Day 7 — Afternoon Session: The Public Re-Enters the Frame

Prologue — The Room and Its Voices

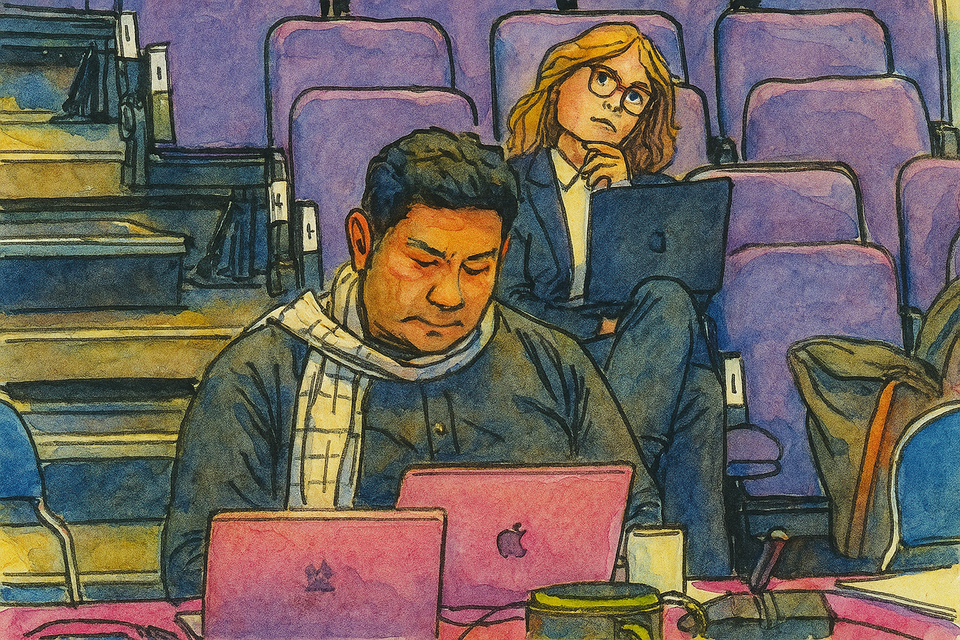

The Brady Arts Centre on Hanbury Street is an unadorned theatre repurposed for procedure: black curtains, tiered violet seats, and a ring of pink-topped tables forming a civic amphitheatre. At the centre sits the Planning Inspector, quiet behind a narrow desk. To his left, the appellants’ team for Truman Estates Ltd, led by Russell Harris KC, scroll through laptops and evidence bundles. Across from them, the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, represented by Richard Wald KC, confers with officers and witnesses. Further along the curved table, the Rule 6 Party — Save Brick Lane — occupies its place: campaigners, residents, and independent experts linking the procedural to the lived.

The hall itself tells the story the Inquiry is examining: a civic space adapted to private technology, wired with microphones and cables yet grounded in public speech. From these seats the afternoon of Day 7 unfolded — the moment when the arguments of policy gave way to the language of democracy.

The second half of Day 7 at the Truman Brewery Inquiry turned a legal hearing into a civic mirror. What began as the cross-examination of planning law became an examination of democracy itself. Through the voices of Mike Kiely, Dr Tanzil Shafique, and Saif Osmani, the Inquiry exposed the deeper question behind Brick Lane’s redevelopment: whether renewal can still be a public act in a city built on private entitlement.

The Cross-Examination of Policy

The session opened with Mike Kiely MRTPI still facing Russell Harris KC for the appellants. Their exchange, outwardly procedural, revealed a philosophical divide about the meaning of policy.

Harris KC: “Would you agree that the development plan is the first and final authority in decision-making?”

Kiely: “It is the starting point, not the terminus. Policy provides guidance, not automation.”

Harris pressed: if the London Plan encourages digital infrastructure, should that not settle the question?

Kiely: “Encouraged, yes. Directed to this street, no.”

That simple line condensed the conflict between plan hierarchy and local legitimacy. The afternoon’s exchange revealed that legitimacy itself had become the terrain of dispute. On one side stood the structured authority of plan-making — the framework through which residents and councillors negotiate change. On the other stood a new, speculative voice claiming that its “digital infrastructure” carries an inherent right to re-price the land beneath it. In Tower Hamlets, legitimacy belongs not to presumption but to participation; it lies with the community whose consent defines the plan.

Rejection as Defence

Kiely reminded the hall that the Council’s earlier refusal of the Truman Brewery scheme was not obstructionist but protective.

“The Council’s rejection was a defence of dialogue,” he said, “a refusal to lock regeneration to a model that violates the principle of participation itself.”

Kiely described the Council’s refusal not as obstruction but as judgment — an application of policy through local reasoning. He argued that the proposal’s claims of “renewal” were rhetorical rather than evidential, and that planning remained, in his words, “a matter of guidance, not automation.” His position echoed C. Wright Mills’s warning that bureaucracy, left unchecked, turns reason into routine — that governance must remain “a dialogue between power and those who live with its consequences.”

The Democratic Frame Recentred

After the recess the Inquiry widened. Dr Tanzil Shafique, urbanist and academic, approached the microphone and quietly rewrote the terms of evidence.

Shafique: “The city speaks policy English. The residents speak experience. Between them is a translation gap wide enough to build a data centre in.”

Laughter flickered through the hall; then silence. His analysis of Tower Hamlets’ consultation materials revealed how translation failures reproduce power. The Bengali versions, he noted, were “in Bangla but not the colloquial Bangla people use — technically translated, but unreadable to the women it was meant to reach.” Democracy, he argued, is not merely the right to respond but the right to understand.

Shafique: “Culture is so intangible … you can’t reduce it to a checklist.”

If Kiely restored the authority of democratic process, Shafique restored its language — showing that participation without comprehension is participation denied.

Heritage as Continuity, Not Commodity

Next came Saif Osmani, artist and community advocate. He spoke without counsel, replacing the lexicon of policy with the lexicon of memory.

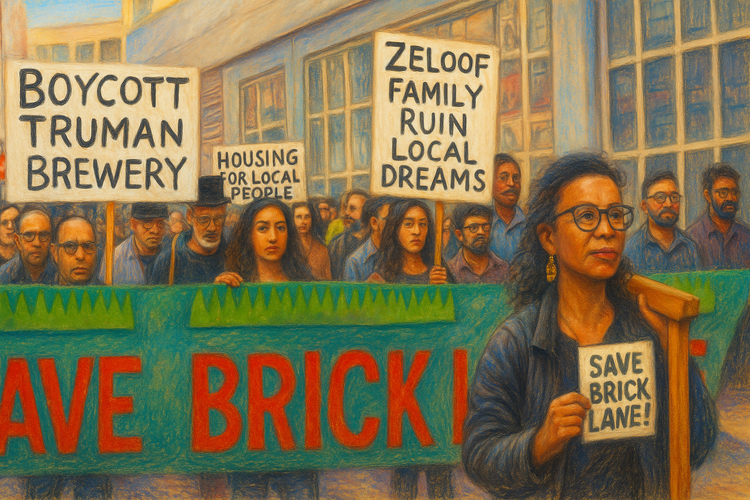

Osmani: “Everything we love about Brick Lane is becoming commercialised.”

He described the street as “a continuum of working-class culture and migration,” not an aesthetic exhibit but a lived archive.

Osmani: “When heritage is treated as façade, people are treated as shadows.”

He recalled public consultations that felt pre-decided:

Osmani: “It was an information session saying: this is what you’re going to get — like it or lump it.”

And his closing remark cut to the heart of the Inquiry:

Osmani: “The Bangladeshi community has been completely ignored — wilfully ignored. The land is worth more than the people.”

Through Osmani, ownership returned in its double sense — of property and of narrative. His evidence re-established heritage as continuity under pressure, not capital under protection.

The Turning Point

By mid-afternoon, the Inquiry’s purpose had widened beyond the Truman estate. Public testimony itself became evidence: proof that planning, properly understood, is a civic conversation. If the appellants treated participation as delay, the Council and the Rule 6 Party treated it as the condition of renewal. Their defence of the earlier refusals was not a bureaucratic reflex but a constitutional act — an insistence that the right to develop does not eclipse the right to deliberate.

To reject the scheme was not to reject change; it was to insist that change must speak the language of those it transforms.

Analytic Reflection — Renewal and Extraction

Beneath the procedural surface lay the architecture described by Phillip O’Neill and Julia R. Wagner: the fusion of digital infrastructure and finance into a single system of extraction. In their analyses, infrastructure becomes an asset-form — a conduit through which capital moves faster than consent, translating public function into private income. Day 7 made that dynamic visible.

The data centre functions as its mechanism — a compact, technically modest structure capable of re-pricing an entire district. By designating the building as infrastructure, the appellants attach to it the aura of necessity; by embedding it within the Truman estate, they multiply its financial yield. The result is an inversion: the smallest element of the scheme justifies the largest expansion of value. The public purpose of infrastructure is thus displaced by its portfolio function.

Kiely’s testimony re-situated that mechanism within governance, reminding the Inquiry that the plan remains a civic covenant, not a financial instrument. Shafique’s analysis exposed the linguistic circuitry that sustains the illusion of participation — consultation without comprehension as the cultural form of extraction. Osmani’s account returned the process to ground level, translating its cost into human terms: the slow eviction of memory by speculative form.

Together, their evidence traced a single logic unfolding at different scales — from policy text to street corner. It is the logic that O’Neill calls “the colonisation of urban flows by financial circuits of capital” and that Wagner recognises as “datafication’s co-generation of urbanisation and value circulation.” Brick Lane, in this light, is not an exception but a case study in a wider transformation: how financialised renewal feeds on the very communities it claims to revitalise.

The Inquiry, at its best, became an act of resistance to that drift. By making the mechanics of valuation audible, it restored moral proportion to technical language. The dialectic that emerged — renewal versus extraction, participation versus possession — defines not only this hearing but the condition of the contemporary city. Or, as Brett Christophers would phrase it, the shift from enterprise to entitlement: from doing to owning.

Conclusion — Democracy as a Commons

The afternoon of Day 7 was more than evidence; it was instruction. It reminded the room that democracy is itself a commons — sustained through participation, renewed through dialogue, and eroded when enclosed by private power. Where the data centre promises speed and certainty, democratic planning insists on time, understanding, and consent.

The development plans before the Inspector may yet be revised, refused — or approved outright by the Secretary of State — but the principle asserted on this day will persist:

Renewal without participation is not progress, and efficiency without understanding is not governance.

Day 7 closed not with resolution but with recognition — that the Inquiry’s most urgent construction project is the repair of the civic commons itself.

Yet that very achievement now meets its severest test. Because the case has been called in by the Secretary of State, the Inspector’s conclusions will serve only as recommendation; the final decision may rest with ministerial discretion and could be fast-tracked for approval under the government’s digital-infrastructure agenda. Should that occur, the careful weeks of testimony heard at the Brady Arts Centre — voices of planners, residents, and campaigners alike — would be compressed into a single executive act. It is a prospect that sharpens, rather than dulls, the argument of this day: that democracy, like any commons, survives only through constant tending — and dies when treated as a resource to be mined.

Editorial Note

This account has been prepared from contemporaneous notes taken in attendance at the hearing and verified against the official video recording of the session released by Tower Hamlets Council. All quoted exchanges have been cross-checked for accuracy and context to ensure fidelity to the proceedings. Some quotations have been lightly abridged or paraphrased for clarity, but all remain faithful to the substance and tone of the original testimony.

This report is a fair and accurate account of open proceedings at the Truman Brewery Public Inquiry and is protected by qualified privilege under Schedule 1 of the Defamation Act 1996. Commentary and interpretation reflect the author’s independent analysis in accordance with NUJ and IPSO standards for accuracy, fairness, and responsible journalism.