Brick Lane Inquiry — Day Two: The Grammar of Power

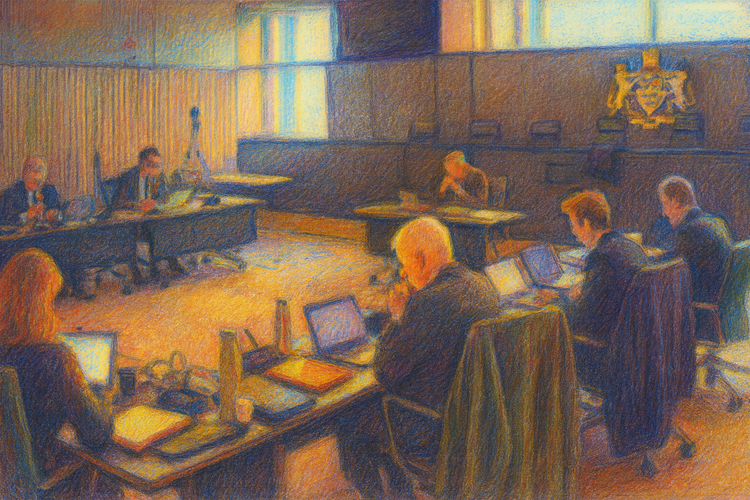

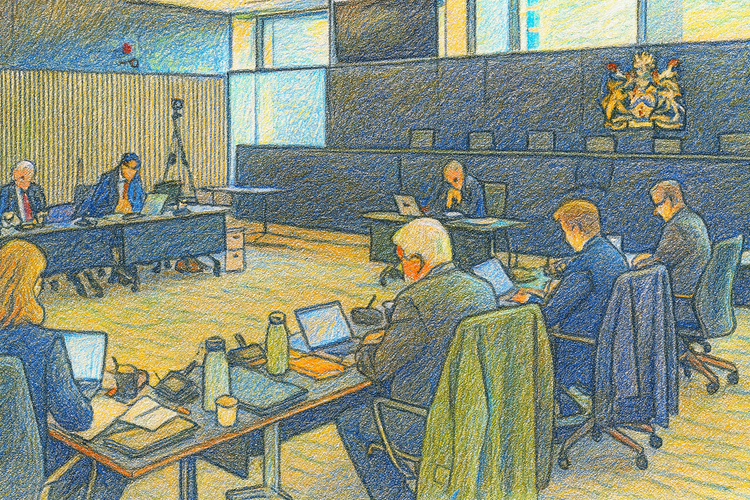

The Setting

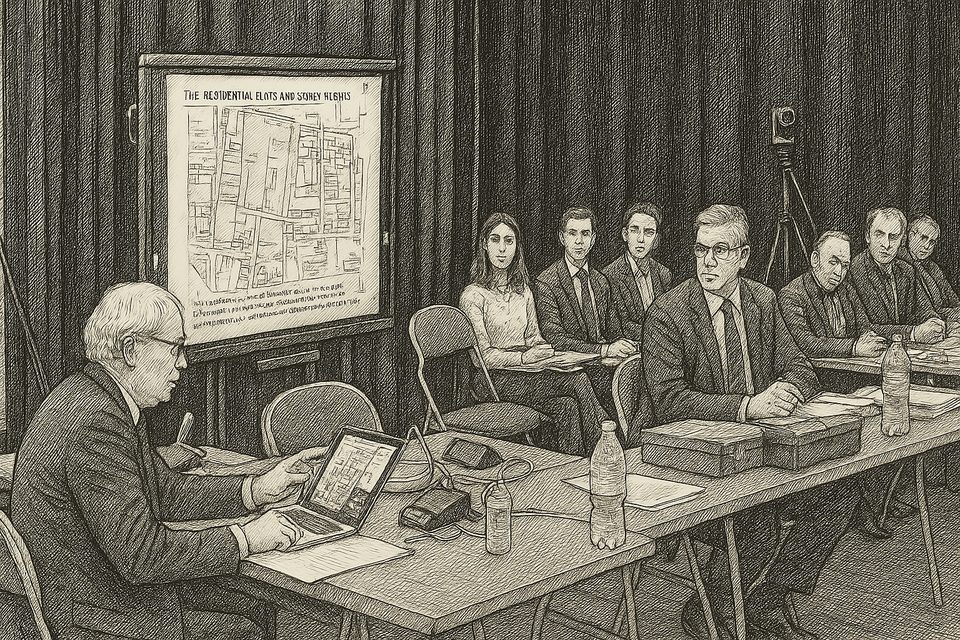

Day Two of the Brick Lane Public Inquiry opened in the stillness of a courtroom repurposed for planning. Architect John Burrell, volunteering for the Save Brick Lane campaign, returned to the witness seat to defend a vision rooted in small-scale repair and civic continuity. Facing him was Russell Harris KC of Landmark Chambers, acting for the developers Truman Estates Ltd and Zeloof LLP. His cross-examination was technically impeccable—and tonally instructive. Each question ended with “Correct?”; each citation of a committee report closed another door of interpretation. Power spoke not through volume but through grammar.

Tone as Strategy

Harris’s method was to narrow the conversation to procedure. Burrell’s architectural language—about permeability, family housing, and “urban repair”—was repeatedly reframed as amateur conjecture. “You haven’t read that, have you?” he asked. “Rule 6 parties have responsibilities.” The Inquiry transcript reads like an aria of interruption: 18 instances of rhetorical containment in under an hour. Burrell remained calm. “We’re volunteers … trying to expand the dialogue,” he said quietly. That modest defence only confirmed the imbalance between a professional advocate and a civic witness.

The Doctrine of Heritage-Led Transformation

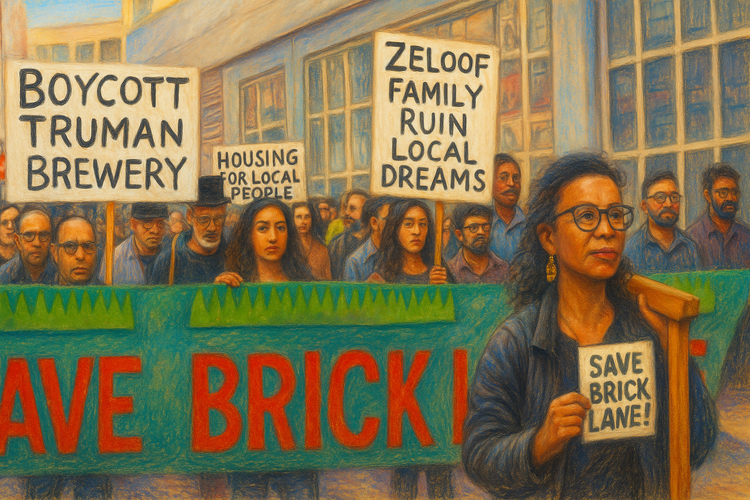

In their published Statements of Case (August 2025), the developers describe the project as a “heritage-led transformation” of the former Truman Brewery—an office-dominated complex presented as cultural renewal. Their own Statement of Common Ground with the Council confirms that all four appeals form “one comprehensive scheme”. Yet in substance, the transformation centres on speculative workspace rather than homes, and on marketable heritage rather than community life. Burrell’s evidence, filed a month later, calls this what it is: a replacement of living heritage with its image.

The Developer as Curator

Planning consultant Jonathan Marginson, appearing for the appellant, portrays the Brewery as a “unique ecosystem” whose commercial reinvention merely continues its historic adaptability. Supporting documents from economic advisers at Volterra Partners and BELCOR recast heritage as market logic: the area is a “micro-market with global demand from creative industries.” In their account, preservation and profitability are synonyms. For Burrell and the Save Brick Lane campaign, that equation is precisely the problem. The rhetoric of “heritage-led” becomes, in practice, “heritage-priced.”

Counterpoint: Continuity and Repair

Burrell’s counter-proposal—family housing above workshops, incremental renewal, permeability over monumentality—aligns closely with the London Borough of Tower Hamlets’ own planning and design witnesses, who warned that the scheme’s bulk “fails to respect the local grain.” His emphasis on people as the measure of scale sits uneasily beside the developer’s spreadsheets of yield and footfall. When Burrell noted that policy must adapt to changing realities, Harris concluded briskly: “Good, thank you for that.” The laughter that followed said the rest.

The Performative Economy

Within the developers’ evidence, cultural vitality is quantified in events: fashion weeks, festivals, pop-ups. These spectacles are advanced as proof of community benefit, even as the underlying tenancy model replaces long-standing independent traders with short-term brands. Economic uplift is substituted for social continuity; culture becomes collateral.

Planning as Rhetoric

Formally, Tower Hamlets continues to defend its refusal of the scheme on the grounds of heritage harm, housing under-delivery, and commercial over-weighting. Yet inside the Inquiry chamber, the linguistic balance favoured the appellants. Legal fluency became the currency of legitimacy. The exchange revealed how easily London’s redevelopment machine converts policy language into authority.

The Ecosystem Myth

The BELCOR market study argues that demand for workspace within the Brewery “exceeds supply” and that expansion is necessary to “protect the local economy.” But the local economy at stake is one of high-value office tenants, not the small workshops and cafés that gave Brick Lane its texture. The estate is not an ecosystem; it is an enclosure under private rent.

Coda: Tone and Truth

As the morning adjourned, Burrell’s restraint stood as its own testimony. The KC’s power was procedural; the architect’s was experiential. One argued for deliverability, the other for belonging. In that contrast lay the Inquiry’s real subject: whether knowledge drawn from community life can survive the professionalisation of planning.

Afterword — The Measure of Inclusion

Beneath the rhetoric of regeneration, the Truman Brewery scheme is overwhelmingly office-led: more than 26,000 square metres of commercial floorspace, just 44 dwellings, and only a handful designated as affordable. No rent controls are proposed, no guarantees for existing traders, no mechanism to prevent speculative escalation.

The economic case advanced by the appellants rests on premium rents and flexible leases for global creative brands—an inversion of the local independence that once defined the site.

What the Inquiry revealed is not merely a dispute over bricks and heights but over definitions of public good. London’s new vernacular of “creative economy” now serves as justification for displacement without compensation.

“Planning is about change and making sure it’s done in the right way,” Harris observed early in the session.

The unspoken question is right for whom—and at what cost to the city’s memory?

Sources & Acknowledgements

This article draws on publicly available inquiry documents submitted by the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, Truman Estates Ltd, Zeloof LLP, and the Save Brick Lane Rule 6 Party, including proofs and rebuttals lodged between June and October 2025.

Editorial note: This report is a fair and accurate account of open proceedings at the Truman Brewery Public Inquiry and is protected by qualified privilege under Schedule 1 of the Defamation Act 1996; commentary reflects the author’s analysis in line with NUJ and IPSO standards..