Brick Lane, Rendered Legible to Capital

This essay draws together two strands of ConserveConnect.News work: our day-by-day reporting on the Truman Brewery / Brick Lane Public Inquiry (Tower Hamlets, 2025), and our connected “Asset State” essays on the emerging New London Plan. Its theme is simple: this is not mainly a design dispute, but a dispute about power — about how a redevelopment appeal is won, not only through drawings and policy citations, but through a repeatable logic that converts a lived place into an investable object, and then baptises that conversion as “need,” “delivery,” and “good growth.”

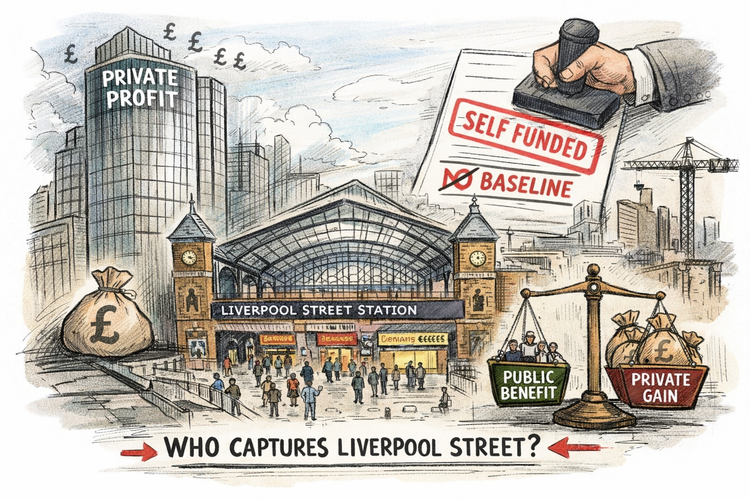

The Inquiry — like the Plan it sits beneath — does not merely test one proposal. It tests a governing paradigm. In the vocabulary developed in the “Asset State” sequence, London’s planning system has been retooled into pipeline management: the logistical movement of investment through land, aided by a language that makes private accumulation sound like public virtue. “Delivery” and “viability” present themselves as neutral terms. In practice they function as moral cover: the claim that the public interest must fit inside the margin.

Seen in that light, Brick Lane is not an outlier. It is a case study — an unusually concentrated demonstration of a machine now operating across the capital. The scheme is introduced as renewal; what is really at stake is ownership of the future: who gets to remain, who gets priced out, and which forms of life the system permits to count as “public benefit.”

The series sequence

The articles in this series form a chain of argument. Each tightens the frame. Each reveals another hinge in the appeal’s logic — another step in the social process by which a neighbourhood is first made legible, then made tradable.

We began away from Brick Lane itself with the three-part “Asset State” sequence, because a public inquiry cannot be understood without the political economy that makes its outcome plausible:

- Part I — The Empire of Finance: How Property Became London’s Primary Market traces London’s long turn from production to property, mapping how governance followed capital into land and housing — and how the city became a substrate of leverage.

- Part II — The Financialisation of London follows, showing how planning and policy are captured by the instruments of finance — viability, opportunity areas, the mythology of “brownfield” salvation — until public standards are treated as conditional on private profitability.

- Part III — London for Sale: An Open Objection to Towards a New London Plan (2025) moves from diagnosis to objection: confronting “deliverability” as ideology, and challenging a housing crisis narrative that treats shortage as natural while treating allocation, hoarding, and power as unspeakable.

With that groundwork in place, the inquiry series commenced:

- Day One — Brick Lane Public Inquiry: Day One Summary laid out the procedural battlefield and the basic asymmetry: an office-led masterplan, minimal housing, and an appeal system capable of outlasting local democratic refusal.

- Day Two — The Grammar of Power tracked the transformation of a contested neighbourhood into an administrable file: counsel, policy language, and expert witness format converting a living place into a case-management object.

- Day Three (Morning) — Landmarks and Blind Spots made the conversion explicit: neglect ripening into leverage; culture translated into yield; numbers and terms functioning as instruments of transfer.

- Day Three (Afternoon) — The Aesthetics of Adequacy turned to reasonableness-by-design: how “adequacy” and “quality” can soften a project’s face while leaving its premises untouched.

- Day Four — The Architecture of Justification examined the justificatory apparatus: Environmental Statement, Design & Access narrative, mitigation cascades — harm reduced to tolerances, protest reduced to technical disagreement.

- Day Five — The Heritage That Matters: Cross-Examining Historic England’s Legacy pressed “heritage-led” claims at their institutional source, revealing how heritage authority can become part of a scheme’s moral packaging.

- Day Five (Afternoon) — Third-Party Submissions: The Wall Still Stands widened the frame: the public record thickening, the narrative tightening — and the same asymmetry of voice and weight reasserting itself.

- Day Six — From Heritage to Humanity marked the endgame: “heritage-led” as slogan, evidence as procedure, planning as performance of reasonableness rather than pursuit of truth.

- Day Seven — From Infrastructure to Inertia: The Question of Need crystallised a key insight: “digital need” functioning as strategy — urgency manufactured while the scope of legitimate urban life is narrowed.

- Day Seven (Afternoon) — The Public Re-Enters the Frame recorded the moment testimony returned planning to its social substrate: a place speaking back to the file that claims to represent it.

- Day Eight (Morning) — Economies of Displacement: Inequality, Legitimacy and the Truman Data Centre made inequality and displacement central — not as accidental by-products, but as structural outcomes of the governing model.

- Day Eight (Afternoon) — Planning as Alibi, Capital as Client named the posture directly: planning as a language of defence for an already-decided outcome.

- Day Nine — Light, Language and the Right to Remain sharpened the technical blade: daylight and amenity metrics functioning as the threshold where lived comfort becomes contestable numbers.

- Day Nine (Afternoon) — Need, Weight and the Test of “Good Growth” tested “good growth” against the record: how need is asserted, weighted, and used to dissolve limits.

- Final Day — Brick Lane on the Scales: Class, Capital and the Financialised City drew the conclusion the system prefers not to state plainly: that this is also a class question — and that the scales are not neutral.

Around the inquiry spine sit three anchor texts that matter because they refuse the premise that “the scheme is the only future”:

- The Truman Brewery Inquiry: When the London Plan Meets the Market Plan sets the confrontation in policy terms: what the London Plan says, what the market requires, and how the latter tries to wear the former as costume.

- Independent Analysis Finds Scheme in Breach of London Planning Law shows the scheme can be contested on its own declared terms — not as taste, but as compliance.

- The Great Housing Betrayal Already Happened in Brick Lane reframes the struggle as continuity: housing and belonging as a single structure, not separate policy silos.

- John Burrell’s Alternative Vision for Brick Lane: Regeneration Without Erasure offers the missing proof: that there are futures beyond campus logic — repair before replacement; livelihood before “activation”; community before marketing.

That is the sequence. Now we can name what it collectively reveals: the core logic deployed to secure the appeal.

The core logic: how the appeal manufactures necessity

1) Convert a neighbourhood into a spreadsheet — then call the spreadsheet “reality”

The first move is epistemic. It is not to persuade the public, but to translate Brick Lane into a format where the public becomes incidental.

The inquiry record shows how quickly the dispute is pressured into a limited vocabulary: “capacity,” “deliverability,” “pipeline,” “strategic need,” “mitigation,” “balance.” Once the dispute is framed that way, the question who is this for? becomes a secondary matter — something to be managed, not something to decide.

This is not simply about expertise. It is about rule by category. The place becomes a case file; the case file becomes a business case; the business case becomes “the public interest.” The lived city is not denied — it is translated into a unit that can be carried, weighed, and priced.

You can watch this conversion taking shape across the inquiry sequence itself — beginning with Day Two’s grammar and intensifying through Day Four’s justificatory architecture.

2) Treat “delivery” as virtue, and speed as morality

The second move is temporal. If London must build at scale, if the system must be streamlined, if safeguards must be “flexible,” then any brake — heritage, daylight, social infrastructure, community consent — can be cast as irresponsible delay.

But this is not merely rhetorical. It is structural. “Viability” does not simply measure feasibility; it becomes an ethic: public obligations must not endanger private return. Once that ethic is installed, democracy becomes conditional. Rights become negotiable. The community’s claims must fit inside the margin.

This is why planning so often feels like an argument about time — not only construction time, but the time-capacity of communities to resist. Appeals outlast leases, campaigns, volunteer energy, trader security. Delay becomes a weapon; exhaustion becomes a planning tactic.

The background to that moral economy is laid bare in the “Asset State” sequence — especially Part II and Part III.

3) Make the data centre the scheme’s moral shield

Here lies the Truman case’s decisive pivot: the data centre as “infrastructure,” and infrastructure as unanswerable need.

Across Day Seven’s “need” argument and Day Eight’s displacement economy, the pattern becomes clear: “digital necessity” is used to elevate a commercial proposition into something like a quasi-public utility. Once that strategic weight is granted, everything else can be reframed as enabling development: offices, retail, massing, phasing, campus logic.

But the sharper point — the point the inquiry makes visible — is that the infrastructure claim does more than justify a building type. It legitimises the conversion of land into a higher-yield asset structure. A social decision is dressed as a technical necessity. A political choice is presented as inevitability.

And inevitability is the most obedient form of argument: it demands submission without debate.

4) Keep housing small — then keep calling it housing-led

The arithmetic appears early and never leaves: offices first; homes as garnish; affordability constrained. The language of the “housing crisis” becomes a general permission slip.

It does not require that this scheme meaningfully meets housing need; it requires only that the crisis mood stays permanently activated — so developments can claim moral alignment with emergency while delivering marginal outputs.

This contradiction — crisis invoked, crisis barely served — is one reason why When the London Plan Meets the Market Plan matters: it insists on reading the scheme against what it actually produces, not what it claims to symbolise.

And it is why Part III is central: the crisis is not only shortage; it is allocation, withholding, price-gating, and power — scarcity manufactured inside a financialised system.

5) Turn heritage into performance — then call the performance “preservation”

What the inquiry shows — especially across Day Five and Day Six — is that heritage can function as cultural escrow: a veneer of continuity used to unlock a discontinuous economic transformation.

Façade retention. Curated “story.” Streetscape “activation.” Carefully lit brick. A new internal world packaged as authenticity.

These are soft terms that can conceal hard transfers. The neighbourhood’s texture becomes a resource — harvested to raise future rents. The past becomes the collateral for pricing the future.

6) Use consultation as proof of consent — even when the content is unusable

This is the procedural heart of the legitimacy crisis: consultation without power.

The most damning detail is practical. A process can meet formal expectations of availability while undermining the possibility of comprehension. When translated materials become functionally meaningless, procedure becomes a substitute for democracy: the appearance of inclusion used to certify exclusion.

This isn’t a glitch. It is a predictable outcome of a governance model that treats the community as a stakeholder to be managed, not a polity to be obeyed — a point driven home in Day Eight (Morning) and sharpened into a single name in Day Eight (Afternoon).

7) Reduce harm to metrics — then fight over thresholds

Translate lived conditions into a metric regime; argue about compliance margins.

Day Nine shows this with daylight: a lived good transformed into a percentage, a ratio, a threshold — then treated as a question of acceptable sacrifice.

This is not to dismiss technical evidence. It is to notice what happens once human life is forced through technical proxies. Thresholds become battlegrounds; qualitative loss becomes quantitative debate; the right to remain becomes the right to contest a number.

The category does not merely describe the world. It disciplines the world.

8) When challenged, retreat to planning as alibi

By the later sessions, the inquiry reaches a kind of self-awareness: planning presented as neutral arbiter even as its categories have been aligned to the needs of capital.

This is what Planning as Alibi, Capital as Client names without euphemism: a language of balance that disguises asymmetry of stakes. The developer risks reduced margin; the community risks disappearance. Yet both are treated as comparable “impacts,” weighed on the same scales.

What the independent analyses change — and what they do not

One might think a rigorous independent finding — identifying breach or conflict with London planning law — would break the spell. The point of Independent Analysis Finds Scheme in Breach of London Planning Law is precisely to show that the scheme can be contested on its own declared terms.

But the inquiry series also shows why technical critique alone rarely suffices. In an asset-led regime, critique must do more than identify policy tension; it must challenge the priority ordering that financialisation installs: that deliverability outranks deliberation; that “need” is defined in investor-friendly terms; that the public realm is treated as a design output rather than a democratic right.

This is why John Burrell’s alternative vision matters: it refuses the starting premise. It begins with repair, retained markets, cooperative affordability, continuity as success — not as an optional extra.

And it is why The Great Housing Betrayal matters: it insists that cultural continuity and built continuity are not separate questions; they are the same structure seen from two sides. Separate them, and both collapse into décor.

Coda: Brick Lane as the city’s mirror

The Truman Brewery appeal is often narrated as a local fight: traders versus offices, heritage versus height, neighbourhood versus campus. But the longer series makes a harder claim.

Brick Lane is a mirror because it shows London’s political economy with unusual clarity. Financialisation does not only raise prices. It remakes governance — turning planning into pipeline management, consultation into ritual, heritage into performance metrics, infrastructure into a moral shield for asset conversion.

And so the inquiry’s deepest question is not “is the scheme compliant?” It is: what kind of city does compliance now produce?

If the city is still a collective work — made by everybody — then a planning system that cannot protect the everyday makers of a place is not merely failing in policy. It is failing in democracy.

If, instead, the city is treated as a financial asset — where people can stay only while they can afford rising costs set by global capital — then the Truman scheme isn’t exceptional. It’s simply how London now works.

The public re-entered the frame on Day Seven because the frame had been built to exclude them. What happens next — at Brick Lane, and beyond — depends on whether London’s institutions can relearn a truth older than the vocabulary of deliverability:

A city is not an investment pipeline. It is a shared public life. And the right to live it cannot be priced as an “acceptable” loss.

Index of critical theorists referenced

Aalbers, Manuel B. — Housing financialisation; how scarcity can be manufactured through investment logics rather than natural shortage.

Christophers, Brett — Rentier capitalism and asset-manager urbanism; how income streams from land and infrastructure reorganise governance.

Durand, Cédric — Fictitious capital; future claims priced into present power.

Harvey, David — Secondary circuit of capital; spatial fix; accumulation by dispossession as urban method.

Jacobs, Jane — The city as collective work; street life, mixed-use ecology, and democratic urbanism against technocratic clearance.

Mills, C. Wright — Power, motive vocabularies, and the conversion of public issues into technical “problems” with preselected solutions.

Minton, Anna — Regeneration-as-extraction; social cleansing through property-led “renewal.”

Mumford, Lewis — The city as lived civilisation rather than growth machine.

Rolnik, Raquel — The empire of finance; displacement as an administrative and economic process.

Samuel Stein — The real-estate state; planning captured by profitability and developer discipline.

Standing, Guy — Rentier economies; wealth extraction through control of scarce assets.

Wacquant, Loïc — Advanced marginality; territorial stigmatisation; how “neutral” institutions reproduce uneven citizenship.

Zukin, Sharon — Authenticity and commodification; cultural texture harvested as asset and brand.

Editorial Note

This report is a fair and accurate account of open proceedings at the Truman Brewery Public Inquiry. Commentary and interpretation reflect the author’s independent analysis in accordance with NUJ and IPSO standards for accuracy, fairness and responsible journalism. This reporting is protected by qualified privilege under Schedule 1 of the Defamation Act 1996.