Day 2 – Heritage and the Moral Script of Regeneration

If Day 1 exposed the financial grammar of regeneration, Day 2 translated it into a moral dialect — the conversion of private interest into public virtue through the language of heritage.

Prologue — Legitimation in Session

At 9:30 a.m. the microphones flickered on again in Southwark Town Hall’s glass-walled extension. The geometry of Day 1 remained — ownership nearest the Inspector, governance to the immediate left, community on the far side — but its function had shifted. Where Day 1 had quantified value, Day 2 qualified it — the language of care applied to the same calculus of extraction. What followed was not neutral procedure but a performance of legitimation — the transformation of private interest into civic virtue through heritage discourse.

Every citation was located by page and bundle number. The central screen behind Inspector Martin Shrigley displayed a frozen image; authority resided in documentation, not display.

Act I — Mr Bevan and the Measure of Harm

Cross-Examination by Russell Harris KC

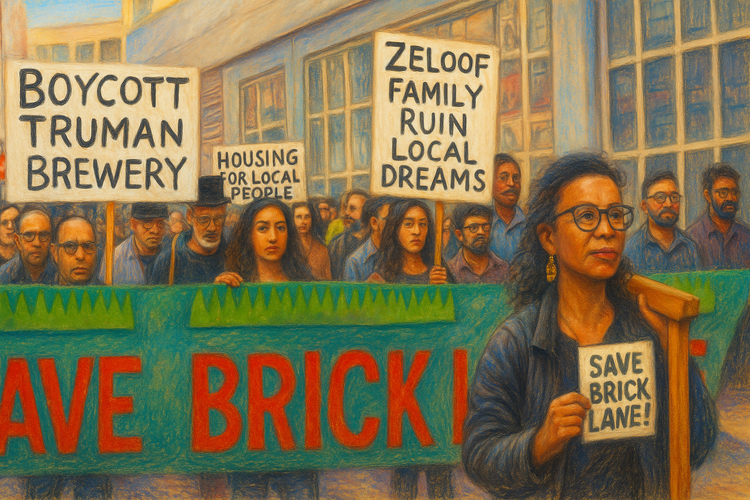

The morning opened with Robert Bevan, the Council’s heritage witness, seated with his Key Images bundle. Before Richard Turney KC could lead him, Russell Harris KC for Berkeley Homes began cross-examination — a choreography familiar from Brick Lane.

Harris: “Would you accept that the existing building does little to enhance the conservation area?”

Bevan: “Yes — but its modest scale does not dominate it. Replacement is not automatically repair.”

Each question sought to turn demolition into duty. The exchange embodied what David Harvey in The Urbanization of Capital (1985) called capitalism’s dialectic of creative destruction — renewal as ruin, civic improvement as alibi for accumulation.

When Turney KC re-examined, he asked:

Turney: “Is harm less real because it is predictable?”

Bevan: “No. Predictability is what makes it structural.”

From the back row Hashi Mohamed for Aylesham Community Action (ACA) asked whether community heritage values were considered.

Bevan: “Not formally — though perhaps it should.”

Inspector Shrigley: “Let’s distinguish visual prominence from heritage significance.”

The remark sounded procedural but performed neutrality itself — the Inquiry’s own grammar of authority.

Interlude — The Neutrality of Authority: Historic England and the Manufacture of Consent

Every inquiry summons Historic England as guarantor of objectivity. Its letters of advice are treated as quasi-legal, yet they function as a civil service of legitimacy — translating policy into reassurance.

At both the Truman Brewery and Aylesham Centre, the pattern was the same: constructive engagement, no objection, tacit assent. An objection withheld becomes endorsement granted. Following David Harvey and Sharon Zukin, neoliberal governance relies on bodies that appear impartial while mediating capital’s advance.

Historic England thus exemplifies this condition — a public institution recast as procedural filter, where the value of place is weighed not by the right to remain but by the acceptable quantum of harm. Its neutrality performs the same task that “design sensitivity” performs for developers: converting the politics of removal into a question of tone. Conditional acquiescence makes demolition appear benevolent. Historic England becomes the ideological interface between heritage and finance — its function not to resist change but to narrate its acceptability.

Heritage and the Framework of Guidance

Debate revolved around a library of reference: Conservation Principles (2008); Good Practice Advice Notes 2 and 3 (2015–17); Advice Notes 1, 4 and 7 (2019–22); and the Rye Lane Conservation Area Appraisal (2016). Together they prescribe a sequence — understand significance, assess change, minimise harm.

Yet at Aylesham those texts were read in reverse. Berkeley Homes cited them to justify “less-than-substantial harm,” permitting approval when “public benefits outweigh damage.” Southwark Council invoked the same lines to insist that Rye Lane was “inherently unsuitable for tall buildings.” Between them, the language of protection bent until it described both preservation and erasure.

The decisive absence was Historic England’s silence: its one-page letter of 7 October 2024 — “comments, no objection.” Objectors read aloud from GPA 3 (Setting of Heritage Assets) and HEAN 4 (Tall Buildings), contrasting their five-step tests with that cursory note. The result was procedural compliance without conviction: every citation met the letter of guidance while dissolving its spirit.

Act II — Claire Hegarty and the Heritage of Continuity

(Aylesham Community Action’s Heritage Evidence)

If Bevan’s testimony defined harm in architectural terms, Claire Hegarty, appearing as heritage witness for Aylesham Community Action, reframed it in social ones. Led by Hashi Mohamed, she offered a reading of Peckham that neither the Council nor the developer had articulated — heritage not as façade, materiality, or height, but as continuity through use.

Hegarty began by situating ACA within Peckham’s own civic history. She traced its lineage to the Peckham Townscape Heritage Initiative and the Peckham Heritage Regeneration Partnership, community-led programmes that restored shopfronts and revitalised the local economy over the last decade:

“The character of Peckham is not merely architectural. It is a combination of tangible and intangible life — its traders, its global-majority communities, its creative scene.”

Her emphasis was unambiguous: heritage is lived time, not inherited form. Against Berkeley’s language of “grain” and “layered façades,” Hegarty argued that Peckham’s distinctiveness lies in the networks that sustain the place, not in the stylistic cues used to mimic it.

“These are not things to be represented in brickwork but to be sustained through policy.”

She extended the Council’s list of harms, noting that the development’s massing — particularly Blocks D, E, G, J1, M, K and P — would erode the very conditions that allow Peckham’s cultural ecosystem to survive:

- affordability for independent traders

- the permeability of the historic laneway system

- the coexistence of migrant economies and creative industries

- the civic memory embedded in long-standing commercial uses

Her intervention shifted the Inquiry’s tone. If Bevan described harm to fabric, Hegarty described harm to relation — a distinction later echoed by Doreen Massey’s spatial theory. Where the developer’s case relied on aesthetic simulation, Hegarty insisted on structural continuity:

“The heritage of Peckham is its relational life. Without the people, the place collapses.”

Her cross-examination was brief but pointed. Asked whether her critique amounted to opposition to development, she replied:

“We welcome change. But it must be change that sustains what is already here, not overwrites it.”

In the chamber, her evidence felt like a counterweight to the technocratic structure of the day — a reminder that heritage is not merely an architectural inheritance but a collective practice, reproduced daily by those who inhabit and sustain the neighbourhood.

Hegarty became the hinge between the morning’s forensic analysis of harm and the afternoon’s aesthetic claims of sensitivity. She set the stage for Act III by posing the question the architecture alone could not answer: What is being layered, and what is being removed?

Act III — Ms Stichtenoth and the Design of Virtue

After lunch, Judith Stichtenoth, lead architect for Berkeley Homes, introduced her proof titled Repairing the Grain.

“We are repairing the grain of Rye Lane through a series of layered façades reflecting its heritage and diversity.”

Her phrasing was devotional — harm recast as healing, demolition renamed repair.

Turney KC pressed:

“Is it really heritage-led if the heritage assessment followed the design?”

Stichtenoth: “It’s a shorthand for sensitivity rather than chronology.” From the back table Hashi Mohamed for ACA replied:

“You say it re-interprets; we say it overwrites.”

Behind the rhetoric of sensitivity lay the same economic compulsion that Day 3 will quantify — capital cleansing the ground to claim renewal.

Theory in Context — The Moral Economy of Demolition

David Harvey describes capitalism’s “dialectic of creative destruction” (The Urbanization of Capital, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1985) as the recurring cycle in which cities are remade to absorb surplus capital — demolition as a structural necessity for accumulation. Renewal, in this sense, depends upon erasure: social and material life cleared to make room for new rounds of investment.

Sharon Zukin, in Landscapes of Power: From Detroit to Disney World (University of California Press, 1991), traced how culture and heritage serve as moral alibis for this process. Through design language, heritage is re-coded as a sign of care; urban transformation is narrated as stewardship rather than displacement.

Day 2 of the Aylesham Inquiry revealed this mechanism in operation. “Heritage-led design” provided the ethical vocabulary through which destruction was reframed as sensitivity. The rhetoric of care gives capitalism its conscience, allowing extraction to appear as renewal — the moral economy of demolition rendered as civic virtue.

The Rhetoric of Layering

Day 2’s governing motif — layering — became metaphor for the whole process, each party using it to define a different order of reality.

For Bevan, layering meant the accumulation of lived time — a palimpsest of working-class presence and everyday commerce embedded in Rye Lane’s irregular urban fabric.

For Claire Hegarty, appearing as heritage witness for ACA and led by Hashi Mohamed, it described continuity through use rather than style.

She spoke of “tangible and intangible heritage — people, traders, global-majority culture, creative energy,” insisting these were “not to be represented in brickwork but sustained through policy.”

Her testimony traced a civic lineage from the Peckham Townscape Heritage Initiative to the present campaign, noting that communities who once restored the area now face displacement by the very value they created. For Hegarty, heritage was the social contract of place — renewal without removal, repair without erasure.

For Stichtenoth, layering became aesthetic composition — brick hues and vertical rhythms arranged to simulate continuity. Her façades performed empathy as design language.

For Inspector Shrigley, layering functioned as method — evidence stacked upon evidence until consensus appeared to form. It was planning’s epistemology in miniature: accumulation mistaken for truth.

As Brett Christophers observes, this is the moral infrastructure of rentier capitalism — the ability to present displacement as care. Each layer conceals the one beneath, manufacturing continuity as illusion. Hegarty’s reminder that “the fabric is not just built form but social practice” hung unresolved as the day closed. What began as a metaphor for heritage ended as a diagram of power — lived history flattened into décor, community translated into texture, sensitivity re-branded as virtue.

Aesthetics as Legitimacy

What Day 1 revealed economically, Day 2 performed culturally. Heritage became the language through which extraction was moralised; design, the conscience of capital.

Across the afternoon session, “good design” was invoked with near-liturgical regularity — as though form itself could redeem process. Where viability had measured worth in percentage points, design now translated those calculations into moral comfort. The vocabulary of architecture — grain, rhythm, layering, sensitivity — became the vernacular of virtue, repackaging commercial logic as aesthetic empathy.

Bevan: “Good design cannot compensate for loss.”

His words landed like dissent in a chamber of reassurance. The line crystallised a paradox visible throughout the Inquiry: beauty used as mitigation, form as justification, loss reframed as progress. In this conversion of harm into harmony, design became a language of authority — the point where economics and ethics converged into image.

By adjournment, neutrality had completed its work. Harm had been translated into sensitivity; sensitivity into virtue. The hearing closed not with resolution but with an atmosphere of aesthetic calm — the architecture of consensus holding firm even as the substance of community slipped away.

Post-Script — Turning Heritage Inside Out

What unfolded in Peckham mirrors what sociologist Loïc Wacquant describes as territorial stigmatisation — the process through which working-class or racialised neighbourhoods are recast as zones of decline or deficiency in order to legitimise their “renewal.” Once a place is marked as problematic, its demolition can be framed as necessary, even virtuous. Heritage, when re-coded as an aesthetic surface, becomes the moral solvent of this process: it dignifies removal under the guise of sensitivity.

The Inquiry also echoed the insights of geographer Doreen Massey, whose work insists that space is not a neutral backdrop but “a product of interrelations, always under construction” (For Space, 2005). For Massey, a place like Peckham is not merely a collection of buildings but a living geography of social ties, histories, and shared practices. To sever those relations — by pricing out traders, erasing small shops, and replacing social economies with investment platforms — is not simply to change a site. It is to unmake a world.

Seen through Massey’s lens, Aylesham was not a debate about design quality or urban form but about what kinds of relations will be allowed to persist. If regeneration rebuilds the physical environment while dissolving the human and economic networks that gave Peckham its meaning, then the city may be renewed, but the place is lost.

Together, Wacquant and Massey illuminate a deeper pattern. Territorial stigmatisation provides the justification; heritage language supplies the virtue; and the erasure of relational life becomes the price of “improvement.”

This is the grammar through which regeneration turns itself inside out — from care into clearance, from preservation into displacement.

Theory in Context — Stigma, Space, and the Politics of Removal

1. Loïc Wacquant — Territorial Stigmatisation

Sociologist Loïc Wacquant argues that disadvantaged urban districts are often recoded as problem places — zones of disorder, deficiency, or decline (Urban Outcasts, 2008). This territorial stigmatisation is not descriptive but strategic: once a place is cast as pathological, its transformation or demolition can be justified as moral necessity.

At Aylesham, this logic surfaced in repeated references to the mall’s “dead-eyed façade,” “failure of grain,” and “under-performance” — diagnoses that frame demolition not as disruption but as cure. Heritage, when reduced to façade language, becomes the ethical solvent of this process: it softens the violence of removal by narrating it as care.

2. Doreen Massey — Space as Social Relation

Geographer Doreen Massey insists that space is not a container, but “a product of interrelations, always under construction” (For Space, 2005). Places like Peckham are not simply buildings; they are living geographies of connection: traders, congregations, family networks, community economies.

To erase those relations through displacement is not simply to “change” an area — it is to unmake the social world that gives it meaning. If regeneration rebuilds the physical environment while dissolving the human networks that sustained Peckham’s identity, then the city may be renewed, but the place is destroyed.

Coda — Setting the Stage for Day 3

As the hearing room emptied, the day had left behind two deeper truths. The first was Wacquant’s: that places like Peckham are remade only after they are recoded as failures. The mall’s “dead-eyed façade,” its “failure of grain,” its “under-performance” — these were not neutral descriptions but techniques of territorial stigmatisation, preparing the ground for removal by defining the existing life as already lost.

The second was Massey’s: that space is not a backdrop for development but “a product of interrelations.” To erase those relations — traders, congregations, family networks, migrant economies — is not simply to change a site. It is to unmake a world.

Day 3 will make the final conversion explicit — the point at which virtue is priced, care becomes cost, and the value of belonging is translated into yield. Destruction authorised by heritage, justified by design, and accounted for by viability: the full circuitry of London’s new planning cosmology.

Editorial Note

This report is a fair and accurate account of open proceedings at the Aylesham Centre Public Inquiry (Day 2 – Heritage and Design Evidence) and is protected by qualified privilege under Schedule 1 of the Defamation Act 1996. Commentary and interpretation reflect the author’s analysis, written in accordance with NUJ and IPSO standards for fair, accurate, and responsible public-interest reporting. Quotations are drawn from the official transcript and submitted Inquiry documents and are reproduced within the context of fair reporting and public record.

Sources and Further Reading

Aalbers, M. B. (2016) The Financialization of Housing: A Political Economy Approach. London: Routledge.

Christophers, B. (2020) Rentier Capitalism: Who Owns the Economy, and Who Pays for It? London: Verso.

Christophers, B. (2023) Our Lives in Their Portfolios: Why Asset Managers Own the World. London: Verso.

Harvey, D. (1985) The Urbanization of Capital: Studies in the History and Theory of Capitalist Urbanization. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Harvey, D. (2005) A Brief History of Neoliberalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Massey, D. (2005) For Space. London: SAGE Publications.

Minton, A. (2009) Ground Control: Fear and Happiness in the Twenty-First-Century City. London: Penguin.

Standing, G. (2016) The Corruption of Capitalism: Why Rentiers Thrive and Work Does Not Pay. London: Biteback Publishing.

Wacquant, L. (2008) Urban Outcasts: A Comparative Sociology of Advanced Marginality. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Wright, E. O. (1985) Classes. London: Verso.

Wright, E. O. (2010) Envisioning Real Utopias. London: Verso.

Zukin, S. (1991) Landscapes of Power: From Detroit to Disney World. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Policy and Guidance Documents

Historic England (2008) Conservation Principles: Policies and Guidance for the Sustainable Management of the Historic Environment. London: Historic England.

Historic England (2015) Good Practice Advice Note 2: Managing Significance in Decision-Taking in the Historic Environment. London: Historic England.

Historic England (2017) Good Practice Advice Note 3: The Setting of Heritage Assets. London: Historic England.

Historic England (2019–2022) Historic Environment Advice Notes 1, 4 & 7: Statements of Heritage Significance; Tall Buildings; Local Heritage Listing. London: Historic England.

London Borough of Southwark (2016) Rye Lane Conservation Area Appraisal. London: Southwark Council.

Suggested Contextual Reading (for subsequent articles)

Christophers, B. (2019) The New Enclosure: The Appropriation of Public Land in Neoliberal Britain. London: Verso.

Harvey, D. (2012) Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution. London: Verso.

Massey, D., Allen, J. and Pile, S. (eds) (1999) City Worlds. London: Routledge.

Zukin, S. (2010) Naked City: The Death and Life of Authentic Urban Places. Oxford: Oxford University Press.