Day 7 — From Infrastructure to Inertia: The Question of Need

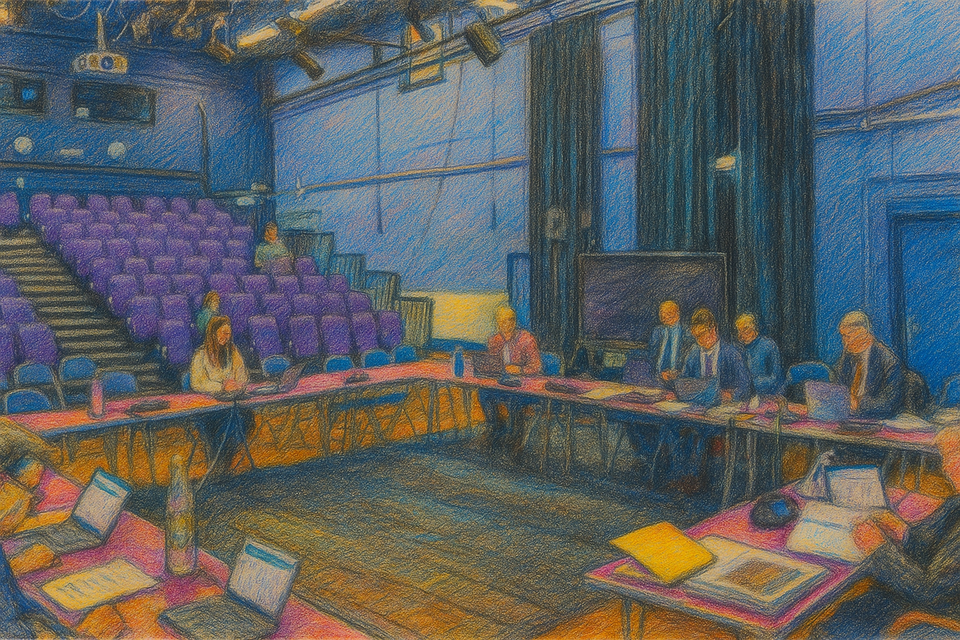

Prologue — The Hearing Room

The inquiry sits inside the Brady Arts Centre Studio Theatre: raked purple seats, a ring of tables, the lights kept low. It is an ordinary room for extraordinary questions — the fate of Brick Lane reduced to microphones and laptops arranged on pink laminate.

At the far table the witness speaks, her sentences compressed into technical certainty; around her, counsel take notes, the Inspector listens, and the public rows remain mostly empty. A theatre of necessity, performed to an absent audience.

“Those at the centre of decision are enclosed in circles of expertise; those at the periphery live with the consequences.” — C. Wright Mills

The Setting

The Truman Brewery Public Inquiry concerns four linked appeals by Truman Estates Ltd, owners of the former brewery complex at the south end of Brick Lane in Tower Hamlets. The appeals cover three planning applications — for Grey Eagle Street (Data Centre PA/24/01450), Ely’s Yard (PA/24/01439), and Truman East (PA/24/01451) — together with Listed Building Consent (PA/24/01475) for works to the Grade II Boiler House.

All four were validated on 19 August 2024 and appealed on 2 June 2025 on grounds of non-determination; they are now before an appointed Planning Inspector under the Secretary of State’s delegation. The London Borough of Tower Hamlets, as local planning authority, had earlier refused an earlier phase of the redevelopment but had not issued decisions on the 2024 applications when the appeals were lodged.

The most contested element is the Grey Eagle Street data centre, a five-storey, 5,200 m² secure facility rising to 29 metres, positioned beside an existing server building. It stands at the conceptual centre of the Inquiry — the point at which heritage, infrastructure, and finance converge.

Represented by Russell Harris KC, the appellants argue the data centre is of national necessity; Richard Wald KC leads the Council’s defence, with Mike Kiely MRTPI as principal planning witness. The Save Brick Lane Campaign appears as a Rule 6 Party, presenting the views of residents, traders, and heritage advocates.

Convened at the Brady Arts Centre, Hanbury Street, from 14 to 31 October 2025, the Inquiry asks whether this suite of developments — and the data centre in particular — represents digital progress or the financialisation of place.

This day's inquiry tests whether the appellants’ claim of digital necessity can outweigh the Borough’s democratic duty to protect heritage, housing and local economy under the National Planning Policy Framework (2024), the London Plan (2021) and the Tower Hamlets Local Plan 2031.

As Flora Curtis, counsel for the Rule 6 Party Save Brick Lane, observed on Day 1, this Inquiry has become “a contest between democracy and development — between a community’s right to place and the market’s right to possession.”

I. Scene Setting

“Is there a pressing need for data-centre capacity in this part of London?” asked Russell Harris KC, counsel for the appellants, Truman Estates Ltd.

McGinley: “Yes, there is.”

Harris KC: “Any doubt between the parties?”

McGinley: “No.”

From that moment the hearing moved at a practiced rhythm. McGinley’s answers were compact affirmations, each one closing the circle between need, qualification and authority.

Harris KC: “Are you qualified to advise the Inspector on the extent and urgency of that need?”

McGinley: “Yes.”

Harris KC: “The consequences of failing to meet it?”

McGinley: “Yes.”

Harris KC: “Is anyone else at this inquiry so qualified?”

McGinley: “No … not Mr Kiely.”

It was a performance of expertise — designed to leave no daylight between technical witness and national policy. Yet the substance that followed revealed the fragility of that authority.

II. Analytic Commentary

“Need” as Narrative

McGinley’s case rests on a tautology: because data exist, more centres must exist. She told the Inspector that London faces “a pressing need for co-location centres,” citing GPU-as-a-Service workloads and new AI tenants whose servers “have to be in proximity … and have to be in London.”

But no quantitative basis followed — no metric of megawatts, racks or latency thresholds — only anecdote. When asked if other sites might serve the same function, she answered flatly:

“No, he [Mr Kiely] has not identified any.”

The exchange was meant to discredit the Council’s witness; instead it highlighted how locational necessity was being asserted by exclusion rather than demonstrated by evidence.

AI as Alibi

McGinley framed the rise of CoreWeave and similar GPU lessors as proof that data centres must colonise the urban core. Yet her own description revealed the underlying market logic: companies lease capacity from providers who lease property.The AI era functions less as a technical imperative than as an accelerant for asset creation.

Our earlier piece, The Conversion of Place, traced the same pattern — the digital vocabulary of “high-density compute” translating directly into a property-yield model.

III. Policy Reasserted

When the session reconvened after a short break, the Inquiry’s tempo shifted.

Mike Kiely MRTPI, giving evidence for the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, took his place at the witness table — a quiet counterweight to the morning’s certainty.

Under examination by Richard Wald KC, Kiely spoke in the idiom of the development plan rather than the market. The Council’s objection, he explained, was “not to digital infrastructure as such” but to where and how it was being proposed.

“This is not a site allocated for digital infrastructure,” he said. “The appellants seek to redefine an employment zone as an infrastructure zone by assertion.”

He divided the Council’s case into three forms of harm: design and townscape, heritage, and land-use conflict — each, he said, a product of location error, a building that “imposes a single use in an area defined by mixture.”

“Need does not equate to compliance,” he told the Inspector. “Policy recognises the value of digital infrastructure, but it does not suspend the ordinary tests of good design and public realm.”

Pressed by Russell Harris KC on cross-examination, Kiely accepted that the London Plan now encourages digital infrastructure, yet he drew the line that defined the day:

“Encouraged, yes. Directed to this street, no.”

Where McGinley’s morning testimony cast the data centre as indispensable to the nation, Kiely’s afternoon evidence restored it to scale — a private, single-use facility whose benefits stop at its walls.

“There is no public access, no mixed use, and no local employment benefit beyond maintenance staff,” he observed. “The scheme produces enclosure where permeability should be preserved.”

In that phrase — enclosure where permeability should be preserved — the day’s argument crystallised. What McGinley called infrastructure, Kiely called occupation.

IV. Technical Annex — The Limits of Proximity

Centralisation vs Distribution

In Data Storage Architectures and Technologies, Jiwu Shu shows that modern infrastructure is shifting from monolithic shells to network-pooled resources (NVMe-oF, CXL). Latency-critical nodes can remain small and urban; the bulk migrates outward. Ian Gordon, in Data and the Built Environment, calls such facilities “transient capital hardware with an architectural lifespan shorter than a decade.” By those standards, the Truman cube is already legacy.

Policy Support, Not Primacy

Asked whether the 2024 NPPF or the Borough’s employment-land study explicitly examined data-centre location, McGinley acknowledged:

“No, not that I’m aware of.”

That admission collapses her claim of policy inevitability.

V. Economic Reading — Financialisation as Infrastructure

From Need to Asset

Under cross-examination by Richard Wald KC, McGinley conceded that her proof’s phrase “the Council erred in decision-making” was not a legal opinion — only “market justification … from a data-centre perspective.” It was an admission that the error lay not in law but in missed opportunity.

In Brett Christophers’ Rentier Capitalism, rentierism is “a proprietorial rather than entrepreneurial ethos … success based on what you control, not what you do.” The Truman data centre is its architectural expression: rent packaged as infrastructure.

Balance-Sheet Capitalism

Christophers describes Britain’s economy as “scaffolded by and organised around the assets that generate those rents.” Block A converts a heritage site into an income-producing instrument, its civic legitimacy derived from the rhetoric of digital sovereignty. Here, the state becomes guarantor of private rent — what he terms “institutional land-rentierism,” profit derived “not from production but from possession.”

The Urbanisation of Data — How a Small Server Farm Drives a City-Wide Economy

Recent scholarship clarifies why a data centre of apparently modest capacity can anchor an entire development plan. In Circulating Value: Convergences of Datafication, Financialization and Urbanization, Julia R. Wagner shows that digital platforms now perform “like financial intermediaries,” converting everyday activity into predictable rent-yielding flows. Datafication, she writes, is co-generative with urbanisation: it conditions the city and is conditioned by it, “instigating and accelerating the circulation of value in capitalist urban production.”

Likewise, Phillip O’Neill in The Financialisation of Urban Infrastructure demonstrates that infrastructure becomes an “investable asset class” once its physical flows — energy, bandwidth, tenancy — are monetised through capital, organisational, and regulatory structures. He observes that “urban flows are colonised by financial circuits of capital,” turning civic order itself into a means of rent extraction.

Through this lens, the Truman data centre is not peripheral but pivotal. It is the financial keystone of the wider redevelopment: a compact, high-rent machine whose mere designation as “critical digital infrastructure” inflates adjoining land values. Like a token in a financial ledger, the facility re-values the surrounding estate — offices, shops, co-working floors — as part of a digitally branded ecosystem. In planning terms, it supplies infrastructure justification; in financial terms, it supplies price discovery. The limited power load or floor area is irrelevant: what matters is the conversion of land into a capital-bearing asset under the auspices of national-infrastructure policy.

As Wagner notes, “datafication’s affordances rearrange the spatial distribution of production and redirect the circulation of money towards the corporations that control the digital conditions of daily life.” Brick Lane thus becomes not a site of necessity but a node in a rentier network — a new urban typology displacing the older city of production and trade with one of extraction and abstraction.

Risk and Return

Infrastructure rentiers, Christophers reminds us, depend on public guarantees while privatising returns. So too here: the community bears energy and heritage costs; investors harvest yield from the planning permission itself. The data centre operates as the bridgehead for that yield — a modest structure securing the transformation of the whole estate into financialised urban infrastructure.

This is not the democratisation of data but its securitisation.

VI. Conclusion — The Rentier Mask of Progress

Day 7 made clear that the debate over the Truman Brewery is not about latency or AI at all. It is about how cities are governed once ownership becomes the measure of progress. The language of “digital need” has been used to convert civic vocabulary — infrastructure, innovation, resilience — into the grammar of finance. McGinley’s testimony invited the Inspector to treat speculation as infrastructure; Kiely’s evidence insisted that policy remain a public instrument.

What divides them is not style or scale but sovereignty — over land, over language, and over the future shape of London itself.

The question before the Inquiry is therefore not how to design the city, but who the city is now designed to serve: the public that inhabits it, or the capital that rents it.

Until that question is answered with evidence rather than assertion, the only urgent work is scrutiny itself — the defence of planning as a civic act, and of democracy as the last infrastructure still held in common.

Epilogue — From Fibre to Finance: How Rentier Capitalism Builds the City

The Truman Brewery inquiry has shown, in microcosm, how the language of infrastructure conceals a new mode of property development. The proposed data centre on Grey Eagle Street is small, almost incidental in scale; yet it functions as the financial hinge of the entire redevelopment — the device through which land value is recalibrated and the surrounding estate reclassified as “digital infrastructure.” Its servers and switchgear are secondary. What matters is the status they confer: a veneer of national importance attached to a private asset.

Infrastructure as Portfolio.

Where the industrial city built power stations, the financialised city builds rent machines. The data centre is no longer a public utility but a portfolio component, designed to yield steady, securitised returns for owners and investors. It exemplifies what Brett Christophers calls “balance-sheet capitalism” — profit by possession, not production.

Policy Gap.

Neither the National Planning Policy Framework nor the London Plan quantifies “digital need” or explains where such facilities should go. In that vacuum, need becomes rhetoric — a pliable term that overrides design, heritage, and social use. The result is an urban logic in which the promise of technological progress justifies the erosion of civic space.

Public Risk, Private Return.

As Phillip O’Neill observes, financialised infrastructure converts urban flows into investable income streams. Public guarantees — planning consents, energy allocations, regulatory exceptions — underwrite private yield. The community carries the costs in energy draw, lost permeability, and the displacement of local economies, while the gains circulate upward as asset value.

Lesson.

The Truman case exposes how rentier capitalism now arrives bearing an Ethernet cable. It turns connectivity into collateral, presence into profit, and place into an accounting entry. The data centre’s glow on Grey Eagle Street is not the light of innovation but the shimmer of a new kind of rent — fibre-optic, frictionless, and indifferent to the fabric it inhabits.

Editorial Note

This report is a fair and accurate account of open proceedings at the Truman Brewery Public Inquiry and is protected by qualified privilege under Schedule 1 of the Defamation Act 1996. Commentary and interpretation reflect the author’s independent analysis in accordance with NUJ and IPSO standards for accuracy, fairness, and responsible journalism.