Day 5 (Afternoon) – Third-Party Submissions - The Wall Still Stands

A Street Written in Layers

For more than three centuries, Brick Lane has been a palimpsest of refuge and reinvention. The Huguenot silk-weavers who arrived in the seventeenth century built the first brick terraces on what was then a muddy path; Irish labourers followed during the famine; then Jewish refugees, whose synagogues and tailoring shops once filled the side streets of Spitalfields. When the Bengali migrants came after the 1971 war of independence, they inherited not only the workshops but also the struggles of the East End: overcrowded housing, casual racism, and the constant need to defend a place of their own.

Rachel Lichtenstein’s On Brick Lane recounts this continuity — how the old Truman Brewery’s yeast-filled air mixed with the smell of curry and wet cobbles, and how the Jamme Masjid mosque occupies a building that was successively a Huguenot chapel and a synagogue. Photographer Raju Vaidyanathan captured the same street in the 1980s, still becoming “Banglatown,” when washing lines crossed Myrdle Street and children waited outside the Whitechapel Gallery “with that uniquely youthful combination of boredom and anticipation.” In those same years, anti-racist campaigners fought off the National Front on the pavements where Altab Ali had been murdered in 1978 — a history that recent coverage reminds us “has cycled back around” amid renewed far-right rhetoric.

Through all of this, the Truman Brewery has loomed as the industrial heart of the street: six acres of malt lofts and copper vats, later studios and vintage stalls, and now the site of one of the most contested redevelopments in East London. The proposed transformation of the Brewery into an office-led complex was described in The Observer in 2021 by Jonathan Moberly, then Chair of the East End Preservation Society, as “a corporate intervention into the heart of a fiercely independent neighbourhood with a very fragile ecosystem.”

Four years later, Moberly would appear before this very Inquiry — now as Vice-Chair of the Boundary Estate Tenants and Residents Association, Chair of the Weavers Ward Safer Neighbourhood Panel, member of the Shoreditch Town Centre Police Team, and a founding member of the Save Brick Lane Campaign — closing the day’s proceedings with a precise and impassioned warning about the cumulative impact of night-time licensing and the erosion of residential life.

The Hearing

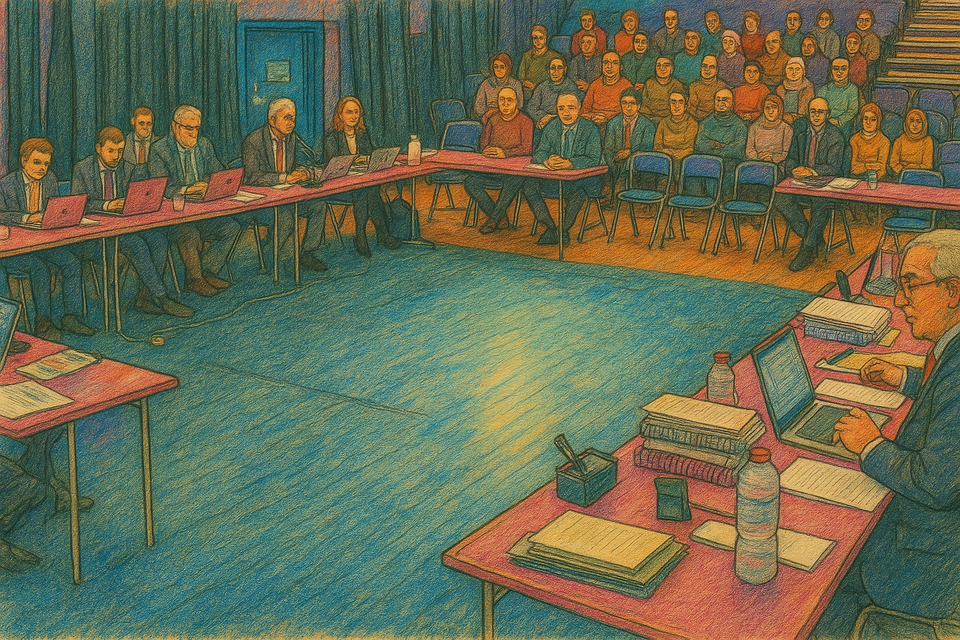

The argument over what Brick Lane will become has moved from the pavements to a stage. Inside the Brady Arts Centre on Hanbury Street — a community theatre with purple-upholstered seats and black-curtained walls — the wooden floor has been cleared for rows of trestle tables and laptops. Cables run like veins across the stage. The air hums with quiet concentration: planners on one side, campaigners on the other, and an Inspector presiding from the centre beneath the theatre lights.

Each morning of the Inquiry had begun the same way — the shuffle of paper, the low feedback of a microphone, the careful settling of chairs. But today was different. Today was the day when the public would speak.

For more than a week, the Inquiry had heard from consultants, architects, and expert witnesses. Now the purple seats behind the tables filled early: residents, teachers, traders, elders — those whose lives would be shaped by the decision. Some carried written statements folded neatly into envelopes; others had nothing but what they remembered.

By mid-afternoon, sunlight slanted through the high windows, catching on the edges of thick evidence bundles. Laptops dimmed, pens were put down. The room, for once, belonged not to procedure but to people. This was their moment — to speak into the record, to place memory beside data, to remind the Inquiry that the future of Brick Lane is not an abstraction but a lived inheritance.

Outside, the Truman Brewery remained still. Its brick façades were turning the colour of the early evening light, its courtyards empty, awaiting the ruling that would decide whether it becomes another extension of the City — or remains, in some form, part of the East End’s long story of belonging.

Akiku Roman – The Opening Voice

When the time came for the public to speak, the Inspector looked up from his notes and said quietly that there would be no particular order — anyone who wished could begin. For a moment, the room was silent: a long, waiting pause beneath the rig of theatre lights.

Then, from the second row, Akiku Roman rose.

He walked to the table, unfolded his statement, waited for the microphone to be replaced, and nodded to the Inspector. The stillness deepened as he began — his voice clear, deliberate, carrying the weight of both experience and restraint.

“Good morning. My name is Akiku Roman, and I’m here as a resident, a worker, and a father. I’ve lived in this borough for most of my life, and I’m here because I want my children to have the same right to live here too.”

With those words, the afternoon of public submissions began in earnest — not with policy or precedent, but with a voice from the community that Brick Lane built. The hall, briefly, felt less like a courtroom than a gathering — a neighbourhood speaking through one of its own.

Akiku Roman, a softly spoken man, introduced himself as having lived in the East End for sixty-two years. “Thank you, sir, for giving me the opportunity to talk here,” he began. “At least somebody is trying to listen to us. In the past we’ve been asking for lots of things, but we’ve never been answered by anybody.”

He described the area as “one community,” and said that when “any development or anything goes on, we should know first — this is our area, this is where we live.” He told the Inquiry he had spent the past week attending the hearings and had seen no sign that local residents had been consulted by the Truman Brewery or “any organisation in here.”

“So therefore,” he said, “I’d like to thank the Inspector again. He can see how many people are coming in, how many local people are concerned — because this is where they live, this is where their home is. Somebody comes and says, ‘build the buildings,’ and we have never been consulted. This is not right.”

He finished by saying residents “should be represented by their council,” thanked the Inspector once more, and sat down. There was a brief pause, then a ripple of quiet applause — not for rhetoric but for recognition. It was the first moment in five days that the Inquiry belonged to the residents rather than the experts.

Abdus Shukur – Housing Before Profit

After Akiku Roman, Abdus Shukur rose — his voice steady, seasoned by decades of neighbourhood meetings. “Thank you,” he began. “My name is Abdu Shakur. I’ve been a community worker here since the early 60s and have worked in this community with all different groups, mainly looking at local issues.”

He reminded the Inquiry that this was “the largest part of the Bengali community in the UK,” and that Brick Lane’s character had been shaped by its small traders. “What we’d like to see,” he said, “is small business units for local businesses along the frontage of Brick Lane, keeping the Brick Lane Banglatown identity rather than dissipating it by putting up large-scale shops that very few local people can use.”

Then he turned to housing. “It’s the single largest plot left in the area of land,” he said. “Some local social housing needs to be put up — yes, to ensure — that local people are housed. Tower Hamlets has more than twenty thousand people waiting on that list and it’s getting bigger, not smaller. We need to make sure people are housed rather than living in homeless units, costing the local authorities substantial sums.”

He ended simply: “That’s all I would like to say. Thank you very much for listening.” No embellishment, no rhetoric — just the practical arithmetic of fairness from a man who had spent sixty years doing the maths of community need.

Abdul Mukith Chunu – Land for the People

The next speaker, Abdul Mukith Chunu, stepped forward with the calm assurance of a man who has spent decades in community work. “My name is Abdul Mukit Chunu,” he began. “I’ve been living in and around Spitalfields and Banglatown from the late sixties.”

He explained that he had taken part in “all the campaigns about the problems we had — especially the ethnic-minority community facing issues of equal opportunity, housing, health and employment.” He mentioned his involvement in the voluntary sector — Shepherds, Spitalfields Planning and Rights of Housing Associations — organisations that had long tried to fill the gaps left by formal provision.

“But nevertheless,” he continued, “the problem we have here — we have about twenty-eight thousand people on the waiting list in Tower Hamlets Council. Always we are concerned about people’s social housing.” His concern, he said, was “mostly due to the problem of housing. We have a demand for social housing in the area.”

Then he turned to Brick Lane’s small-business economy. “Particularly, sir, if you look at the business sector in Brick Lane,” he said, “after the generations of the Huguenots, the Irish, the Jewish — then the fourth community, the Bangladeshi — we developed the businesses here. But they are now in decline because of the high rents and because we no longer have property ownership.”

He gestured toward the Brewery buildings. “Because of the situation at this moment, the Truman’s development is the only land we have left in the area. From that development, the planning, we — as a community — are demanding to have social housing, which is very important, as well as space for small businesses.” He recalled forming the Spitalfields Small Business Association in the early seventies: “but it’s not helping that much now because of the rents and the economic instability in the area.”

He ended by addressing the Inspector directly:

“Therefore we are asking that we must have some opportunity for small businesses in the area for the local community, as well as social housing for the local community too. Thank you for listening. Thank you very much.”

It was a short speech, almost conversational, but it drew the line that would run through the rest of the day: the demand that the Brewery — the last large piece of land in Spitalfields — be used to house and sustain the community that had built its prosperity.

Md Rafique Ullah – Voice of Experience

The fourth speaker, Md Rafique Ullah, approached the lectern slowly, a tall man with an easy smile that faded into weariness as he began to speak. “Thank you, good afternoon everybody,” he said. “Thank you for the lunch — I don’t know who I should thank because I didn’t pay for it.” Then, without humour, he added:

“After fifty-four years I see that someone is asking me, ‘what do you want to see?’ For fifty-four years, every day, we have been begging — to the authorities, to the enforcement authorities — ‘please help us, please bless us, all this.’ But I’m sorry, I don’t mean to offend anyone of you. I’m sure none of you live in Tower Hamlets. That’s guaranteed. So you don’t have any experience of living in Tower Hamlets.”

He described overcrowded housing, the exhaustion of families packed into one or two rooms, and the indignities of everyday racism: a pregnant Bengali woman pushed at a school gate; a bus journey where strangers demanded his seat because they could. “Unless you live here,” he said, “you do not understand. Unless you live here, you will not understand the racial harassment and the racial problems... And I don't ever want you to experience it.”

He told the Inquiry he had been called an anti-racist campaigner: “It doesn’t mean I hate all of you. I hate you when you are doing something wrong — and I will always.” Then he explained why he had come: to show how overcrowding, deprivation, and neglect were linked. “Living in drug-affected areas, is not very pleasant to live. And why these areas are drug-affected, the reason, people are living in very overcrowded conditions. Not enough housing, currently Tower Hamlets has 28,000 people on a waiting list.” he said. “Not enough space, spending their time on the staircase of a building or on the street, that doesn't help, automatically they are pushed to that situation.”

Finally, his voice softened. “Today, I am retired. I’m a pensioner. In the evenings I always wonder where do I go. Where can I go and socialise? No friends, nobody. I am feel lonely.” Looking towards the Inspector, he made a single request:

“In this new development, what are you doing? First, we need more social housing — and, above all, we need a community café where we can sit down, socialise with each other in the evening. It will be helpful for our health and not only me, those of you and others who will be reaching to Pension age, you can come and join us too.. So, finally, don't think of business, business, business, think of people living”

He thanked the Inquiry and stepped back. The chamber was silent for a moment before quiet murmurs of agreement spread through the gallery — the sound of recognition from those who had lived the same story.

Jalal Rajonuddin – The Veteran Reformer

The next speaker, Jalal Rajonuddin, introduced himself as representing the East London Community Alliance. “I am speaking against the Truman Estate’s appeal,” he began, “based on my personal story and my enduring connection to Brick Lane, Spitalfields, and the Banglatown ward for the last fifty years.” He explained that he had first-hand experience of the area’s “socio-political, cultural and economic dynamics” — and that his evidence came not from reports but from life.

He recalled arriving in the mid-1970s, homeless, “sheltered by a white working-class family,” and finding work in catering, retail, and the rag trade. “I was a youth activist organising and fighting against the far-right National Front,” he said, “and we defeated them through the resistance movement known as the Battle of Brick Lane in 1978.”

Later, Rajonuddin worked in the public sector — first at the Brady Arts Centre, then with the Bethnal Green City Challenge Company, based within the Truman Brewery and funded by central government. He went on to become an elected councillor, Regeneration Committee Chairperson, and Deputy Leader of Tower Hamlets, where he helped steer the early regeneration of the area. “I played an instrumental role,” he told the Inquiry, “in implementing Banglatown, Altab Ali Park, Soheed Minar, the Boishakhi Mela and the Curry Festival, attracting public-sector funding through City Challenge and resources from central government, Europe, and the City of London.” He said these projects had been rooted in community empowerment and the protection of cultural assets — principles he saw as under threat from the current development.

“The housing crisis, poverty, and lack of economic opportunities that I witnessed half a century ago still affect those living on low income today,” he said. “That is why I continue to campaign for social, political and economic change.” His submission, he explained, was a direct response to “the presentations made by the Truman Brewery site’s developers to this public inquiry.”

Then his tone sharpened. “The current offer of only six social-rent flats in the J Block development,” he said, “is an insult to the local community and needs to be treated with contempt.”

All brownfield land within the Truman Brewery, he argued, should be prioritised for low-cost social housing, workspaces, and accessible community spaces to improve the health and wellbeing of local residents, “in conjunction with the Council and local housing associations.”

He urged that the proposed Data Centre Hub “should not be located on Brick Lane due to its harm and inappropriate use of the site.”

“The Truman Estate is the largest commercial landlord on Brick Lane,” he added. “There are very few shops who own their own premises — most are tenants on leases, not freeholders. These local businesses have already been suffering rent increases in recent years.”

The planned ten acres of office and retail complexes, he warned, “will drive further gentrification and be the final nail in the coffin for small, independent businesses.”

“The type of catering, retail and hospitality outlets proposed within the Brewery will be out of reach for most residents, who are on low incomes,” he said. “The commercial activity is not for us — it is targeted at transient tourists, something we already see on the north end of Brick Lane.” He paused before adding:

“This expensive, modern Truman Brewery development will lead to the further demise of the remaining shops still serving local people.”

Rajonuddin reminded the Inquiry that Spitalfields and Banglatown is “the spiritual, cultural and heritage heart of the Bengali community in the UK” and must not be “allowed to be forced out or displaced.” “Instead,” he said, “cultural, housing and economic opportunities should be created and fostered so that the local community can thrive in this part of the East End.”

He concluded with an appeal for justice and equilibrium:

“We need to stop the decades of encroachments into spaces belonging to the local communities. There is a prevailing gap between big money and local needs, and we need to wake up to that reality — to re-balance the local economy to serve the people who built it.”

Finally, he declared his full support for the Save Brick Lane and Banglatown Campaign and the community plan it had developed over five years of consultation. “This is reminiscent,” he said, “of the time when I was heavily involved in developing a similar plan in 1989 under the Community Development Trust. From then till now our local community has strived to be heard. We want more low-cost social housing, genuinely affordable amenities, and community spaces to support our health and wellbeing.”

He noted that these priorities were consistent with “the commitments expressed by central government, the GLA, and the emerging Local Plan endorsed by the Mayor’s Cabinet on 15 October 2025.”

Then, turning from his notes, he held up a paperback.

“Finally, I would like to show you this book,” he said, “which has been written by a child of a homeless person who used to live down the corner from here. From Sylhet to Spitalfields by Shabna Begum. This is an account of the housing crisis that has confronted our local communities over the last fifty years — its impact on our social and economic life. It tells you about the story of homelessness, housing crisis, and of course poverty and deprivation. And I am happy to give this to you as a gift. If you are allowed to accept it — the monetary value is only sixteen pounds.”

The Inspector thanked him but explained that he could not formally accept the book, though it would be noted for the record. Rajonuddin smiled and placed it gently on the table beside him.

The gesture spoke for itself: a history of struggle and survival offered back to the machinery of planning. A brief, respectful applause followed — acknowledgment not only of the story he told, but of the book that carried it forward.

Chris Cooper – The Engineer’s Complaint

After the long view of history came a voice from the immediate present: Chris Cooper, a resident of Calvin Street, living diagonally opposite the proposed Block A data-centre. He introduced himself lightly—“the connection being with the Brewery, with the surname”—but what followed was a precise dismantling of the scheme’s logic.

“I’ve lived on Calvin Street since 2012, a few metres from the site,” he said.

“The land has been derelict for all that time and much longer. I’d welcome something positive there, but I’m not convinced that a 29-metre-tall data centre is the best use of that space, particularly in a conservation area.” He added that the argument for building more data centres simply because others already existed nearby “does not logically infer that more should follow—and in fact could instead suggest that another one should not follow.”

Cooper listed the errors he had found in the Design and Access Report, where three surrounding blocks were “wrongly labelled as workplace or retail rather than live-work or residential.” “In just one block across the street—Alpha Court—there are two dozen flats,” he said, “so it’s misleading to call the area commercial.” Community benefit, he argued, “could be much greater through housing, small businesses, or pretty much any other service that local residents would use.”

He described attending the developer’s consultation in December 2023 and submitting his contact details, only to discover nine months later that interim updates had been posted online without notice. “So,” he said, “the way the consultation was set up did not really allow for further meaningful contributions before submission of the planning application.”

Finally, he reminded the Inquiry of Interxion’s Grey Eagle Street data centre, approved in 2001–02 on strict noise conditions that had never been honoured. The Local Government Ombudsman Report 15 013 304 found those breaches to have caused years of statutory nuisance. “If you walk down Grey Eagle Street or Calvin Street,” he warned, “you can still hear the chillers at all hours. Whatever happens next must be noise-neutral to prevent a repeat.”

Councillor Asma Islam – The Policy Frame

After Chris Cooper's assured and detailed rejection of the plan, the Inquiry heard from Councillor Asma Islam, Cabinet Member for Environment and Climate Change and ward councillor for Weavers Ward, which includes Brick Lane. She spoke with the calm precision of someone who has sat through too many planning meetings where the public’s words are recorded but rarely acted upon.

“I submit this objection as a councillor for Weavers Ward — which borders the proposed development site — and as a representative of residents across Tower Hamlets,” she began. “This redevelopment is not aligned with national or local planning priorities. It threatens the cultural, economic, and social fabric of Brick Lane and Banglatown.”

She reminded the Inspector that Tower Hamlets Council’s Strategic Development Committee had refused the Truman Brewery application almost unanimously, concluding that it failed to meet borough housing policy and equality duties.

“Under the Equality Act 2010,” she said, “we have a statutory obligation to advance equality and foster good relations. This scheme fails that duty. It does not meet the needs of our residents and it exacerbates the inequalities they already face.”

She noted that office demand has declined sharply since COVID-19, leaving commercial floorspace under-used across London.

“The proposal allocates eighty-six percent of its floorspace to offices and retail,” she said. “Yet businesses have embraced hybrid working; mid-week occupancy averages around forty percent nationally. What we actually need is genuinely affordable housing — not more offices that sit empty while families share a single bedroom.”

She pointed to the developer’s token offer of six social-rent homes on a ten-acre brownfield site as “a missed opportunity to deliver hundreds of homes for those in need,” describing it as “arrogant and dismissive of public interest.”

Her statement then widened to the broader policy frame:

“Brick Lane and Banglatown are the cultural heart of Tower Hamlets — historic centres of migration, resistance, and resilience. Any development here must be rooted in collaboration, respect, and long-term benefit for the community, not speculative commercial interest.”

She warned that unchecked commercialisation would “turn Banglatown into a brand rather than a community,” undermining the borough’s efforts to support independent businesses and high-street recovery.

Her tone remained measured but resolute:

“We cannot rebuild Banglatown by pricing out its people.”

Her submission re-centred the day’s emotion within the legal and ethical framework of governance — linking housing, heritage, and equality into one coherent policy argument. She closed formally:

“I respectfully urge the Planning Inspectorate to uphold Tower Hamlets Council’s rejection and support a future for Brick Lane that is collaborative, community-led, and culturally rooted.”

Abdul Shukur Khalisadar – The Wall Still Stands

Abdul Shukur Khalisadar rose and made his way to the table and, in a voice worn smooth by four decades in E1, laid out a life measured against a single piece of brickwork.

He began at Codrington House on Brady Street in the 1980s: overcrowded, damp, “in many cases unfit for human habitation,” a block so degraded it was eventually demolished and rebuilt. In 1990 his family moved to McGlashon House on Hunton Street, where the balcony looked straight across Spital Street to the eastern wall of the Truman Brewery — tall, unbroken, and absolute. That wall, he said, was the boundary line of his childhood: council flats on one side; “acres of vacant land” on the other.

Spitalfields — later Spitalfields & Banglatown Ward — was then one of the ten most deprived areas in England and Wales. Overcrowding, poor attainment, scarce opportunity, high unemployment; “and the everyday racism that many of us endured.” As a ten-year-old, he said, the logic already seemed inescapable: bring the wall down and build homes. “That wall became a reminder not only of exclusion, but of possibility denied.”

Four decades later, the facts have changed less than the skyline. Tower Hamlets now has over 28,000 people on the housing waiting list, among the highest in London. Yet the Brewery proposals, he argued, “compete with the City rather than serve the community” — world-class workspaces pitched into one of the most overcrowded boroughs in the country. This wasn’t regeneration, he said; it was encroachment: the City pushing east while Spitalfields and Banglatown were “squeezed further.” He recalled even the early-2000s talk of parts of Commercial Street shifting from E1 to EC1 — “a symbol of the City expanding, claiming ground once firmly ours.”

From there he widened the lens — Huguenot refugees under Louis XIV; Jewish families who followed; the Bangladeshi community taking up the same mantle of craft, thrift and survival. The economy here, he said, never came from speculative finance but from kitchens, workshops and street trade — “a residential heart that worked to sustain home.” The developers’ branding of a “world-class commercial district” was, to him, a category error.

He then addressed tone as much as substance: community objections had been dismissed as “political.” They were nothing of the sort, he said — “deeper, more profound, and more respectable than politics,” rooted in lived experience and confirmed by policy evidence of housing need. Reducing hardship to “a matter of political convenience” revealed the flaw at the core of the scheme.

What followed was not anger but solidarity. In and out of the hearing room all day, he said, came Muslim mothers in hijabs, Jewish neighbours, white working-class families — “every background, every faith,” united by a single fact: this is our home. Spitalfields had always resolved its differences within the community. “What unites us is greater than what divides us — the desire to go on living here.”

He did not reject prosperity or change. “We are for development — but for the right kind,” the kind that preserves homes, honours history, and sustains a neighbourhood. The ask was simple: balance.

Then he returned to the wall. He had grown up behind it, he said, “dreaming of the day it would come down to make way for homes.” Forty years later, the wall still stands — and this proposal would, in many ways, build it higher. The question wasn’t whether to develop, but what kind and for whom. Offices that extend the City would “mark the beginning of the end” for a neighbourhood that has already given more than its share; homes and community facilities would honour the arc from Huguenot weavers to Jewish tailors to Bangladeshi garment workers.

He closed without theatrics, only an image: a Dickensian parable — “Please, sir, may I have some more?” — offered “not in despair,” but with the optimism of the ten-year-old who once stared at that wall and imagined something better. “I make this plea,” he said, “on behalf of the 28,000 families still dreaming of homes.” The moral choice, he suggested, sat plainly before the Inquiry: whether the people who built Brick Lane could go on living in the place they made.

He thanked the panel and sat down. For a moment the room held onto the picture he had drawn: a neighbourhood, a wall, and the future on the other side of it.

Dr Mohammed Ahmedullah – The Historian’s Warning

The next speaker, Dr Mohammed Ahmedullah, introduced himself as one of the founders of Brick Lane Circle, a forum for historical and cultural debate that, as he put it, “emerged in the 1990s through discussions in cafés in and around Brick Lane.” Since 2006, he explained, the group had been formally established and had organised “hundreds of seminars and discussions” on history and heritage.

“I want to say something about heritage and history,” he began, “before I go on to the main thing that I want to talk about today.”

Ahmedullah traced the relationship between Brick Lane and Bengal back more than four centuries. “If you look near Liverpool Street, Petticoat Lane, going all the way to Leadenhall Street,” he said, “you had many East India Company warehouses. They stored goods from Bengal — textiles, tea, opium, and jute. It was from here, from Leadenhall Street, that the East India Company captured Bengal and ruled India through Calcutta until 1858.”

He spoke of the traveller Ralph Fitch, who in 1586 recorded Bengal’s textiles as “one of the finest in the world,” and of the sailors from Sylhet and Assam who later crewed the ships bringing those goods to London. “So,” he concluded, “Brick Lane and its surroundings are special for longer historical reasons. We have rediscovered this through our research.”

Lifting a document for the Inspector to see, he pointed to the 1989 Community Development Plan, produced by the Community Development Group, with a photograph of himself inside. “In 1989 a consultation was held at St Hilda’s Centre,” he said. “I was employed on that project. Allen Sheppard, then chairman of the Truman Brewery, came to a packed meeting at the Montefiore Centre just across the road. He promised that regeneration, in conjunction with the Bishopsgate Goods Yard site, would benefit the local community. He said he didn’t want to replace the community — that when he retired he wanted to come back and see it thriving.”

Ahmedullah recalled how the Spitalfields Task Force, established under the Thatcher government’s Business in the Community initiative, had encouraged Bangladeshi residents to “develop leadership skills and take a stake in their own future.” “Although Spitalfields Ward then had seventy-five per cent Bengali population,” he said, “there was massive unemployment because industries had left the area. The Task Force helped us to regenerate through becoming involved with the mainstream.” From 1989 onward, he noted, the area had seen a series of government programmes — City Challenge, Single Regeneration Budget schemes, the EU Urban Initiative, and the New Deal for Communities — in all of which the Bangladeshi community had played a major role. “They helped regenerate the area, hoping it would serve them,” he said, “but when regeneration came, they found they were being replaced. This is how they feel.”

He remembered the late 1980s and early 1990s, when Brick Lane had been “quite derelict — a bit like a ghost town … a little scary sometimes, nobody there.”

It was, he said, the Bangladeshi businesses between the Brewery and Aldgate that had kept the street alive. “Yet as regeneration took off,” he added, “they found themselves unable to compete with the new situation — even though it was they who helped bring it about.”

Then his tone deepened. “As I said, going back to the 1630s, when East India Company officers first arrived on the shores of Bengal, and then 1757 when they took over — they extracted a lot of wealth, made us poor and impoverished. There is a debt the British state and system owes us for all that extraction.”

He described the Bangladeshi community’s rich traditions — of culture, textiles, crafts, arts, spirituality and intellectual life — and warned that if they were driven out, “this area will lose the future benefit we can bring from our heritage.”

“You see how effective Bangladeshis are becoming politically,” he added. “Let’s not squander that.”

Finally, he offered his plea:

“Let’s keep the Bangladeshis here and work with them to find a solution that works for everyone.”

He thanked the Inquiry and sat down. His testimony had spanned four centuries — from the warehouses of the East India Company to the housing lists of Tower Hamlets — turning a planning objection into a history lesson on extraction, renewal, and the unfinished debt of place.

Mohammed Bodrul Alom – The Trustee’s Appeal

As Dr Mohammed Ahmedullah concluded his sweeping account of Brick Lane’s four-century connection to Bengal, the hall was momentarily still — history folded back into the present. From the second row, a man in a whitish-grey shirt stood, gathered his papers, and approached the table. His movement was calm, deliberate, almost ceremonial — a continuation of the lineage that had just been traced.

This was Mohammed Bodrul Alom, a familiar figure in Tower Hamlets civic life: a long-time resident, a trustee of one of the borough’s oldest community charities, and a man whose quiet authority came from decades of advocacy rather than office. He took his seat, adjusted the microphone, and began softly:

“I start with a verse from the Qur’an,” he said, reciting in Arabic, ‘Begin in the name of your Lord.’ “I begin with this because I am a proud member of this diverse community — one of faith, of hope, and of belonging.”

His voice was steady, his phrasing careful — the cadence of someone used to boardrooms and public meetings alike.

“Tower Hamlets,” he continued, “has always been a place of constant arrival and departure — a proud and safe place for successive migrant communities. But now, we are running out of room for the people who call it home.”

He declared his strong objection to the Truman Brewery development, aligning himself with Tower Hamlets Council’s rejection of the scheme.

“It fails completely to address the acute housing crisis in our borough,” he said. “It is centred entirely on commercial and retail development for private gain, providing no meaningful or lasting benefit to local residents or the wider community.”

The precision of his delivery carried the weight of experience.

“We have families who have lived ten, fifteen, twenty years in overcrowded flats,” he said. “Some have waited three decades for a home that meets their needs — and yet, what we are offered here is more office space, more retail, no social value.”

He paused, letting the words settle before continuing.

“Developers can afford to employ expert consultants to tell us what our community wants, but that kind of desktop research is futile when it ignores lived experience. We have seen this pattern before — promises made, promises forgotten.”

From his notes, he cited the history of regeneration across the borough: Canary Wharf, “a financial success, yes — but not for all,” and Tobacco Dock, “a warning, a disaster that benefitted no community at all.”

“We must remember both,” he said. “Some regeneration has worked, but not as widely as promised. The people of Tower Hamlets have paid the price.”

Then came the appeal — calm, direct, almost judicial in tone.

“The Truman Brewery site covers nearly ten acres in the heart of Spitalfields. Surrounded by homes, shops, and small businesses, it offers nothing tangible to those who live here. We cannot afford to lose another decade, another opportunity, another piece of our borough to corporate development that delivers only for the few.”

His closing proposal turned from protest to prescription:

“Given the seriousness of the housing crisis, I urge the Government to exercise its powers of Compulsory Purchase, to acquire the Truman Brewery site for community use — to build homes, workspaces, and facilities shaped by the people of Tower Hamlets in genuine partnership with the Council.”

He ended as he began, with composure and faith:

“I ask the Planning Inspectorate to consider carefully the needs, priorities, and aspirations of the local community, and to support a plan that safeguards the identity of Banglatown and the rich cultural heritage of Spitalfields.”

He folded his papers neatly, thanked the panel, and returned to his seat — another voice added to the growing chorus that day asking for the simplest of things: space to live, dignity to belong, and a future that remembers where it began.

Lucy Rogers – The Boundary Keeper

Next came Lucy Rogers, who introduced herself simply: “My name’s Lucy Rogers. I lived near Spitalfields for twenty-three years, north of Bethnal Green Road.” She explained that in 1999 she had rented a studio space inside the Truman Brewery, “in a building in the main site yard,” under a 24-hour notice contract with the landlord — the Zeloof family, represented at the Inquiry. “I was always aware that things were temporary at Truman’s,” she said. “I had the sense they were just waiting to do a major redevelopment.”

Rogers placed the Brewery’s transformation in a longer history of encroachment from the City of London. “By now things have changed,” she said. “The Zeloof family are not the principal owners of Truman Estates — I’m not sure who is.” She recalled that in the 1990s, Spitalfields Market, a few hundred metres away, had been the site of a fierce struggle over redevelopment. “It represented the first step over the boundary by the City into Tower Hamlets and Spitalfields — to build a City office block on half of the market and occupy the remaining space with more expensive shops and restaurants.”

At that time, she said, the old wholesale market had become “a large open space that was used by the community — football, swimming pool, theatre, as well as a market. It was a place to meet and talk.” She described how the Spitalfields Market Under Threat campaign had commissioned a survey showing that the market was “well used and liked across all sections of the local community and performed an important role, particularly in mixing people together.” “There was strong opposition,” she said, “to the loss of this asset.”

When the new Bishop’s Square office development opened in 2006, Rogers walked into it with a man from the Spitalfields Small Business Association — “the SSBA that Mr Mukit mentioned,” she said. “He was a local man, his wife still lives here. He told me the market no longer felt like a space he would enter." She recalled that several Bangladeshi restaurants had been promised units in the new complex but “this did not happen.”

“All the existing shops and businesses around the edge were priced out. The property changed hands; it passed to a sovereign wealth fund in Oman. This is what happens — and what will presumably happen with Truman’s.”

Rogers said she was disturbed to hear the Brewery’s architect, Mr Yeoman, describe the new plan as a “campus.” “To me,” she said, “that was a concerning word. It’s the same issue as Spitalfields Market — but it brings large office blocks much further east, into a residential area.” She pointed out that “the size of the proposed office blocks is equal in footprint — and to some extent in height — to the Bishop’s Square office block at Spitalfields Market.”

The other architect, she noted, had said that the blocks overlooking Allen Gardens would “give an enclosure” to the park. “Yes,” she said dryly, “it will — it will close it off, by creating a giant shadow over the gardens.”

She reminded the Inquiry that Tower Hamlets ranks 29th of 33 London boroughs in hectares of open space per person, “well below the national average.” “So,” she said, “local people will lose another asset.”

“The idea of a campus,” she continued, “is a homogeneous zone with one owner, with things like curated art, as they suggest. As we heard from the architects, the tenants may be a headquarters building. So this will move the area far from being a local place to being effectively another extension of the City — aimed at commuters and tourists.”

Rogers concluded with a warning that the Brewery plan “is a continuation of the struggle about where the East End stops and the City starts, and whether the existing community gets any benefit.” Then, as a final note, she added:

“The writing of the Opportunity Area Planning Framework ignored all community input. The OAPF was steered by the City of London for its own benefit. All Opportunity Area Planning Frameworks across London lack proper consultation and transparency of process.”

Her testimony connected decades of redevelopment into one continuous map of displacement — the slow, westward march of the City into the East End, one “campus” at a time.

Dina Zimmerman – The Resident’s Case

After Lucy Rogers had traced the City’s slow eastward march, the Inquiry heard from Dina Zimmerman, a new resident of Calvin Street, whose bedroom window looks directly onto the proposed data-centre site on Grey Eagle Street.

“Hello,” she began. “I live on Calvin Street, right behind the proposed data centre on Grey Eagle. While I support the Save Brick Lane campaign and the community plan, I’m specifically opposed to the data-centre project.”

She explained that she and her husband had moved to Spitalfields less than a year earlier, drawn by “a vibrant community — the art, the restaurants, the people who really connect with one another.” She volunteers at Spitalfields City Farm, she said, and is part of CAGE — the Calvin Street and Grey Eagle residents’ group.

“This has probably brought us together faster than anything else could,” she added. “Opposition to something like the data centre.”

Her first point was about misrepresentation. “This is a residential area,” she said. “It was mis-categorised in the proposal. There are at least 150 flats that aren’t listed as residential — probably more. They have it marked as a highly commercial space. It is not.”

Her second was about safety and antisocial behaviour. “We’re already an antisocial-behaviour hotspot,” she said. “We spend much of our time talking to the police. I don’t walk on Grey Eagle Street at night. The new proposal won’t change that. The design is a blunt façade — no active frontage, no public access, no engagement with the community, and very few jobs.”

Then came noise. Referring to the Interxion data centre behind Grey Eagle Street, she said, “We’ve not had a positive experience before.” The developer’s site analysis, she explained, had only covered a 100-metre radius — “probably the minimum requirement; it should be 300.” Her own bedroom window, she said, is thirty metres from the boundary, yet “our block was not included in the noise assessment.” “So we went out and ran our own,” she told the Inquiry. “We hired a professional. Our baseline levels are significantly lower than the ones Truman used. Their proposal doesn’t say how they’ll keep the noise down — and given how little they’ve measured, it’s impossible to believe they can.”

Her fourth point was traffic and logistics. “Their loading bay comes out onto Calvin Street,” she said, “a six-metre-wide, one-way residential street with a choke point of less than three metres where Calvin Street and Jerome Street meet. It’s not suitable for high-volume traffic or large lorries. Running heavy machinery through there would be wholly inappropriate.”

Finally she turned to environmental impact and land use. “I’m not sure many of us can imagine a worse use of the land than a data centre,” she said plainly. “It provides very few jobs, solves none of the housing issues, and draws resources from the community while giving nothing back.”

She had done her own research:

“A data centre of this size would use fifty kilowatts of power per hour.

An office building of the same size uses three to five kilowatts per hour.

A flat uses five kilowatts per day. The grid here cannot support another data centre.”

The environmental costs, she added, were not limited to electricity. “The heat and carbon emissions will be significant. Paying credits doesn’t fix the problem. The racks of servers have a two- to five-year life cycle, which means a constant flow of electronic waste — most of which ends up in landfill, leaching into water and soil.”

Her conclusion was blunt and comprehensive:

“This is not the right kind of proposal for a residential neighbourhood.

It has unacceptable levels of noise, air pollution, sunlight impact and traffic impact. It will use unsustainable levels of energy. And there are almost no benefits to the community — most of the jobs won’t come from here. I just can’t think of a worse use of the space than a data centre.”

She thanked the Inspector and sat down. Her testimony left the technical case against the project impossible to ignore: a new resident’s voice turning data and decibels into the vocabulary of neighbourhood survival.

Nicola Cola – The Neighbour’s Challenge

After Dina Zimmerman’s detailed submission, Nicola Cola rose — hesitant at first, then gathering confidence as he spoke. “When I was coming in,” he began, “I was thinking if I was going to say something or not. I told my neighbour, Chris, ‘I don’t think I’m the most qualified person to speak.’ But then I guess I am, because, like many of the people behind me, I’ve been living on Calvin Street — the street where Block A would be built. I’ve been there about six years.”

He paused, looking toward the Inspector. “Listening to my neighbours, one word keeps coming back,” he said. “Arrogance. The fact that we’re even here discussing such a project for such an area can hardly be described in any other way.”

Calvin Street, he explained, was narrow and quiet most of the time — “unless they’re selling some drugs, which isn’t ideal.” He smiled, glancing toward Zimmerman: “Dina gave such a good speech, by the way. I wish I could do that, but I’ll try to wing it.”

Then he turned directly toward the developers seated opposite. “I guess you’re here to support this development, am I correct?” he asked. There was silence. “Yes? No? I was just asking,” he continued. “Do any of you live close to a data centre?” The room remained quiet. “Okay, fine,” he said. “I’d be happy to hear your experience, because maybe it’s different from ours. We already have precedent for this kind of construction — and it’s been very disruptive. We’re not even talking about the building being ugly, which it is. We’re talking about it being disruptive to the community. But if you don’t live close to a data centre, maybe you’d like to?”

The silence deepened. Cola shrugged. “All right, let’s make that a rhetorical question.”

Turning to the glossy display boards at the front of the hall, he pointed to the images. “At the end of the day, where I live does not look like this. These renderings — very nice, calming colour palette, very professional — but they don’t show what’s actually there. The people in these pictures aren’t us. And they’re not happy, because they live close to data centres. Well — yet another data centre.”

He looked back toward the developers’ table. “I can see that some people do this professionally,” he said evenly. “They’re probably very good at it. For a project of this scale, you’d expect the best. But, Sir,” he added, turning to the Inspector, “this is not a rendering. This is our neighbourhood.”

Then, with a small gesture toward the door, he concluded:

“Once you leave this Community Centre, I invite you to walk down Calvin Street. I’m going that way anyway. I’ll show you the site we’re talking about. I’ll show you what Calvin Street is.”

He thanked the Inquiry and stepped back. There was a flicker of laughter and a murmur of approval — the sound of a room recognising the clarity of an ordinary resident who had just reminded everyone that planning, in the end, is about where people live.

Terry McGrenera – The Caretaker’s Witness

After the neighbours of Calvin Street, the Inquiry heard from Terry McGrenera, a long-time local caretaker and resident of Spitalfields. His voice carried the rhythm of someone who deals in practicalities rather than abstractions.

“My name’s Terry McGrenera,” he began. “I’ve lived and worked around here for over thirty years, looking after housing blocks across Bethnal Green, Spitalfields and Whitechapel.”

He told the Inquiry that he was not a campaigner, “just someone who sees how people are living, day in and day out.” “I see the overcrowding, the damp, the antisocial behaviour — all the things that never seem to change,” he said. “And I ask myself, when I look at these plans: how does any of this help the people who are already here?”

He described how residents he spoke to could see the empty Brewery yards from their windows. “They ask why that land can’t be used for housing,” he said, “or for something useful — a park, a playground, a workshop for young people.”

He warned that the proposed construction works would bring “noise, dust and vibration,” and said that “for people with asthma, for children trying to do homework, that’s not something you can just shut the windows on.”

Then his tone hardened.

“We keep hearing the word regeneration,” he said, “but regeneration for who?Across the road from families living five to a flat, you’re planning a data centre that’ll run all night, burning power and giving nothing back.”

He urged the developers and councillors to “spend a week walking the estates instead of drawing them on maps.” “You’ll see what needs regenerating,” he said. “It’s not the Brewery — it’s the housing stock, the lifts that don’t work, the playgrounds that are falling apart.”

McGrenera ended simply:

“People around here don’t want favours. They just want fairness.

If development’s coming, make sure it fixes something that’s broken.”

He thanked the Inspector and stepped aside, leaving behind the clear voice of a man who knows the borough not as an idea, but as a set of doorways he has opened for decades.

Dr Fatima Rajina – The Scholar of Memory

The next speaker was Dr Fatima Rajina, senior lecturer at the Stephen Lawrence Research Centre, De Montfort University, and a founding member of Nijjor Manush, the organisation whose name means “Our Own People.”

She began by introducing herself as an academic who had been researching the East End for more than a decade, with publications on the Bangladeshi diaspora in London, Birmingham, and Luton. “I recommend,” she said, “the works of Prof Claire Alexander, Prof John Eade, Prof David Garbin, Prof Katy Gardner, Dr Shabna Begum, Dr Aminul Hoque, Dr Victoria Redclift — and many others — for anyone who wants to understand this community in context.”

Rajina described Brick Lane as “a breathing archive, capturing resilience and reinvention through different patterns of migration.” “This area,” she said, “is a cultural and historical landmark, not a blank canvas for corporate development. I wish you could see my students and how this lane brings their textbooks to life. They beam at seeing this before their eyes, and as sociology students they recognise the need for communities to have access to land and amenities that foster belonging.”

She paused, then continued with quiet force:

“These applications don’t represent progress. They represent erasure — erasure of community, erasure of identity, and crucially the erasure of a rich, textured history that belongs to all of us.”

Turning to evidence, she cited Trust for London’s analysis showing that the three most gentrified neighbourhoods in the city — Spitalfields, Aldgate and Bethnal Green South — are all in Tower Hamlets. Reading from the report, she quoted its chief executive, Manny Hothi:

“‘This research points to something many Londoners have suspected for years — the city is becoming increasingly unaffordable for low-income families. We’re witnessing families and long-standing communities being priced out on a scale we haven’t seen before.’”

She linked this to findings from the Common Wealth think tank and from the Runnymede Trust’s study Beyond Banglatown led by Prof Claire Alexander, all showing the rapid closure of small family-run businesses.

“The East End isn’t just studied in history books,” she said. “It is the history. As an academic and researcher I can attest that it forms a key part of multiple university degrees — in history, sociology, urban studies, cultural geography, architecture, and more. Students from around the world walk these streets to learn about immigration, class struggle, post-industrial Britain, and multiculturalism in modern London.”

Then she drew the line that would define her argument:

“In the grand scheme of things, the East End is a classroom — and the Truman Brewery is one of its textbooks. Turning that textbook into a corporate façade is vandalism — an intellectual vandalism. You can’t teach the lessons of Brick Lane from a glass-walled office complex that’s been scrubbed of memory. You can’t understand the story of the East End if you remove its storytellers. Facades don’t tell stories.”

She made clear that her position was not anti-development:

“This is not anti-growth. This is not nostalgia for nostalgia’s sake. This is a fight for meaningful progress — one that respects heritage and empowers communities. Change is constant, but that change ought to take the community along rather than disparaging it.”

Echoing earlier speakers, she argued that any development “must prioritise social housing — not affordable housing — alongside GP surgeries, green spaces, community facilities, and access to childcare, which we know is like taking on a second mortgage.”

Then she turned to the political roots of the housing crisis, quoting Margaret Thatcher’s 1981 interview in The Sunday Times:

“‘Economics are the method; the object is to change the heart and soul of the people.’” “That,” Rajina said, “was a desire to dismantle society itself — because she did not believe in such a thing as society or community. These applications persist with that ideology, creating further divisions.”

She closed with a final appeal:

“What we are seeing here is a community with its heart and soul in Brick Lane trying to assert its role — demanding economic methods that consider its needs rather than displace them. Brick Lane tells a story that cannot be rewritten by developers. But it can be erased — if we let it. So let’s not let

Abul Kahar Ali – The Coalition-Builder

The afternoon’s tone sharpened with Abul Kahar Ali, who introduced himself as “born and bred here in Spitalfields and Banglatown, brought up around Petticoat Lane.” He described a lifetime spent in public work — “from market stalls in my teens, to youth and community work, outreach with local drug users, and now management consultancy within the social-care sector.”

“My colleague Shukur earlier used the analogy of Oliver Twist,” he began. “The one I’d like to use is David and Goliath.” Looking across the chamber, he continued:

“From the left of this room, over the last week and a half we’ve seen very expensive suits — a well-funded, well-resourced campaign that’s been running for years, undermining the community and looking at a bottom line of profit and self-interest.”

In contrast, he said, the Save Brick Lane Campaign had “banded together — a rainbow of different people from different walks of life.”

“We’ve got the Bangladeshi community, the white middle-class community, the local white working-class community — and, to set the record straight, many local businesses as well. I own businesses here myself. Our legal team and campaigners have been charitable with their time, but it’s been very difficult for us to collect our pebbles together for this struggle against Goliath.”

Ali said the Brewery proposals were “entirely focused on large floor-space offices,” driven by commercial return alone. “Even with the proposal of four so-called affordable homes on such a vast land mass — it’s beyond a joke,” he said.

“The brief for the architects — yes, very nice designs, very nice architecture, nobody can doubt that — but the brief has been for the maximum amount of office space. Whatever needs to be done can be justified later.”

He paused to look around the room. “Brick Lane isn’t just the Bangladeshi community,” he said. “We are a mosaic — different people from different ethnicities, faiths and non-faiths. As you’ve seen this week and a half, that mosaic has come together. Yes, the Bangladeshi community has endured impoverishment and desperation for decades, but we all share this place. We want to see some bright hope for our next generations.”

Turning to the question of consultation, his tone hardened.

“What consultation?” he asked. “Certain consultants were hired — but many people were misled, and many aspects of this project misrepresented. Selected individuals were targeted and taken to orchestrated sessions. I say this strongly because I am personally aware of some of the shenanigans that happened in the background.”

He contrasted those experiences with the council-led master-plan consultation, which he said was the first time the community had truly been listened to. “Sadly, because of limited resources and legal constraints, that master plan had to be shelved,” he said. “We are aware of the new Local Plan that has been proposed and we hope that whatever decision is made here will incorporate its principles — because the outcome of this Inquiry will have ramifications for years and decades to come.”

Then he brought his argument to a close:

“We ask that the Inquiry prioritise not just planning regulations and frameworks but also the needs, wishes and the real-world impact this development will have. One of my colleagues asked earlier — does anyone on the team to my left live next to a data centre? I highly doubt it. Such dense massing will decimate the local area. Businesses are worried that it will push up their rates and rents. Our request is simple: be our pebble against Goliath, and stand with the community in this struggle.”

He thanked the Inspector and sat down. His speech left the phrase David and Goliath hanging in the air — a metaphor that had moved from story to strategy, defining how the day itself would be remembered.

Faysal Ahmed – The Restaurateur’s Son

When Faysal Ahmed took the microphone, his opening line carried both gratitude and quiet resolve. “Good afternoon, Sir, and thank you for giving us the opportunity to speak today,” he began. “My name is Faysal Ahmed, and I was born and raised in Brick Lane.”

His family’s story echoed that of many in the room. “Three families, including my own, began their lives in the UK in one small flat above 130 Brick Lane — just four doors down from the Truman Brewery,” he said. “We went on to open one of the very first Bangladeshi restaurants here, The Nazrul, in the 1970s.”

He recalled running a Sunday stall on Cheshire Street at the age of eleven, playing football in “the Gutt,” and sneaking into the derelict Brewery as a teenager “to imagine what it could one day become.” Then his tone shifted: “But today I’m here to oppose these development proposals.”

The Brewery site, he argued, “holds enormous potential” but the plans before the Inquiry “will do nothing to address the housing crisis or meet the real needs of local residents.” Instead, they would “accelerate gentrification and displacement — pushing out the very working-class families who helped make Brick Lane what it is today.”

He listed what the scheme offered: “Luxury apartments local people will never afford, thousands of square feet of empty office space, and six social homes — on a ten-acre site.” Against this, he set the Save Brick Lane community plan: “Up to 245 homes, 44 family-sized social units, public squares, and genuine community space.”

Ahmed ended with a simple contrast:

“This community — and the generations before us — built Brick Lane, not the Truman Brewery. It would be a tragedy to see its legacy destroyed by the greed of one developer.”

Mayor Lutfur Rahman – The Civic Appeal

When Mayor Lutfur Rahman addressed the Inquiry, the hall settled into silence. “Thank you for the opportunity to address the Inquiry today,” he began. “I speak not just as the elected Mayor of Tower Hamlets, but as a lifelong resident who has experienced first-hand the impact of gentrification on our communities.”

He described neighbours forced out after generations, families “living in overcrowded conditions while developments were approved that offered no social housing, no family homes, and no relief from rising rents.” His administration, he said, had made it its mission “to tackle the housing crisis by building thousands more social and affordable homes and protecting against developments which cause gentrification.” “That does not mean opposing development,” he explained, “but ensuring that development benefits the local community and meets residents’ needs — rather than taking away from what makes our borough so special.”

Brick Lane and Banglatown, he said, were “the heart of our community — the crown jewels of Tower Hamlets.” Turning the Truman Brewery into a mall, he warned, “risks making this culturally and historically significant site unrecognisable.”

Rahman referred to the Spitalfields and Banglatown Masterplan and Supplementary Planning Document, both created through community consultation, as models of “regeneration that reflects and celebrates the unique history and character of Brick Lane.” “I am a product of social housing,” he continued. “I know what it means. A decent, warm, affordable home keeps communities together, promotes inclusion and diversity, and celebrates cultural heritage.”

He then set out the borough’s housing statistics:

“Nearly 29,000 households are on the waiting list.

Over 13,000 live in overcrowded conditions.

More than 600 families require rehousing due to medical needs.

And yet this scheme — on a ten-acre site — offers just six homes for social rent.”

“This,” he said, “is simply not acceptable in a borough like ours.” He called the development “a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity” to meet local need, warning that approval “would be a scandal” when so many families live “five to a flat, in homes with mould, damp, and children who can’t breathe.”

Rahman argued that the Brewery scheme “would not only fail to deliver homes, but actively drive up prices, displacing working-class and ethnic-minority residents.” He pointed to the success of the borough’s Accelerated Housing Programme, which aims to fast-track more than 3,300 new homes, and said, “we cannot afford for a site of this scale not to address the community’s need for social housing.”

He dismissed claims of “cultural benefit” through cinemas and venues within the scheme: “We already have the Brady Arts Centre, Genesis Cinema, Rich Mix, Montefiore Centre, Toynbee Hall, the Kobi Nazrul Centre — spaces that are affordable and rooted in our community.”

Gentrification, he said, “changes the demography of an area — its class, ethnicity, and age — stripping away what made it unique.”

“It would be a travesty,” he said, “for that to happen to Brick Lane. People come from all over the world to walk its cobbled streets, to see its murals, to taste its curries and bagels — not to visit another commercial mall like those in Canary Wharf.”

He recalled the recent revival of the Brick Lane Curry Festival, which drew over 20,000 visitors, as an example of community-led renewal. “That spirit,” he said, “is under threat from gentrification, which risks pricing out the very businesses that built this place.”

The Mayor then turned to the question of democracy. “The Save Brick Lane campaign represents a diverse coalition from across the borough,” he said. “Over 7,000 residents have objected to this development, and the Strategic Development Committee voted almost unanimously to reject it.” “If such a controversial proposal were to go ahead in the face of overwhelming community opposition,” he asked, “what message does that send about who our democracy serves? What message does it send to families living in overcrowded homes — that their lives don’t matter?”

He described visiting families “living a nightmare — two parents and five children in two rooms, walls black with damp, children suffering from asthma and eczema.”

“How,” he asked, “can this development — with only six social homes — be explained to families like these?”

He reaffirmed his support for the Committee’s decision to refuse the scheme, noting that it failed to meet local housing needs and would cause “harm to the character and appearance of this historic area.” He concluded by citing the seven principles of the Spitalfields and Banglatown Masterplan Vision — from prioritising social housing and supporting local business to retaining cultural identity and green space.

“This proposal,” he said, “meets none of those principles. In fact, it undermines them all.”

Rahman’s final words distilled five hours of testimony into a single line of civic reasoning:

“The proposal to turn the Truman Brewery into a commercial mall is not just a planning issue — it is a social justice issue. It fails our community, undermines our heritage, and threatens the future of Brick Lane.”

He urged the Inquiry to “listen to the voices of residents, uphold the principles of our local plan, and reject this harmful proposal.” The hall fell quiet again — not out of ceremony, but from the weight of hearing a Mayor speak as one of his own constituents.

Dan Cruikshank – The Historian’s Warning

As dusk drew over the hall, Dan Cruikshank stood — historian, broadcaster, and trustee of the Spitalfields Trust, the organisation that half a century earlier had fought to save the same streets now under review. “Good evening,” he began. “I’ve lived in this area since the late 1970s and have enjoyed every moment. The Trust was founded fifty years ago to fight to save Spitalfields — to find beneficial uses for its historic buildings at a time when many were under grave threat.”

He spoke with the reflective warmth of someone who has lived his subject. “When I first got to know Spitalfields intimately, in the late 1960s, it fascinated me — the sense of life thriving in such challenging circumstances. It has always been a place defined by migration and diversity — from the Huguenots of the seventeenth century to the Jewish families fleeing persecution, to the Bengali community who made it their home. It has been a place of contrasts — wealth and poverty, fragility and vitality — but always with a pulse of life.”

Gesturing toward the walls of the Brady Arts Centre, where the Inquiry was being held, he noted its history: “This building, founded in 1896 and rebuilt in the 1930s, was a philanthropic project — created to educate, inspire, and motivate the children of the area’s Jewish poor. It shows what communities can achieve when they work together — not for profit, but to make life better.”

The Trust, he said, had inherited that same purpose. “In the 1970s our mission was not just to save the fabric, but to save the community. We restored derelict houses to residential use, created homes and workshops for people, and sought to sustain the mixed-use character that makes communities flourish — small buildings of varied design, places where people live and work side by side.”

Then his voice darkened. “Now, all that is under threat. The old Truman Brewery stands at the very heart of Spitalfields. What happens on this crucial site will define the future of the area — for good or for ill.” He made clear that no one opposed change itself. “New buildings can be added,” he said, “but they must reflect the area’s distinct character: small scale, mixed use, and with social housing. People need homes, not more office space.”

He spoke of the need to serve “the long-established and vibrant Bangladeshi community,” warning that without sensitivity, “Spitalfields would become a place few would want to visit, its wider economy — especially the Bangladeshi economy of Brick Lane — diminished.”

Looking directly at the Inspector, he offered a quiet but urgent plea:

“This is an historic moment for Spitalfields. If the wrong decision is made, then a place most of us love, and many of us call home, will become but a memory — another milestone in the erosion of London’s identity and character. Another community that offered great public benefit will be lost in the quest for private profit.”

He paused, the weight of years audible in his voice.

“Fifty years ago, I was part of a battle to save Spitalfields. And now, astonishingly, I find myself here again. The same values — the same threats — the same stakes.”

Then, with a faint smile of endurance, he concluded:

“So I urge the Inquiry to reject this scheme — and to promote all those things that make this place what it is.”

When he sat down, the room stayed silent for several seconds — not out of deference, but out of recognition that the struggle he described had come full circle.

Mohammed Rahman Jr – The Generational Voice

As the evening session drew on, a hush settled over the hall. From a front row seat, a young man rose — Mohammed Rahman, perhaps no more than 14 — holding a printed page in both hands. An older man, seated beside him, gave a brief nod of reassurance. Before he began, a request came from the chair:

“Can we just ask that no one films or records this, please?”

Then, steadying himself, Rahman spoke — clear, composed, and unhurried.

“Good evening, everyone,” he began. “This is the story of how I, Mohammed Rahman, came to stand before you today. It’s the story of my family — but also the story of many Bengali families who made East London their homes.”

He read with quiet confidence, each word deliberate, carrying the weight of generations.

“We didn’t all arrive here at once,” he continued. “We came gradually, generation by generation — each separated for part of our lives, but always connected by this place.”

He traced his lineage through the decades:

“My great-grandfather came from Bangladesh in the 1950s. He managed to buy a small property next to Allen Gardens — our family’s first home in London. His son, my grandfather, joined in 1965, when he was just fourteen. I never met him, butI’ve heard so many stories about him from my father — stories of struggle, pride, and hope.”

His voice was steady, the phrasing exact, as if rehearsed many times but still sincere.

“My father also spent his early years in Bangladesh before coming here with my grandmother in the early 1980s. Today my father is well known in our area. When I walk down Brick Lane with him, people stop every few minutes to greet him. He’s respected. He’s loved. Sometimes I find it a bit repetitive,” — he smiled slightly — “but I also know this is what community really means.”

Then came the turn — a pause, and a shift in tone.

“But there’s one place where that feeling disappears: the Truman Brewery. I walked there once with my father, and it felt like another world. No one spoke to him. No one even looked at us. I would like that to change.”

He looked up from the page, meeting the panel’s gaze directly.

“I would like the Brewery to open its doors — not by building offices, but by building homes, spaces, and opportunities for the people who already live here.”

And then, the quiet crescendo — the line that drew the room into stillness.

“My great-grandfather, my grandfather, and my father were all immigrants who found a home in East London. I was born here. This is my home — and my identity.”

He turned slightly toward the developer seated across the chamber.

“So I ask you, Mr. Zeloof,” he said softly, “let me shake your hand, sir, and let’s build a future here together — one that honours the past, respects the present, and truly belongs to the people of Brick Lane.”

When he finished, there was no applause — only silence, the respectful kind that comes when something larger than argument has been said. A young man had read from a sheet of paper, but it sounded like a vow spoken for generations.

Mohammed Miah – The Economist’s Case

When Mohammed Miah approached and sat to speak, the mood in the room shifted from emotion to analysis. “Good evening,” he began. “I’ve lived near Brick Lane and the affected area for close to fifty years. I want to argue against the proposed development primarily from an economic perspective.”

What followed was precise and methodical — a briefing disguised as testimony.

He started with office capacity.

“London does not require more office space,” he said plainly. “The City of London has a vacancy rate of around ten per cent; Canary Wharf about eighteen — and both are rising.” Post-Covid leases were expiring, he noted, while hybrid and home-working had permanently altered demand. “If the proposed Employment Rights Bill becomes law, work-from-home will be further embedded, especially in the public sector.” His conclusion was stark: “Existing capacity — plus what’s already in the pipeline — will meet London’s needs for the next twenty to thirty years.”

Turning to the wider economy, Miah described Britain’s growth since 2017 as “anaemic, even deceptive,” predicting a deep recession by 2026. “London’s office vacancy rate could reach twenty per cent,” he said, “Canary Wharf thirty-five. In that context, new offices at the Truman Brewery make no economic sense.”

He explained the substitution effect: companies would simply relocate from older buildings into newer ones at cheaper rents.

“There would be no net economic benefit — merely a shift of activity a few streets east from the City into Tower Hamlets.” At best, he said, the scheme was “economically neutral for London as a whole; at worst, it could depress rents and reduce measured GDP.”

Then he turned to local impact. “The Truman Brewery would effectively become an extension of the City of London,” he said. “The amenities available to City workers are already here. The spillover for residents in E1 would be minimal.”

By contrast, he explained, Canary Wharf had once succeeded because it met two unique conditions: “London needed the space, and the Wharf developed its own ecosystem.” Neither, he said, applied here.

Drawing on comparisons with Liverpool and Stratford, he argued that genuine regeneration required an anchor employer — government departments, universities, or industries that rooted jobs locally. “None of that exists in this proposal,” he said.

To illustrate, he offered a striking hypothetical:

“If Goldman Sachs moved from Shoe Lane to the Truman Brewery, the arithmetic would make E1 look like the most productive postcode in England. In reality, nothing would change. The same staff, the same work, the same lunches — just five minutes further east.”

The audience laughed softly, but the point landed: relocation without redistribution.

Miah then advanced an alternative — a social-housing-led redevelopment.

“Increasing social housing meets real need and has genuine local impact,” he said. He calculated that 300 family homes at social rent would save each household roughly £1,600 a month compared with private rents. “That additional income would be spent locally — on food, essentials, life itself,” he said. “Three hundred families lifted out of poverty; a direct, measurable boost to the neighbourhood economy.”

He warned that the Brewery’s current plan threatened Brick Lane’s existing entertainment ecosystem — the curry houses, cafés, and clubs that anchor local trade and tourism.

“If Brick Lane loses its culinary pull,” he said, “the visitors go elsewhere. Replace the restaurants with chains, and the street becomes just another City frontage.”

Addressing the wider borough, he turned to Canary Wharf. “Canary Wharf supports large sections of Tower Hamlets,” he said, “but it’s struggling: HSBC, Credit Suisse, State Street — all relocating. Vacancy could soon hit 30 per cent. We may face a commercial property ‘doom loop.’ Extending the City eastwards through the Truman Brewery would undermine Canary Wharf’s recovery and work against the borough’s own interests.”

Finally, he dismantled the argument for data centres. “Yes, they’re necessary for AI,” he said, “but most AI development happens elsewhere — Oxford, Cambridge, Boston, New York. What would sit here are servers for financial trading — activities that add little to the real economy.”

“Data centres are rooms of computers built abroad, running software written elsewhere. They should be on brownfield land at the urban edge, not in the middle of a residential district.”

He ended with two alternative pathways for regeneration — Aldgate East and Sidney Street — both examples of mixed-use schemes that deliver social housing and still remain viable.

“If those developments can meet local needs and be financially sustainable,” he said, “then so can the Truman Brewery.”

Then, after nearly fifteen minutes of steady, reasoned testimony, he closed simply:

“That’s where I will end. Thank you.”

The room was quiet again — not out of emotion this time, but because the argument had been rendered in numbers that no one could easily refute.

Dr Farhana Malik – The Psychologist’s Warning

As the evening deepened, Dr Farhana Malik stepped forward — calm, deliberate, and quietly commanding. “Good evening, guys,” she began, with an easy warmth that drew the room back from fatigue. “My name is Dr Farhana Malik. I’m a qualified clinical psychologist — and a child of Tower Hamlets. I was brought up here, just around the corner, and I work here now.”