Day 9 (Afternoon) — Need, Weight, and the Test of “Good Growth”

Prologue – After Capital as Client, Back to the Planner

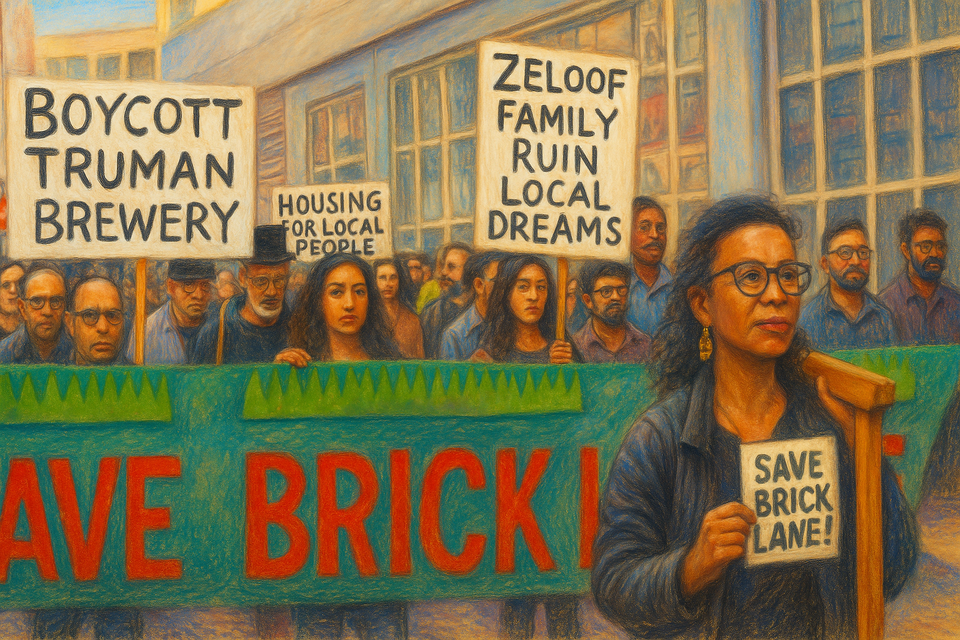

By the time the Inquiry reconvened after lunch on Day 9, the room had already heard most of the story. Day 8 had shown how the Truman scheme sits on the fault-line between financialised redevelopment and democratic legitimacy; “planning” appeared as a kind of public alibi for private logic. Day 9’s morning session had then brought residents and councillors to the forefront, turning light, language and overcrowding into a ledger of harm that the Secretary of State will now have to read.

The afternoon brought the planner back. Jonathan Marginson, the appellant’s planning witness, resumed his place at the table — no longer led gently through policy by his own counsel, but tested by Richard Wald KC for Tower Hamlets and Flora Curtis for Save Brick Lane. Once again, the question was not simply what the scheme proposes, but who gets to define need, measure benefit, and decide whose troubles count as “material considerations”.

If Day 8 framed the data centre as a valuation event — a device for re-rating land and anchoring global capital — Day 9’s afternoon session showed how that event is translated back into planning language: “need”, “weight”, “good growth”. What followed was less a clash of facts than a clash of priorities, set out in the polite grammar of cross-examination.

I. Offices in a Borough that Needs Homes

Wald opened on familiar ground: the Employment Land Review (ELR), a March 2023 document that charts supply and demand for office space in Tower Hamlets. Its opening pages describe a borough that has already experienced “many years of rapid growth” in office stock, followed by a recent decline. Even so, the pipeline remains vast: about 1.3 million square metres of corporate office floorspace already consented or under construction, several times the projected net additional demand. On the ELR’s own numbers, there is “no need to plan” for more large-floorplate corporate offices over the plan period.

Marginson did not dispute that picture. The oversupply of big-box City and Canary Wharf floorplates is common ground. His focus, instead, was on the exceptions: the ELR’s warning that, within this overall “picture of plenty”, there may be acute shortages of smaller units for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). That passage has become central to the appellant’s case. Where the borough-wide data shows excess, the Truman site is re-scripted as a local remedy — a bespoke SME hub that could soak up unmet demand in a “micro market” of creative, media and tech firms.

Wald’s questions pushed on the gap between those two scales. The ELR is clear about the oversupply of large corporate offices. It is more cautious about SMEs, using language of possibility rather than certainty: there may be shortages of certain types of small-unit space; the evidence is less settled. Marginson accepted that description. The demand for SMEs, he agreed, is “less sure” than the oversupply of bigger units — a point he then attempted to buttress with private agent reports and a bespoke consultancy note arguing that the Truman Brewery constitutes a unique sub-market, not easily substituted elsewhere.

Standing back, the contrast is stark. On the one hand, an equivocal assessment of SME demand, grounded in a single paragraph of a borough-wide study and then amplified by paid-for market advice. On the other, a housing position that is not equivocal at all. As Wald reminded the Inquiry — and as the morning session had already underlined —

Tower Hamlets is, by the appellant’s own concession, “more acutely in need of housing than any other borough in London”.

The planning framework “pulls in both directions”: towards employment and towards housing. But in Marginson’s balance, the direction of travel is clear. The scheme’s 44 homes, including six at social rent, are acknowledged and then quickly overshadowed by the promise of flexible SME workspace and a 3MW data centre. The ten-acre site is treated primarily as an opportunity to fix a possible future shortage in a niche office sub-market, rather than to address an existing, documented crisis in habitable space.

What Day 9’s afternoon exposed, in other words, was not a neutral reading of policy but a choice of emphasis: equivocal SME need is elevated; acute housing need is recognised, then subordinated. The development plan may allow such a choice, but it does not require it — a distinction that will matter when the Secretary of State weighs the same documents with a different audience in mind.

II. “Heritage-Led” by Edit: QRP and the Missing Morning

From there, Wald turned to another of the appellant’s anchor phrases: the claim that Truman’s masterplan is “heritage-led”. It is a phrase that has travelled through the Inquiry like a badge — invoked by heritage witness, architect and planner alike, and already unpicked in earlier reports on Days 2 and 6.

Marginson’s written proof relies heavily on the March 2024 Quality Review Panel (QRP) as evidence of that heritage leadership. In a key paragraph, he summarises the panel’s comments as endorsing a scheme that “celebrates” the Brewery’s history and responds positively to iterative design changes. Those bullet points, Wald established, are all drawn from the afternoon (PM) session of the QRP — a session that, on its own terms, was indeed upbeat. Panel members described the level of investigation as “one of the best seen at QRP” and looked forward to seeing the project come forward.

What is missing from Marginson’s summary is the morning (AM) session on the same day. Under questioning, he accepted that the AM meeting contained a series of unresolved concerns: about Cooperage Passage still feeling like a service corridor; about the uniform height of blocks facing Allen Gardens; about the massing within the conservation area; and about the lack of residential frontage and passive surveillance along the park edge.

Asked why none of this appears in his proof, Marginson first suggested that he had focused on the PM summary; then, after some exchanges, conceded that he “should have” included the AM material as well. “It’s not a reason to exclude it,” he admitted, before insisting that he had nonetheless taken a “balanced approach” in his own mind.

The problem, as Wald pointed out, is not what exists in the witness’s head but what appears in the public record. Without the AM session, the QRP is presented as a chorus of appreciation, not a collage of approval and unease. Without the list of reservations — on height, frontage, Allen Gardens, residential overlooking — the phrase “heritage-led” floats free of the very tensions the panel tried to register.

For anyone who followed Day 6’s evidence on “heritage-led” design, the pattern is familiar. There, too, the Inquiry heard how heritage guidance could function as a procedural shield: cited, acknowledged, and then used to certify a design whose core moves were made before any written heritage advice was in place. Here, the QRP plays a similar role. Its existence validates the process; its most positive comments are extracted as proof of success; its remaining doubts are left in the background, available to the Inspector but absent from the advocate’s narrative.

In a series that has already argued that “heritage as commodity” turns a living district into a brand, the QRP exchange adds a further nuance: heritage as edit. Not just which buildings are kept or lost, but which paragraphs are carried forward into evidence. The masterplan may or may not be heritage-led in substance; what Day 9’s afternoon made clear is that it is certainly heritage-led in presentation — curated through omission as much as through design.

III. Micro-Facility, Mega-Weight: The Data Centre Question

If the Employment Land Review exposed a choice about offices and homes, the next exchange made visible a different kind of inflation: how a 3MW data centre at Truman is being lifted into the same category as schemes more than thirty times its size.

At the start of this section, Wald took Marginson to a bundle of four Secretary of State decisions on recent data-centre appeals: Woodlands Park 1 and 2, Bedmond Road and Court Lane, Iver. None is small. One provides a 90MW facility; another, 96MW; the largest, 147MW, in buildings of 65,000–163,000 square metres — compared to 5,200m² and 3MW at Truman.

The exercise was simple. In each of those decisions, Wald pointed out, the need for data-centre capacity and the contribution made by the scheme was recognised and given significant weight. The Woodlands 2 decision explicitly describes the facility’s 90MW provision and the Secretary of State’s conclusion that “need should be given significant weight” in the balance; Bedmond Road similarly records that an 84,000m², 96MW scheme would provide around 3% of forecast growth in London’s capacity — yet, again, need attracts no more than significant weight.

On Wald’s “broad numerical comparison”, that 96MW/3% relationship implies that a 3MW facility like Truman’s Block A contributes roughly 0.09% of the same growth — “less than a tenth of a percent.” Marginson didn’t quarrel with the arithmetic. What he did dispute was the idea that contribution and weight were linked. Despite the Secretary of State’s practice in each of the four decisions, he insisted that in this case the data centre’s benefits warranted very substantial weight — the top rung in his own scale, above “significant”.

Pressed on this discrepancy, Marginson floated a theory: perhaps “significant” in those decision letters is already the top of the Secretary of State’s internal ladder, “lifted directly out of the NPPF”. Wald countered with the Woodlands 1 decision itself. There, paragraph 8 of the Secretary of State’s reasoning refers not only to matters of “significant” weight but also to multiple elements carrying substantial weight, establishing a clear hierarchy between the two terms. In other words, the language the appellant treats as a ceiling is, in fact, somewhere in the middle of the Secretary of State’s own scale.

When the comparison turned to Mulberry Place — a previous Harris-led data-centre case where counsel had argued that a 40MW extension represented a “unique benefit” sufficient to outweigh heritage harm — the symmetry became harder to ignore. The same advocate who once emphasised megawattage as a differentiator now relies on a planning witness who refuses to adjust weight for scale at all. Marginson told the Inquiry that there would be “no reason why a 5 megawatt scheme couldn’t be given the same weight as a 200 megawatt scheme… particularly where that is located on the edge of the City of London,” before correcting himself to 3MW.

Throughout, he leaned on Ms McGinley’s evidence: Truman’s data centre, he said, is a different “kind of need” — a retail colocation facility serving City financial functions, not a hyperscale cloud shed off the M25. But there is no published optioneering study in evidence, no documentary trail of alternative sites explored and rejected. Tower Hamlets’ own officers, in the report at CD L02, go so far as to note an “established cluster of large-scale data centres” at the edge-of-London locations cited in precedent, and to say there is “no compelling justification” that Block A’s specific configuration at Truman is uniquely critical.

In that light, the elevation of a 3MW plant to “very substantial weight” looks less like a conclusion compelled by national policy than a discretionary upgrade — one that sits uneasily alongside the Secretary of State’s own recent practice. If Day 8 framed the data centre as a valuation event, Day 9 afternoon showed how far the planning language around that event can stretch in order to keep its weight on the scales.

IV. Consultation Without Comprehension, Again

Where Wald’s questions probed the inflation of infrastructure weight, Curtis’s cross-examination returned to a theme that has run through the Inquiry since Day 8: consultation as appearance rather than access.

Curtis began with the borough’s own numbers. Tower Hamlets has one of the highest proportions of residents whose main language is not English; around 35% fall into this category, and of those, roughly a quarter report speaking English “not well” or “not at all” — significantly above London and England averages. This is not new information; it underpinned the Rule 6 evidence on Day 8 about the limits of consultation and the risk of formal engagement that large swathes of the Bangladeshi community literally cannot understand.

In earlier sessions, Rule 6 witnesses described consultation materials whose Bengali script was garbled and whose translations were functionally meaningless, as well as public meetings where a purported Silheti interpreter struggled to convey basic concepts of the scheme. Those testimonies were not challenged by the appellants at the time.

When Curtis put this context to Marginson, his answers echoed a pattern seen on Day 6 with the design team. He accepted the demographic reality and acknowledged the Public Sector Equality Duty in general terms, but said he could not comment on the quality of past interpreting or translations. His reference point was the appellant’s own Statement of Community Involvement — a document that lists consultation events and response mechanisms but says little about who was actually able to participate in them meaningfully.

What this leaves, once again, is a double split. On the one hand, there is a documented gap between the linguistic realities of the local population and the tools used to reach them. On the other, there is a professional insistence that because a consultation programme existed — and because it is written down — the process can be considered satisfactory. The Public Sector Equality Duty is affirmed in the abstract; its content, in relation to this specific community and this specific site, remains largely unexamined.

In the vocabulary of this series, Day 8 described consultation as part of an “architecture of decision-making” that secures legitimacy while leaving underlying logics untouched. Day 9 afternoon confirmed that architecture is still standing. The problem is not simply that some residents could not understand what was said; it is that the planning balance now being struck rests on the assumption that it does not matter.

V. “Good Growth” Without an Equality Lens

From there, Curtis turned to the language that is supposed to sit above individual schemes: “good growth,” “inclusive growth,” and the equality duty. If Day 8 morning had argued that regeneration can redistribute vulnerability, Day 9 afternoon asked whether the planner had done anything to prevent that redistribution here.

Curtis walked Marginson through the London Plan’s Good Growth objectives and their echo in the Tower Hamlets Local Plan: ensure economic success is shared, reduce spatial inequality, and make growth “sustainable and equitable so that all Londoners, and indeed residents of Tower Hamlets, can share in that economic growth.” Marginson agreed that individual planning decisions must still be tested against those aims, and that the Secretary of State must satisfy the Public Sector Equality Duty when determining this appeal.

She then re-introduced the evidence of Adam Almeida: Bangladeshi households in the UK holding roughly £30,000 of wealth on average — far below white British counterparts; poverty rates around 45%; an employment rate for Bangladeshi adults lower than any other ethnic group listed by the Department for Work and Pensions. Marginson accepted that, on the basis of that data, “this is not a section of the population that is sharing equitably” in economic prosperity.

Yet when Curtis asked what analysis he had undertaken of how the Truman proposals would impact that specific community, the answer was starkly simple: none. Marginson confirmed that he is not an expert in economic impact or equality assessment; that others had done that work; and that his own conclusion — that the Bangladeshi heritage community “will benefit” from the schemes — was not supported by any bespoke analysis of their situation.

The Equality Analysis (CDA20) supplied by the appellant does, however, contain some important admissions. On page 38, in a table analysing impacts by socioeconomic status, it notes that redevelopment of the Truman site, “when combined with other development occurring in the area, may lead to an increase in housing prices in the local area, as is typically seen with increasing development.” Curtis linked this to Almeida’s comparative evidence on how such price rises frequently spill over into commercial rents, especially in gentrifying districts.

Asked about this, Marginson’s line was consistent with the appellant’s throughout: he had seen “no evidence” that the appeal scheme would increase rents for local businesses or cause displacement outside the site boundary; what displacement risk did exist within the complex, he argued, would be mitigated by provisions allowing some traders to relocate on site.

The disjunct is hard to miss. On one side, a borough-wide pattern in which development “typically” raises prices — acknowledged in the appellant’s own Equality Analysis. On the other, a planning witness who, while accepting that Bangladeshi residents are structurally poorer and less secure in employment, conducts no specific equality analysis and sees no reason to adjust his planning judgement in light of that vulnerability. “Good growth” is affirmed as an objective, but not used as a lens.

VI. Benefits on Stilts: Jobs, Housing and 30 Hours of “Community”

The last part of Curtis’s cross brought these questions down to the level of concrete numbers: jobs, housing, community space — the familiar currency of planning gain.

On employment, Curtis directed Marginson to Tower Hamlets’ Planning Obligations SPD. Page 26 sets out an aspiration that 20% of jobs created by both construction and end-user phases should go to local residents; to support this, the SPD says developers “are required” to advertise opportunities through the Council’s job-brokerage service or local organisations. In this appeal, by contrast, the draft s106 requires only that the developer use “reasonable endeavours” to advertise a minimum of 20% of vacancies to local people. Curtis characterised this as a watering-down: a requirement to advertise becomes a requirement to try.

Marginson’s response was twofold. First, he said, “reasonable endeavours” is standard wording in his experience of Tower Hamlets’ section 106 agreements. Second, the development will fund an employment and workspace officer whose job is to help local residents access roles in the scheme, and an employment strategy to be approved by the Council could, in principle, require specific outreach to the Bangladeshi community. What he did not dispute is that there is nothing in the s106 now that expressly secures such targeting.

On housing, the figures are familiar from earlier days: 44 homes on a ten-acre site, of which six are at social rent and five are intermediate. In a borough with tens of thousands on the housing register and an acknowledged crisis of overcrowding, no one suggested that this would make more than a “tiny dent” in need. The appellant’s case is that this is an employment-led allocation where housing is a secondary, policy-compliant component; critics have argued, in this series and in evidence, that the choice to keep housing marginal is itself a political decision masquerading as inevitability.

Then there is “community”. As Curtis and earlier witnesses have explored, the scheme offers two community centres within the site, with discounted rates and 30 hours per week of secured community use. Marginson presents this as a major benefit to the local area, alongside new public connections, child-play space and access through the Brewery site without gates. Set against John Burrell’s alternative vision for Brick Lane — one of long-term, low-cost community tenancies and embedded cultural uses — it reads more like rented time than rooted presence. A booking system cannot, on its own, substitute for political and economic security.

All of these pieces come together in Marginson’s own weighting exercise at paragraph 7.90 of his proof. Under questioning from Wald, he confirmed that, with two exceptions — urban greening/biodiversity and employment skills and training — every public benefit he identifies is given “substantial weight”, the highest category on his personal scale. Skills and training, he clarified, include not only construction apprenticeships but permanent operational jobs; even so, they are one of only two items that fall below the top rank.

“Yours are remarkably uniform, aren’t they?” Wald suggested. Marginson disagreed with the implication, but not with the description. Almost every benefit is substantial; almost every harm, in the appellant’s framing, is less than substantial. As with the data-centre precedents, the effect is to compress judgement into a narrow band at the top of the scale. If everything weighs heavily, nothing truly does.

Analytical Commentary – From Capital as Client to Community as Measure

By the end of Day 9, the Inquiry had completed a small four-part cycle. Day 8 morning set out the economies of displacement: regeneration as “a redistribution of vulnerability”, not a neutral upgrade. Day 8 afternoon reframed the data centre as something more than a piece of plant – a valuation event that allows land to be reclassified and repriced. Day 9 morning then returned the focus to residents and traders: daylight, overcrowding, language and the simple plea to “give me a house” before granting more floorspace to shops and servers.

The afternoon session was where these threads met the planner’s ledger. What it revealed was not a clash over facts – almost everything was common ground – but a clash over what gets counted as need, and who gets counted as a subject of planning at all.

1. From displacement by design to calibrated “need”

From the outset of this series, Day 1 argued that the Truman scheme is “not heritage-led regeneration; it is displacement by design” – replacing social density with capital intensity on a ten-acre site at the heart of one of Britain’s poorest communities. The Great Housing Betrayal piece broadened that argument: Brick Lane is already a textbook case of a policy world that measures success by whether developers “welcome the package strongly on the day”, not whether residents can stay in the place they built.

Day 9 afternoon showed how that politics of replacement is translated into the technical language of “need”. On the office side, the Employment Land Review is clear: there is no requirement to plan for more big-box corporate floorspace; the pipeline is already more than enough. The only ambiguity lies in one paragraph about possible SME shortages – a paragraph that becomes, in the appellant’s hands, a decisive reason to treat Truman as an employment priority.

On the housing side, there is no ambiguity at all. As Day 8 and Day 9 morning both underlined, Tower Hamlets has some of the highest levels of overcrowding and housing stress in London; Bangladeshi households, in particular, face high poverty rates and low wealth. Yet that “acute” need is treated as a contextual fact rather than a driver of land-use choice. The 44 homes at Truman – six at social rent – are acknowledged, logged as policy-compliant, and then dwarfed by the weight attached to office and data-centre floorspace.

Seen against the wider series, this is not accidental. It is exactly what The Great Housing Betrayal diagnosed: a system in which housing policy is quietly recoded as financial engineering, with land use decided not by social shortage but by rent-bearing potential.

2. Heritage as commodity, heritage as edit

Earlier articles have shown how “heritage-led regeneration” operates less as a constraint than as a marketing script – heritage as commodity, not covenant. Day 2 described the way Truman’s “urban palimpsest” was reframed as a curated brand, with context treated as a source of yield. Day 6 then traced how “heritage-led” hardened into a procedural defence: what mattered was not whether heritage actually shaped design, but whether it could be cited in policy terms; consultation became proof of responsiveness even where residents’ voices were absent from the record.

Day 9 afternoon added a further layer: heritage as edit. The Quality Review Panel’s March 2024 meeting is an archetypal case. In the morning, the panel voiced unease about bulk in the conservation area, expressed concern over uniform heights along Allen Gardens, and suggested more residential overlooking of the park edge. In the afternoon, they praised the level of historical analysis and expressed support in principle. Only the latter half of that day makes it into the planning witness’s summary.

This is not a minor drafting issue; it is a mode of governance. When only the upbeat paragraphs are carried forward into formal proofs, “heritage-led” is proved by curated positivity, not by the full texture of advisory comment. The pattern matches what we have already seen with Historic England’s cautious letters and with the architects’ own descriptions of when heritage advice did – and did not – exist in written form.

In that sense, Day 9 afternoon confirms what the series has argued all along: the question at Truman is not whether there is heritage expertise in the room. It is which parts of that expertise are allowed to shape the story.

3. Data centres as valuation devices, not neutral infrastructure

Day 8 afternoon coined the phrase that now feels unavoidable: the Truman data centre “is no longer merely a structure. It is a valuation event.” Its purpose, in that analysis, is less about electrons and more about re-rating the estate – the hinge between a former industrial yard and a digitally branded corporate campus.

Day 9 afternoon gave that argument empirical grounding. The Secretary of State’s recent data-centre decisions offer a clear benchmark: very large schemes (65,000–163,000m²; 90–147MW) providing up to 3% of London’s projected capacity growth are consistently given significant weight on need. Truman’s 3MW block, by contrast, contributes a fraction of one per cent – yet the appellant invites the Inspector and Secretary of State to give it very substantial weight, the top of their own scale.

To sustain that leap, the appellant falls back on a language we have heard repeatedly in this Inquiry: Truman as a “micro-market of its own”, edge-of-City, uniquely positioned for creative industries and finance. Yet there is no published optioneering for alternative locations, and Tower Hamlets’ own officers explicitly note the existing cluster of specialist facilities elsewhere and the lack of compelling justification for this one.

In the political-economy terms developed in The Great Housing Betrayal and earlier ConserveConnect pieces, this is exactly what financialisation looks like on the ground. Heritage frontage and “critical infrastructure” become the outward face of fictitious capital – the conversion of expected future rents into present-day claims on land. The planning balance then follows suit: an infrastructure element out of all proportion to local need is treated as the decisive benefit in a borough already over-supplied with such facilities.

4. Good growth, bad distribution

Day 8 morning ended by describing planning as a contest over legitimacy: whether consultation, equality assessments and committee votes amount to real accountability or just the appearance of it. Day 9 afternoon took that contest one step further, into the language of “good growth” and the Public Sector Equality Duty.

On paper, London Plan objectives and the Tower Hamlets Local Plan commit decision-makers to sharing economic success, reducing inequality and treating growth as more than a tally of cranes. Evidence from Adam Almeida and others then shows that Bangladeshi residents in Tower Hamlets are structurally poorer, less secure in employment, and more exposed to rising costs than their white British counterparts.

Yet the planning witness who accepts that picture also accepts that he has done no specific equality analysis for that community; he leans instead on a generic Equality Analysis that quietly acknowledges development tends to raise prices while insisting that there is “no evidence” of likely displacement here. Jobs, community centres and public realm are claimed as benefits “for everyone”, with no differentiation between those capable of paying rising commercial or residential rents and those already at risk.

In other words, “good growth” functions here much as “heritage-led” does: an attractive label which, when tested, turns out to be largely distribution-blind. The categories of “significant” and “substantial” weight recognise a data centre’s contribution to capital flows with exquisite precision; they have almost nothing to say about how that same scheme interacts with a racialised, low-wealth community that has defended Brick Lane for decades.

5. From capital as client to community as measure

Across this series, a consistent alternative has been present in the background: regeneration as repair rather than replacement. John Burrell’s alternative vision for Brick Lane – “regeneration without erasure” – is one way of naming that possibility: repair before rebuild, community-owned workspace, integrated affordable housing, cultural continuity as a working economy, not a visitor spectacle. The Great Housing Betrayal offers another, in its call for cultural-heritage impact assessments, public stewardship of key assets, and enforceable quotas of affordable space for local residents and traders.

Measured against those benchmarks, the Day 9 afternoon evidence reads as a kind of stress test for the system itself. On every axis where the series has suggested a different metric – housing before speculative office, heritage as lived continuity, infrastructure as means rather than asset, equality as participation rather than tick-box – the planning balance presented by the appellant moves in the opposite direction.

That does not mean the Inquiry is irrelevant. On the contrary, as The Great Housing Betrayal argued, it is precisely in cases like Truman that the underlying doctrine is made visible: whether “growth” is defined as a rise in asset values or as an increase in the capacity of existing communities to live well where they are. Day 8 named capital as the effective client of the planning system. Day 9 afternoon, especially under Curtis’s questioning, posed the counterfactual: what if the measure of success were the Bangladeshi families, traders and tenants whose presence made Brick Lane significant in the first place?

The Inquiry cannot change the structure of London’s property economy on its own. But it can decide whether this ten-acre site will deepen that structure or begin to bend it. In that sense, the real question raised by Day 9 is brutally simple: when the Secretary of State eventually balances the scales at Truman, will the client be capital, as usual – or the community that has already paid the highest price for “regeneration” once.

Coda

As the room emptied on Day 9, nothing material had changed: the drawings were the same, the figures unchanged, the data centre still a 3MW block in a crowded borough. What had shifted was the frame. Through two days of evidence and cross-examination, the Truman scheme no longer looked like an inevitable expression of planning policy, but a choice about who counts in that policy at all. When the Secretary of State finally sits down with the same bundle of documents, the question will not be whether the numbers add up. It will be whether their meaning is taken from the balance sheet of capital, or from the lives of the people who made Brick Lane matter in the first place.

Editorial Note

This report is a fair and accurate account of open proceedings at the Truman Brewery Public Inquiry and is protected by qualified privilege under Schedule 1 of the Defamation Act 1996. Commentary and interpretation reflect the author’s independent analysis in accordance with NUJ and IPSO standards for accuracy, fairness and responsible journalism.