“A Line in the Sand”: Brick Lane Speaks After the Inquiry

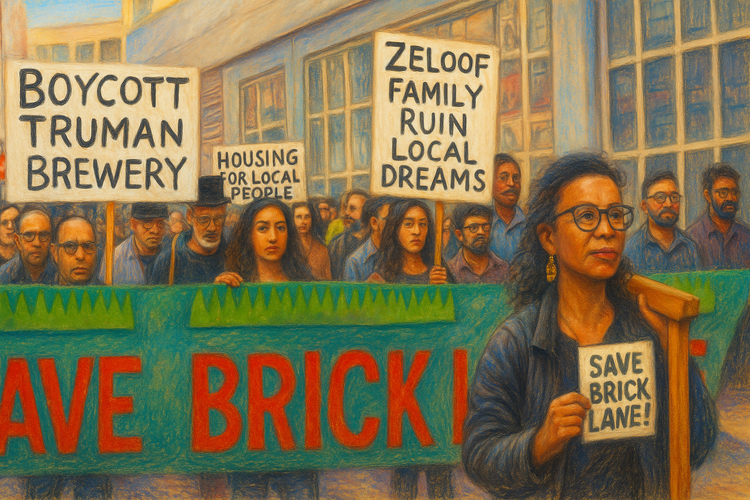

In a modest Whitechapel hall, Save Brick Lane campaigners delivered their post-Inquiry verdict: honour the evidence, repair the harm, and restore democracy to planning.

14 November 2025 — London.

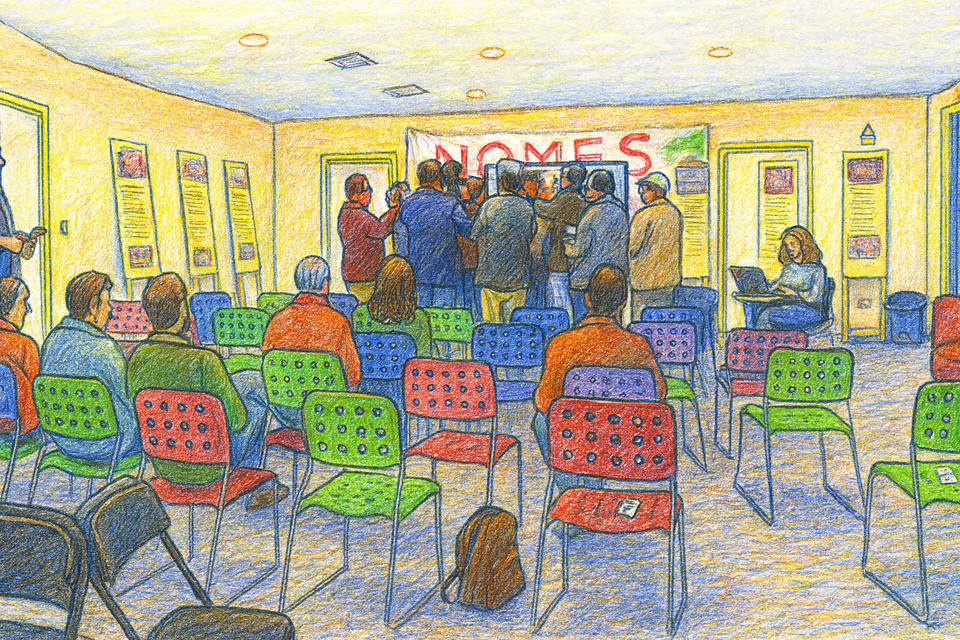

At the Hason Raja Centre in Whitechapel, the chairs were brightly coloured, the carpet still damp from passing rain, and the air thick with questions unresolved. A small panel table stood at the front, backed by posters detailing the long campaign. Between them hung a banner, hand-painted in red: HOMES NOT OFFICES. Campaign materials stood on easels around the room, and media crews clustered with tripods and press equipment at the front.

This was no auditorium or council chamber, no legal theatre or media set. It was a community press conference — raw, direct, and public — organised less than a week after the close of the Truman Brewery Public Inquiry. The room filled steadily with local residents, elders in wool coats and scarves, campaign organisers, Bengali-language media crews, and a handful of quiet observers taking notes. At 2 p.m., the cameras were turned on.

Chaired by former councillor Puru Miah, the press conference brought together key civic witnesses who had given evidence during the Inquiry: Saif Osmani, John Burrell, Charles Glyn, Abdus Shukur, Faisal Ahmed, Abul Khair, Zeba Malik, and Deb Malik. What they presented was not a rerun of the hearings — it was something else entirely: a distillation of the Inquiry’s core findings into a democratic demand.

The Inspector may have closed the record. But in this room, the political record was just beginning to be written.

I. “The future must be determined with the community — not against it.”

Puru Miah opened the event with characteristic clarity:

“The future of Brick Lane must be determined in line with the people’s views — not against them.”

Behind him, the stage was modest — a banner, a screen, a folding table — but the symbolism was unmistakable. This was the same community that had filled the Inquiry chamber for weeks, now gathering to assert its role in the decision-making process. A moment of civic translation: from evidence to argument, from argument to demand.

During the Inquiry, the facts had become impossible to ignore. The Truman Brewery proposal — a commercial-led scheme including a 29-metre data centre, several office blocks and retail units — offers only six social-rent homes on a 10-acre site in one of the most overcrowded boroughs in the country.

Speaking to journalists, Miah summarised what the Inquiry had already established on the record:

- Tower Hamlets has over 28,000 households on its housing waiting list.

- The Truman site is one of the last large plots capable of delivering family-sized, affordable homes in the historic Banglatown area.

- The proposed development, he said, “does not address the urgent housing needs of this borough or respect the role this site could play.”

His remarks echoed what housing researchers and expert witnesses had shown during the Inquiry: that community needs had been sidelined, and policy frameworks were being reinterpreted to legitimise displacement.

II. “Deep plates, deep shadows”: How the Inquiry exposed the scheme

Seated quietly beside the speakers, architect John Burrell listened with his hands folded, a presence more reflective than rhetorical. At the Inquiry, his testimony on Day 2 had established a key theme: the mismatch between the scheme’s spatial logic and the realities of life in Brick Lane. On Friday, he returned to those points — this time not under cross-examination, but as part of a civic forum.

Burrell’s critique, drawn directly from the Inquiry transcript, centred on five core arguments:

1. The floorplates are too deep for future conversion to housing.

“Far too deep to allow for any future residential use,” he told the Inspector. The scheme, in design terms, hardwires in a commercial logic, foreclosing the site’s flexibility over time.

2. The public realm lacks hierarchy or civic coherence.

“No clear square, no boulevard, no civic heart.” The passages are internalised, fragmented, and legible only as an estate plan — not a neighbourhood.

3. The development erases Brick Lane’s historic permeability.

Gone are the minor routes, the interstitial yards, the footpath culture that defines the East End’s human scale. In its place: controlled, managed circulation, unfit for family life or spontaneous encounter.

4. Heritage is used as visual shorthand — a collage, not continuity.

“An image of continuity rather than continuity itself,” he warned.

The motif of memory is present; the substance of heritage is not.

5. His own proposal was never a formal counter-scheme.

Burrell clarified once more what the Inquiry transcript confirms:

“We’re volunteers trying to expand the dialogue — not submitting a rival planning application.” His “alternative” was a sketch — a civic provocation intended to challenge inevitability.

What made Burrell’s contribution so resonant at the press conference was not its policy weight, but its moral clarity: architecture should serve those who live among it, not those who own it from afar.

III. “Whether or not intentional, the effect was discriminatory.”

How the Inquiry heard the equalities case

When Saif Osmani stepped forward to speak, surrounded by lights, microphones, and lenses, the room quieted. His evidence on Day 7 of the Inquiry had delivered one of its most legally consequential arguments: that the consultation process underpinning the Truman Brewery proposal failed to meet even the most basic standards of linguistic and cultural accessibility.

Now, in front of the community, he recounted those findings again — plainly, and without embellishment.

1. The consultation documents in Bangla were mistranslated.

Usmani’s team, working through UCL and in partnership with local organisations, found that:

- Key Bangla-language materials were incomplete,

- Several contained mistranslations that altered or obscured meaning,

- The discrepancies were not merely technical — they resulted in different information being received by different linguistic groups.

2. As a result, Bangladeshi residents were not consulted on equal terms.

As he told the Inspector — and repeated at the press conference:

“Bangladeshi residents did not receive the same information as English-reading residents.”

3. Over 90% of participants in the UCL workshops reported exclusion.

“More than ninety per cent of respondents felt excluded from the consultation process.”

This figure, drawn from the participatory research and recorded under oath, was repeated at the press conference.

4. The effect meets the legal test for indirect discrimination.

“Whether or not intentional, the effect was discriminatory.”

The Planning Inspector did not challenge this legal position. It stands uncontested on the record.

5. The Secretary of State has a legal duty to consider this harm.

Osmani reminded the press that under the Public Sector Equality Duty, decision-makers must:

- Identify any disproportionate impact

- Assess its legal and social significance

- And take remedial steps before any planning approval can lawfully be granted

Community organiser Deb Malik underlined the broader point:

“Bangladeshi and working-class residents were systematically excluded.”

IV. A chorus of testimony, grounded in lived experience

If Osmani provided the legal argument, others offered the social texture — a portrait of life under pressure in a place fighting to remain itself.

- Charles Glyn, former Chair of the Spirit of Field Estate, described a neighbourhood where evictions were no longer an exception, but a cycle.

The proposed scheme, he said, would “accelerate an already fragile process of displacement.”

- Abdus Shukur, speaking as a Trustee of the Tower Hamlets Community Coalition, was measured but firm:

“Homes before offices. People before profit.”

- Faisal Ahmed, whose family has operated a restaurant on Brick Lane for three generations, put it simply:

“We don’t need offices. We need homes.”

- Abul Khair, one of the area’s most respected business figures, warned that every unit handed to corporate retail was a lost chapter in the street’s history.

- Zeba Malik, Vice Chair of the State Standard Association, concluded:

“Thousands have spoken. Their voices must count.”

V. The Inquiry was not halted — but who now holds power?

Some speakers raised questions about the Secretary of State’s “call-in” decision, which places the fate of the development squarely in the hands of central government. While the timing raised eyebrows, the facts remain clear:

- The Inquiry ran its full course, from 12 to 31 October 2025.

- All evidence and cross-examination was completed.

- The Inspector, Paul Griffiths, has closed proceedings and is now drafting his report.

There was no procedural shutdown.

But there was, unmistakably, a shift in power.

Where once the decision would have rested with Tower Hamlets Council, it now rests with a minister in Whitehall.

VI. Brick Lane’s verdict: the moral terms of development

What emerged from the Hason Raja Centre on 14 November was not just a restatement of objection. It was a reassertion of civic legitimacy — and a challenge to the presumption that planning decisions can proceed as though local voices are marginal.

The arguments made were clear:

1. True development requires community consent.

Not consultation as performance. Not postcards in windows. Consent means meaningful participation in shaping the future of place.

2. Equalities are not a procedural box to be ticked.

As the Inquiry revealed, the Bangla-speaking community was effectively denied access to core information about the development. That failure — whether administrative or systemic — has legal implications.

3. Heritage is not aesthetic. It is lived continuity.

Burrell’s critique stands: this is a scheme of simulation, not succession. It borrows the forms of history while hollowing them out.

And so the campaign’s position, repeated by nearly every speaker, became unmistakable:

“This is not anti-development. It is anti-erasure.”

“Brick Lane can change. But not by removing the people who made it.”

The Inspector will deliver his recommendations.

The Secretary of State will decide.

But in the modest hall of the Hason Raja Centre, beneath the banner that read HOMES NOT OFFICES, the message was already settled:

Brick Lane has spoken. And it is watching.