic younger brother:

“My little brother… loves this place. The energy here, the people, the sounds of the market, it’s what makes him feel calm and collected… The street is familiar to him… He shouldn’t have to worry about the place he loves being taken away from him.”

Development here was not an abstraction in a design and access statement; it was a threat to the only environment in which a vulnerable family member feels at home.

“We risk losing everything that matters,” the statement continued — “the local businesses, the artists, the families. They are the heart of this community… Don’t let Brick Lane be changed for the few at the expense of the many… A place for everyone, not just the rich.”

Later, Jahed Ahmed situated the scheme against his own childhood landscape. Growing up in McGlashon House with seven siblings and parents, their balcony “overlooked the Truman land area… Besides that there’s a little green area called Allen Gardens. We used to play football there… Sometimes the ball went over the wall into the Truman area… We climbed that wall. We shouldn’t have, it was dangerous, but we did.”

The anecdote carried more than nostalgia. It recalled a time when Truman’s land and Allen Gardens formed a porous landscape, not the enclosed “campus” imagined in the masterplan. Where the Appellant’s design language emphasises controlled squares and curated yards, Jahed’s memory recalled improvised permeability — a civic commons of kids, park, and factory wall.

VI. “Corporate-Led Gentrification” – Kleinberg’s Frame (Read by Jonathan Moberly)

If earlier pieces in this series read the Inquiry through Mills, Jacobs and Christophers, Day 9 brought its own theorist to the table in the form of Gabrielle Kleinberg, who holds an MSc in Regional and Urban Planning Studies from LSE. Her written statement was read into the record by Save Brick Lane organiser Jonathan Moberly.

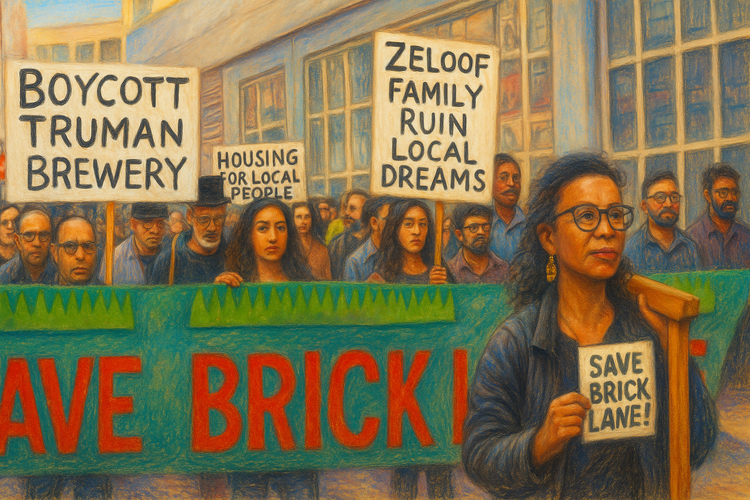

Brick Lane, Kleinberg argued, has moved from being “the geographical signifier of racial strife in the East End” to experiencing “a more covert and insidious form of racialized violence: corporate-led gentrification.” Here, gentrification is not just demographic churn but “a reconfiguration of the street’s cultural heritage into a consumable, marketable spectacle.” The Truman Brewery, in her account, “capitalise[s] on the historical character of the street and curate[s] their own environment where diversity and creativity are selectively incorporated so long as they do not threaten their bottom line.”

She recalled first walking north into the Truman-dominated end of Brick Lane — “a land of overpriced secondhand clothing” — before discovering, on the return journey south to Whitechapel, that the street is also “an enclave of organically-produced culture… what living in cities is all about… a perfect example of Lefebvre’s production of space.”

Kleinberg’s statement dissected Truman’s “false authenticity”: curated markets, sanctioned street art, food halls like Upmarket, all catering to “the heterogeneity of urban villagers and taste cultures” while being “imposed top-down for the sole purpose of making money… and as Lefebvre predicted: it’s boring.” Even protest, she noted, is commodified — a shop inside the estate sells a book titled The Art of Protest while the Brewery threatens legal action when its own dominance is challenged.

Her sharpest warning concerned ownership and infrastructure. Truman and the Zeloof family have trademarked “Brick Lane” across dozens of product classes, signalling an ambition to become the “hegemonic cultural meaning-maker” for the street. At the same time, London’s “AI rush” is being used to justify a local data-centre cluster that lands hardest in Tower Hamlets:

“This crisis, we all know, is the housing crisis… Kensington has zero data centres. Westminster has one. Why should the most densely populated borough in London be the one with over 30? Why must the most marginalized people in our city be forced out by speculation-based real estate?”

If the scheme proceeds unchecked, she argued, it will “further marginalise the British-Bangladeshi community to the fringes of the city.” But if the Inquiry stands for accountability and listens to those who “LIVE in Brick Lane, not those who see the street as an asset portfolio rather than a shared home,” Brick Lane could become a model for regeneration “produced, not imposed.”

“Please do not let Brick Lane, a place that has always stood for resilience and resistance, turn into a monument to exclusion.”

Other speakers filled in the everyday texture behind those headline testimonies. Asma Rukia Ahmed, Rim Moustafa, Shilpa Akher, Shamsun Chowdhury, Ayrun Begum and Shah Rayhan Uddin all described versions of the same predicament: overcrowded flats with no lifts, damp and mould that trigger asthma, families sharing single toilets and improvised bedrooms, children trying to do homework in corridors or hallways while parents work late shifts. Several warned that rising commercial rents and chain-store expansion were already pushing out independent traders; others pointed to relatives who had spent years on housing lists while speculative schemes multiplied around them.

Their collective message to the Inspector was disarmingly simple:

Before more offices and a data centre are approved, Brick Lane’s communities need secure, affordable homes and protection for the small businesses that keep the street alive.

VII. The Planner in the Dock – Marginson Revisited

When the public statements ended, the Inquiry pivoted back from lived experience to policy. Jonathan Marginson, the Appellant’s planning witness, returned to the table — this time under cross-examination from Richard Wald KC for the Council. Wald’s opening questions were simple: had anything he had heard in the preceding days caused him to rethink his conclusion that an employment-led scheme was the correct outcome for the site? Marginson’s answer was equally simple: “No.”

Wald then rebuilt, piece by piece, the policy context that Marginson had treated as settled. Starting from the NPPF and the London Plan, he reminded the room that Tower Hamlets is “more acutely in need of housing than any other borough in London,” and that policy requires decision-makers to “deliver the homes Londoners need,” including an appropriate mix for local communities. Marginson accepted each point, and agreed that these policies are plainly relevant to the possibility of a residential-led scheme on the Truman site.

The cross-examination then turned to the development plan itself. Wald put it to Marginson that, taken as a whole, the London Plan and the Tower Hamlets Local Plan “pull in both directions” — towards employment and towards housing — and that any planner must weigh those directions in the round. Marginson agreed that “there are policies that pull in each direction,” but maintained that, in his judgment, they add up to support for an employment-led scheme. What Wald’s questions exposed, however, was that this was a choice, not a command: nothing in the plan requires the Truman site to be used for a data-centre-anchored office campus rather than for housing.

Finally, Wald brought the argument back to place. Using Marginson’s own figures, he contrasted the Truman land with the “very intensive commercial” cores of Bishopsgate and Spitalfields, pointing out that the streets east and north of the site are overwhelmingly residential. Marginson resisted neat labels but ultimately accepted that the appeal site sits on the edge of dense housing and scarce open space, in a borough under exceptional housing pressure.

The cross-examination joined biography to structure: the overcrowded flats and overshadowed parks described by residents are not accidents at the margin of policy, but the direct consequence of a planning judgment that keeps choosing commercial floorspace over homes.

VIII. From Metrics to Memory: What Day 9 Adds to the Record

Seen through C. Wright Mills’ lens, Day 9 was a textbook example of the “sociological imagination” at work: private troubles — mouldy flats, darkened living rooms, autistic children needing familiar streets — made audible as public issues. The evidence of Michael Ball translated the scheme’s massing into a ledger of gloom and lost winter sun; the voices that followed translated policy failure into biography and lineage.

Taken with earlier sessions — the critique of “heritage as commodity” on Day 2, the “heritage that matters” on Day 5, the exposure of rentier digital infrastructure on Day 7 — this morning did something the scheme has never quite managed: it joined up light, land and life. The same urban logic runs through each:

- A masterplan that builds right up to the boundary line, dimming social housing and overshadowing the only local park;

- A commercial strategy that treats Brick Lane’s cultural history as a brand asset;

- A data centre that functions less as utility than as rent-bearing infrastructure in a borough already over-supplied with such facilities;

- A housing crisis in which residents ask, simply, to “give me a house” before granting more floorspace to shops and servers.

The Inquiry cannot, by itself, resolve London’s structural inequalities. But it can decide whether this particular ten-acre site will deepen them or begin to repair them. Day 9 made it harder than ever to pretend that the decision is about architecture alone.

Editorial Note

This report is a fair and accurate account of open proceedings at the Truman Brewery Public Inquiry and is protected by qualified privilege under Schedule 1 of the Defamation Act 1996. Commentary and interpretation reflect the author’s independent analysis in accordance with NUJ and IPSO standards for accuracy, fairness and responsible journalism.