Brick Lane Inquiry — Day Three (Morning): Landmarks and Blind Spots

By C. J. Carradine

“Every monument hides a balance sheet.” — after David Harvey, Rebel Cities (2012)

Inside the Room

The room was still when Julian Forshaw began to speak. A map of Spitalfields glowed on the monitor, red lines marking conservation boundaries like old wounds. Forshaw, an architect turned heritage advocate, leaned over the diagram as if tracing a scar.

“Spitalfields,” he said, “is one of the most important conservation areas in Britain — a living record of migration and work.” He listed its transformations like a litany: Huguenot silk weavers, Jewish tailors, Bengali restaurateurs. The same bricks had heard three languages of prayer; the same streets, three economies of survival.

Then, looking up at the Inspector, he added quietly: “The proposal freezes the surface and deletes the life beneath it.” The line landed like a verdict.

The Rhetoric of Care

The developer calls its plan heritage-led regeneration. Forshaw called it a contradiction in terms. He spoke of façades cleaned for marketing brochures, courtyards renamed “creative campuses.” “What they call enhancement,” he said, “is re-branding. The chimney becomes a logo; the yards become décor.”

In the hearing’s polite vernacular — “less-than-substantial harm,” “public benefit,” “activation of frontage” — Forshaw heard the language of extraction. He reminded the room that under the National Planning Policy Framework, “historic neglect cannot be used as justification for redevelopment,” then showed how neglect had been allowed to ripen into opportunity. Decay had become leverage.

The arithmetic followed: 26 000 m² of offices, 44 homes, few affordable. A place built by collective labour recast as an address for private tenants.

Conversion of Culture

This was not conservation; it was conversion — the translation of culture into capital, of lived history into yield. The word heritage itself, Forshaw suggested, has been turned from noun to currency.

David Harvey once wrote that every public improvement conceals a transfer of wealth. Here, the transfer is moral as well as material — from the collective to the corporate, from memory to market. Public benefit becomes private gain, measured not in social cohesion but in rental uplift. Every promise of permeability or landscaping conceals an extraction: higher footfall = higher value.

What planning documents describe as “enhancement of setting” is, in Sharon Zukin’s words, a branding strategy masquerading as stewardship. In her studies of SoHo and Brooklyn, Zukin shows how authenticity — the patina of old brick and workshop light — becomes aesthetic capital. Once branded, a district is no longer protected by its heritage; it is owned by it. The Brewery’s red brick, its courtyard clutter, its very irregularity, have been drafted into the developer’s marketing plan. Authenticity has become a design asset.

Then there is “activation of frontage.” In planning jargon it means creating cafés and “vibrant” retail strips to animate façades. But, as Anna Minton observes, activation often means pacification of public space. Security replaces spontaneity; benches give way to branded seating; open access becomes conditional. Brick Lane’s interwoven markets and performances risk being repackaged as “managed vibrancy.” In real-estate language, activation means control.

The Inquiry’s glossary performs ideology. Its vocabulary of care — benefit, enhancement, activation, stewardship — is the soft machinery of dispossession. These words do not describe the city; they produce it. Through them, regeneration becomes a moral act and displacement a by-product of progress. They form the grammar of what Harvey calls accumulation by dispossession — the slow legal reallocation of the commons under the tone of improvement.

Forshaw’s diagrams made the euphemism visible. Each term, rendered in brick and steel, mapped a transfer of ownership. What policy frames as “benefit” is, in practice, the commodification of belonging — a city that performs authenticity while evicting it.

The Meaning of Public Realm

When questioned about the scheme’s network of yards and courtyards, Forshaw agreed that the developer had “missed an opportunity to enhance the public realm.” He said the proposed layout “lures people in and traps them there rather than opening it up as a true bit of public realm.” It was a remark about design, but also about power — how space decides who belongs.

The alternative scheme developed by John Burrell for the Save Brick Lane campaign was cited as offering “regeneration without erasure” — a plan that reused rather than replaced and restored permeability between Brick Lane and Spital Street. Forshaw endorsed it as a design causing “less heritage harm.”

The Vocabulary of Control

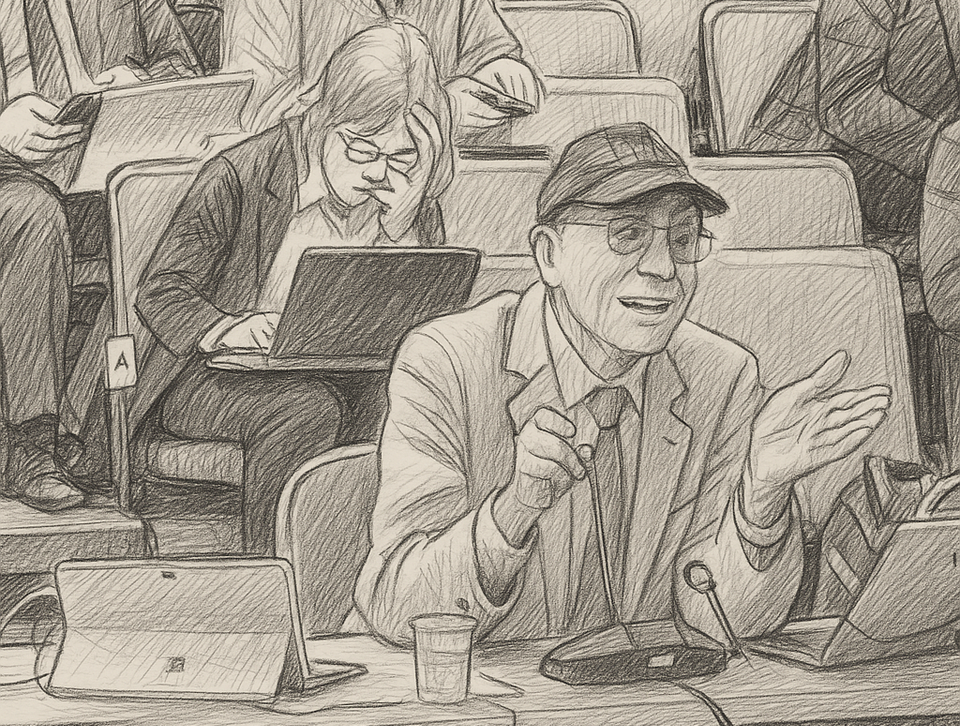

Harris’s cross-examination turned planning terminology into a disciplinary script. Each repeated word — benefit, harm, enhancement, viability — performed what C. Wright Mills would call a “vocabulary of control”: language that transforms moral questions into technical ones. By repetition, Harris framed Forshaw’s evidence within the bureaucratic logic of equivalence — every loss balanced, every meaning priced. “Public benefit,” “enhancement,” “activation.” Each phrase carried the polish of inevitability. To the untrained ear they sounded civic, even generous; but each inverted its meaning.

When Harris asked whether “enhancement of setting” might outweigh harm, he was describing value capture — the revaluation of land through design narrative. When he praised “activation of frontage,” he described private management of space once open. And when he insisted on “public benefits,” the word public referred not to Brick Lane’s residents but to the investor market whose confidence must be secured.

Forshaw’s pauses after these exchanges said as much as his answers. Each question forced him to translate moral judgment into measurable gain; each reply returned meaning to value. It was a duel in the dialect of governance — one side fluent in the metrics of return, the other in the language of belonging. At that moment, the Inquiry became a power conversation: “a politics of decision conducted in the language of expertise.”

Following the Money

Forshaw did not name the investors, but their presence filled the room. Beneath the table of documents lies a chain of Special Purpose Vehicles (SPVs) —corporate shells holding titles, debts and profits. Economists Brett Christophers and Manuel Aalbers call this the architecture of rentier capitalism: profit without production, income without risk. In such structures, heritage is collateral; a listed façade is a guarantee. The past becomes a bond rating. Forshaw’s phrase “neglect as leverage” described the physical symptom of that financial design.

The Frozen Past

Heritage scholars Rodney Harrison and David Lowenthal show how societies freeze history to control meaning. The Brewery’s marketing — all sepia light and “Victorian industrial charm” — performs that freeze. It arrests time to enable substitution: the look of industry without its labour, the smell of beer without its workers. The Council and campaign argue instead for future heritage — heritage as ongoing social production, not fossilised image. In this view, authenticity is not a texture; it is a practice.

Forshaw rejected the notion that heritage was static. “Heritage is a process,” he told the Inspector, “a continuity of use and understanding.” That line, more than any other, summed up the Council’s case: that preservation means maintaining conditions for living history, not displaying it as scenery.

The Commons and the Right to Remain

When Forshaw praised John Burrell’s alternative — “regeneration without erasure” — he aligned it with philosopher Henri Lefebvre’s right to the city: the right of inhabitants to shape and share urban space. Architectural theorist Stavros Stavrides calls this commoning — the social production of space beyond property.

Forshaw’s examples — the curry houses, studios, night markets — described this commons in motion. As designed,“this scheme lures people in and traps them there,” he said. “Ours opens the routes that already exist.” His drawings offered permeability where the developer offered control.

The Global Ledger

Beyond Spitalfields, the logic extends outward. Sociologist Saskia Sassen describes global cities as safe-deposit boxes for capital — heritage cores re-engineered as investment shells. Harvey calls it financial urbanism: the conversion of built history into a yield-bearing asset class. Brick Lane is one more node in that system. Its cobbles provide the aesthetic security speculative money demands. Conservation becomes brand assurance, not civic duty.

The Sociological Imagination

To read the transcript only as planning evidence is to miss its drama. What unfolded in that hall was a parable of modern urban life: the struggle of local memory against global finance. The sociological imagination, Mills wrote, connects biography to history — private troubles to public arrangements. Here the trouble is a street facing erasure; the arrangement, an economy that monetises identity.

Forshaw’s evidence framed the dispute not as one of style, but of stewardship — the obligation to keep faith with the living city. Behind him, the map of Spitalfields glowed red on the screen: a city divided between those who build its image and those who live its reality.

Coda — The Politics of Care

By the close of Day Three’s morning session, the hearing had seen how heritage arguments can carry economic truths. Forshaw’s carefully documented remarks left no doubt that design is never neutral and that preservation is a form of justice. His evidence framed the dispute not as one of style, but of stewardship — the obligation to keep faith with the living city.

About the Thinkers & Further Reading

| Thinker | Key Work / Link | Core Idea |

|---|---|---|

| C. Wright Mills | The Sociological Imagination (1959) / The Power Elite (1956) | Connects personal experience to institutional power; exposes bureaucratic control. |

| David Harvey | Rebel Cities (2012) | “Accumulation by dispossession”: urbanisation as wealth transfer. |

| Sharon Zukin | Naked City (2010) | How authenticity becomes marketing capital. |

| Anna Minton | Ground Control (2012) | The privatisation of British public space. |

| Brett Christophers | Rentier Capitalism (2020) | Profit through ownership, not production. |

| Manuel Aalbers | The Financialization of Housing (2016) | Property as global investment vehicle. |

| Rodney Harrison / David Lowenthal | Heritage: Critical Approaches (2013) / The Past Is a Foreign Country – Revisited (2015) | Heritage as cultural process, not static asset. |

| Henri Lefebvre / Stavros Stavrides | The Production of Space (1991) / Common Space (2016) | The right to the city; urban commoning. |

| Saskia Sassen | Expulsions (2014) | How global capital displaces communities. |

Editorial note: This report is a fair and accurate account of open proceedings at the Truman Brewery Public Inquiry and is protected by qualified privilege under Schedule 1 of the Defamation Act 1996; commentary reflects the author’s analysis in line with NUJ and IPSO standards.