Day 4 Morning – The Architecture of Justification

The Ritual of Record

Day Four began without spectacle. There were no slides, no diagrams—only the controlled rhythm of question and assent. Russell Harris KC, for the Appellant, led the morning as both narrator and choreographer, guiding the architects of Morris + Co. through a textual audit of their own work. Every statement was prefaced by his cue—“for the record,” “consistent with the principles of planning,” “that’s right, isn’t it?”—each one transforming uncertainty into confirmation.

This was not evidence but reiteration: the legal language of compliance performed as fact. In the absence of visual display, the Inquiry became a theatre of paperwork, its authority drawn from tone rather than proof.

From Design to Doctrine

Architect Jo Morris was first to speak, her answers framing the Appellant’s scheme as the natural extension of planning orthodoxy. Revisions requested by officers, she said, had been “fully addressed.” Harris prompted each assurance, turning critique into consensus. The exchange resembled a duet in administrative harmony—design translated into legal syntax.

The effect was cumulative: every doubt absorbed into procedure, every correction recast as improvement. By the time the architect stepped down, the act of revision itself had become the evidence of perfection.

Enter the Expert

Then came Michael Alan Dunn, heritage consultant for the Appellant and former team leader at Historic England. Nominally an independent expert, he arrived as a witness already contained within the solicitor’s script. Harris led him line by line through his Proof of Evidence: each paragraph introduced, each conclusion endorsed, the rhythm identical— “Yes, that’s correct… Indeed… No harm, enhancement overall.”

The choreography was subtle but decisive: the lawyer’s authority ventriloquised through professional expertise. It was a performance of knowledge in the passive voice, the expert led by the client. What Mills once called the intellectuals of the power elite—technicians who provide the vocabulary by which institutions justify themselves—was here enacted in real time.

The Reversal of Harm

Dunn’s written proof turned heritage language inside out. The Brick Lane and Fournier Street Conservation Area, he argued, was “characterised by poor-quality buildings and spaces resulting from post-war demolition,” and the proposed redevelopment would “enhance” its significance. Where the statutory duty demands that change cause no harm, Dunn’s reasoning transformed harm itself into opportunity.

To demolish, he implied, was to heal; to rebuild, to preserve. Each fragment of neglect became the moral pretext for construction. The rhetoric of enhancement operated like an economic law of exchange: loss redeemed through investment.

Historic England as Echo

At crucial points Dunn invoked his former employer. The Historic England consultation of 7 October 2024—identifying only “a low level of less-than-substantial harm” and praising “opportunities to enliven this part of the conservation area”— was quoted as validation. The public body’s language of opportunity re-emerged as the consultant’s defence, completing a perfect circuit of approval.

The once-regulatory voice of heritage had become the developer’s chorus. As Mills might note, this was not corruption but structure: the migration of conscience into contract, the fusion of public trust with private rationale.

Deliberate Neglect and Convenient Innocence

Under questioning, Dunn dismissed suggestions of deliberate neglect at the Brewery: he had “seen no evidence” that buildings were allowed to decay to ease consent. The denial was procedural rather than factual—the very absence of inquiry serving as proof of innocence. Within that loop, neglect vanishes as a category; only “enhancement” remains measurable. Such logic exemplifies what Mills called “responsibility without consequence”—the moral vacancy at the centre of bureaucratic reason.

The Model of Assurance

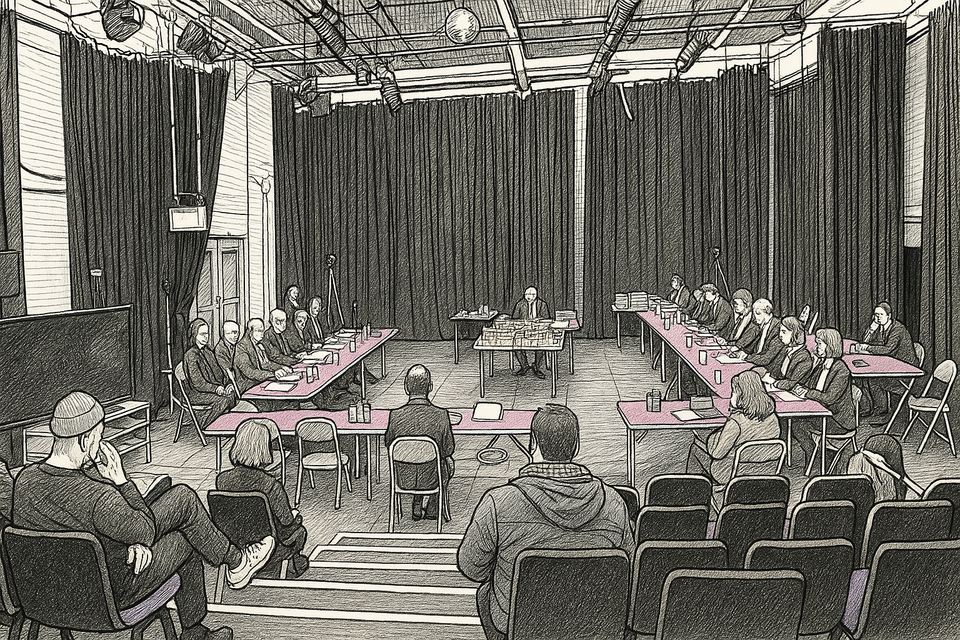

When the final question ended, the solicitor’s binder closed and the scale model of the Truman Brewery was rolled to the centre of the room. Under Harris’s invitation, Dunn stood and walked around it. He traced the perimeter with a hand, nodding toward the neat geometry of towers and courtyards. He offered no new evidence—only confirmation: the physical manifestation of what had already been asserted on paper.

It was a quiet tableau of closure. The expert, once the supposed examiner of truth, had become its custodian of certainty. The model gleamed beneath the hall lights, a miniature consensus. Heritage, now recast in plastic and foam, appeared perfectly compliant.

The Sociology of Certainty

What unfolded that morning was more than a legal exercise. It was the visible mechanism by which technical authority merges with administrative power. Knowledge became choreography; independence, a performance. Each participant occupied a role in a pre-written order where the outcome preceded the argument.

In C. Wright Mills’s terms, this was the “drift of institutions” laid bare, the transformation of democratic scrutiny into managerial ritual. The hearing did not decide whether the scheme was right; it demonstrated that it had already been decided.

Coda: The Circle Closes

As Dunn stepped back from the model, Harris thanked him. The Inspector made a note; the audience exhaled. For a moment, the room held the stillness of agreement—the illusion that every question had found its answer. Outside, Brick Lane carried on: traders unpacking stalls, the air dense with the smell of bread and smoke. Inside, a different kind of labour had taken place—the manufacture of legitimacy.

The architecture of justification had completed its circle, its materials not brick or steel but the language of consent.

About the Thinkers & Further Reading

This series draws from a tradition of writers who treated cities not as neutral landscapes but as moral and political texts.

C. Wright Mills, in The Power Elite (1956) and The Sociological Imagination (1959), exposed how expertise and administration fuse into authority, transforming democracy into a managed consensus. His question—who decides, and in whose name?—echoes through every planning chamber.

Jane Jacobs, in The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961), defended the granular intelligence of streets and communities against the abstractions of professional planning.

Lewis Mumford, whose The City in History (1961) traced the evolution of urban form from temple to metropolis, warned that the metropolis risks becoming a “money-making machine divorced from the needs of life.”

Anna Minton, in Ground Control (2012), revealed how “regeneration” became a euphemism for displacement, while Nicholas Shaxson, in Treasure Islands (2011), exposed how the architecture of finance shapes the built environment as surely as concrete or steel.

Together, they remind us that planning is never merely technical—it is ethical, political, and profoundly human.

Further Reading

- C. Wright Mills – The Power Elite (1956); The Sociological Imagination (1959)

- Jane Jacobs – The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961)

- Lewis Mumford – The City in History (1961)

- Anna Minton – Ground Control: Fear and Happiness in the Twenty-First-Century City (2012)

- Nicholas Shaxson – Treasure Islands: Tax Havens and the Men Who Stole the World (2011)

Editorial note: This report is a fair and accurate account of open proceedings at the Truman Brewery Public Inquiry and is protected by qualified privilege under Schedule 1 of the Defamation Act 1996; commentary reflects the author’s analysis in line with NUJ and IPSO standards.