Day 8 – Afternoon Session: Planning as Alibi, Capital as Client

Prelude: The Truman Brewery Inquiry

This report forms part of our continuing coverage of the Truman Brewery Public Inquiry, convened to consider four linked appeals by Truman Estates Ltd over the proposed redevelopment of the historic brewery complex at the southern end of Brick Lane, Tower Hamlets.

The appeals concern three planning applications — for Grey Eagle Street (Block A), Ely’s Yard, and Truman East Campus — alongside listed building consent for works to the Grade II Boiler House. Though varied in form, the applications share a common logic: the conversion of a culturally significant site into a private, digitally branded estate.

At the core of the Inquiry lies Block A, a five-storey, 5,200 m² data centre rising to 29 metres. It is not simply a building — it is the financial hinge of the entire development plan. Framed as “critical digital infrastructure,” it allows the surrounding land to be reclassified, revalued, and reinvested.

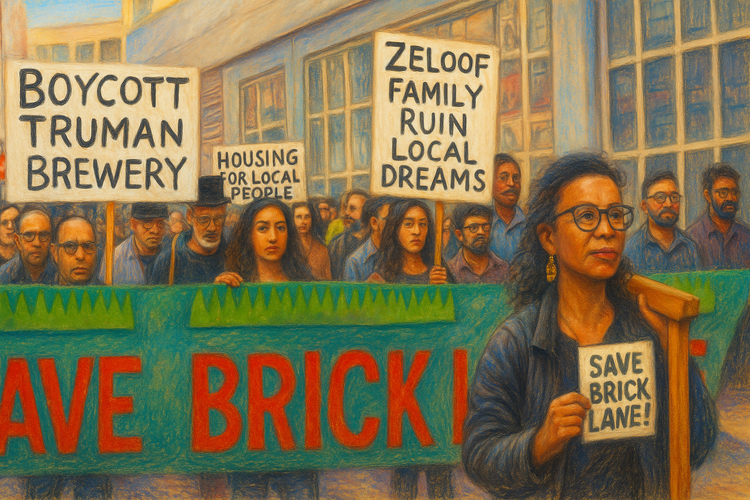

Originally appealed on grounds of non-determination, the case has since been recovered by the Secretary of State, who will now make the final ruling. Represented by Russell Harris KC, the appellants claim national necessity. The London Borough of Tower Hamlets, represented by Richard Wald KC, has resisted, citing heritage harm and planning imbalance. The Save Brick Lane Campaign, a Rule 6 Party, appears in defence of community voice and urban integrity.

As we have argued throughout this series, the question before the Inquiry is no longer how to design the city — but who the city is designed to serve: the public who inhabit it, or the capital that rents it.

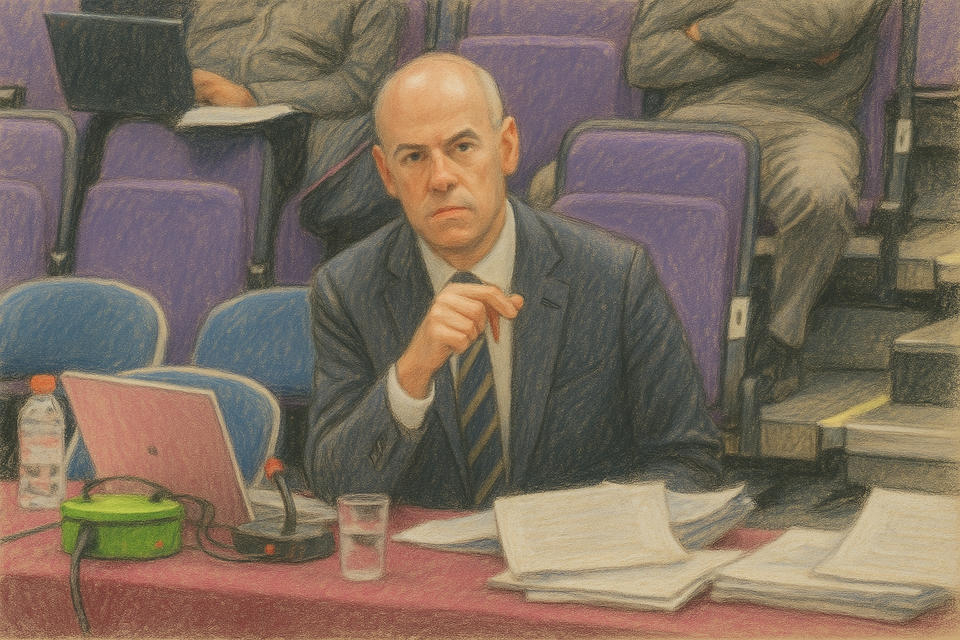

Jonathan Marginson, planning witness for the appellant, restated the development logic of the Truman Brewery scheme. But behind his language of “design intent” and “heritage integration,” a different geometry unfolded — one where planning consent itself becomes the hinge between urban place and global asset. As the Inquiry nears its end, the data centre is no longer merely a structure. It is a valuation event.

Marginson’s Frame: From Policy Compliance to Strategic Necessity

Led by Russell Harris KC, Marginson’s evidence-in-chief focused on the scheme’s compatibility with national and local planning policy, including:

- The London Plan, especially policies relating to infrastructure, mixed-use intensification, and digital economy;

- The Tower Hamlets Local Plan, where Brick Lane is classified as part of the City Fringe Opportunity Area;

- National guidance on critical digital infrastructure.

He argued that the development fulfils both strategic digital need and urban regeneration goals, describing the data centre as “essential infrastructure” that anchors the wider scheme. Where earlier iterations of the site favoured workspace, retail and housing, Marginson insisted that “the current configuration reflects evolving need.”

What remained unspoken was what that need was for — and for whom it had evolved.

The Rewriting of Place as Product

Pressed by Harris KC, Marginson described the proposal as a “balanced, context-aware” intervention. Yet this balance appeared to rest on a quiet reversal: the shift of Block A — originally peripheral — into the centre of the masterplan.

What had once been heritage-led infill had become a fortified core.

“The data centre,” Marginson said, “is now an integral and enabling element of the overall regeneration.”

That phrase — “enabling” — revealed the scheme’s true engine. As explored in The Conversion of Place and the Financialisation of London series, data centres now function not simply as digital infrastructure but as financial anchors: valuation tools used to lift the yield profile of surrounding land.

In this sense, Block A is not a node of network performance but a trigger for re-rating urban ground — a device that recalibrates what the site is worth, to whom, and on what terms.

A “Need” Without Metrics

Marginson repeatedly cited national infrastructure strategy to justify the data centre. But when asked to quantify this “need,” he offered no network stress analysis, no latency map, no evidence of digital undersupply in Tower Hamlets.

“Latency is not the primary driver here,” he acknowledged. “It’s about colocation and resilience.”

Here, as elsewhere, technological necessity gave way to financial abstraction. In Assessment of Technological and Policy Alignment – Block A, expert review had already noted that the proposed design uses pre-virtualisation architecture, suggesting limited scalability, high energy demand, and redundancy in an increasingly edge-distributed cloud environment.

What the proposal secures, then, is not network performance — but rent stability.

Planning as Procedural Legitimacy

What Marginson offered the appellants was not simply analysis but procedural credibility. His role was to show that this was not just permissible but desirable — an enactment of policy in its highest form.

And yet, the contradictions remained stark:

- The scheme offers only six affordable homes, in one of the most overcrowded boroughs in the UK.

- “Affordable workspace” is capped at 10%, and even that is loosely defined.

- No meaningful community ownership, oversight, or participatory design.

The benefits, in short, accrue not to the public, but to the project itself — through uplift, securitisation, and speculative momentum.

Analytic Commentary: From Plan to Platform

Marginson’s appearance confirmed a structural pivot in the Inquiry: the repositioning of planning as an alibi, a language of legitimacy that translates private intention into public entitlement.

This is precisely the process described in Part II – The Financialisation of London: the way capital moves not by breaking the rules, but by writing them anew — reinterpreting policy to allow the circulation of land as asset, not as place.

The data centre, in this view, is a proxy for a wider logic:

- Planning permission becomes a pricing event.

- The masterplan becomes a development pipeline.

- The city becomes a ledger of convertible claims.

In Part III – London for Sale, this is described as “metropolitan predication”: the use of planning frameworks to pre-value space — to predict, fix, and extract future income streams from land before its social meaning is even established. Within this system, public consultation becomes procedural theatre, and the Equality Impact Assessment (EqIA) operates less as a diagnostic tool than as a ritual of compliance. It signals legitimacy without enacting accountability. The real work of the scheme lies elsewhere — not in inclusion or mitigation, but in the valuation architecture beneath the plan, where consent is monetised and risk externalised.

Conclusion: The Precedent Set

As the session ended, no cross-examination occurred — Curtis and Wald reserved their questions. But the direction was clear. The appellants had made their final procedural move: to present the data centre as beyond debate, its footprint inscribed not in concrete but in precedent.

What remains now is not just for the Inspector to rule, but for the Secretary of State to decide whether this pattern holds — whether London’s future is to be built on coded justifications for capital, or on the still-possible principle that place belongs to people before portfolios.

Editorial Note

This report is a fair and accurate account of open proceedings at the Truman Brewery Public Inquiry, verified against the official transcript and Inquiry documents. Commentary and interpretation reflect the author’s independent analysis, in accordance with NUJ and IPSO standards. The report is protected by qualified privilege under Schedule 1 of the Defamation Act 1996.